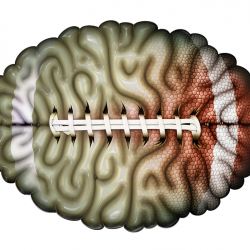

A small, yet promising, brain trauma study may someday lead to a time when doctors can forecast which patients who incurred concussions or repeated blows to the head will be at risk for future neurological problems.

The new study, released this week, has the potential to advance scientists' knowledge of brain injuries and expand the scope of work currently being done to include preventative measures for treating psychiatric issues and onset dementia before they surface. Currently, confirmation of brain damage stemming from concussions, blows and the like, a condition known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, can only be diagnosed post-mortem.

For the study, which was conducted between 2015 and 2016, researchers at Johns Hopkins assembled two groups of men. The first was made up of 14 current and former National Football League players, all of which, according to the study's authors in a release from the medical school, had "a self-reported history of at least one concussion." The second group was comprised of 16 control individuals who were not players, had no concussion history and "were matched to the players by body mass index, age and education level."

All the subjects received a brain scan, called positron emission tomography (PET), as well as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the purposes of monitoring "a marker of injury and repair in the brains of NFL players and athletes in other contact sports."

All the subjects received a brain scan, called positron emission tomography (PET), as well as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the purposes of monitoring "a marker of injury and repair in the brains of NFL players and athletes in other contact sports."

That marker is a substance called translocator protein 18 kDa, or TSPO, which normally exist at low levels in healthy brains. What makes this worthwhile is that because "TSPO is increased during cellular response to brain injury," states the researchers, "high levels of the TSPO signal on each PET scan can indicate where injury and reparative processes occur."

What they found was that the football-playing group had higher levels of TSPO in "in 8 of 12 [brain] regions examined," including the hippocampus, a memory-related area. Moreover, the study's authors wrote in their paper published online in JAMA Neurology, that "limited significant white matter changes were also observed in NFL players compared with control participants, although players and control participants did not differ in regional brain volumes or neuropsychological performance."

"We suspect that when the brain moves during a hard hit, it causes a shearing injury of the white matter fibers that travel across the brain," says Dr. Jennifer Coughlin, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and lead author of the study.

Despite the promising results, no one denies that more research in this area is needed, given the study's limitations, with the small sample size among the issues. Another is that researchers were not able to determine when TSPO levels rose -- over time, or when the head blows occurred -- in the 14 players (four currently in the NFL; 10 retired), who averaged 31 years of age.

"The study showed that there is a measurable degree of this biomarker of brain injury and repair even in young NFL players," Dr. Martin Pomper, a Johns Hopkins researcher said to Reuters, "suggesting that the insult to their brains could have occurred long before they were scanned for the study -- perhaps dating to collegiate or pre-collegiate play."

Lastly, some athletes may have used creatine supplements to improve on-field performance. Researchers readily offer that this might "interfere with the imaging results" and the product may need to be accounted for in future studies.

What's also promising is that future advances in identifying brain damage in living athletes can extend well beyond football and the NFL, and be applied to those exposed to head trauma in all sports as well as other physical endeavors.