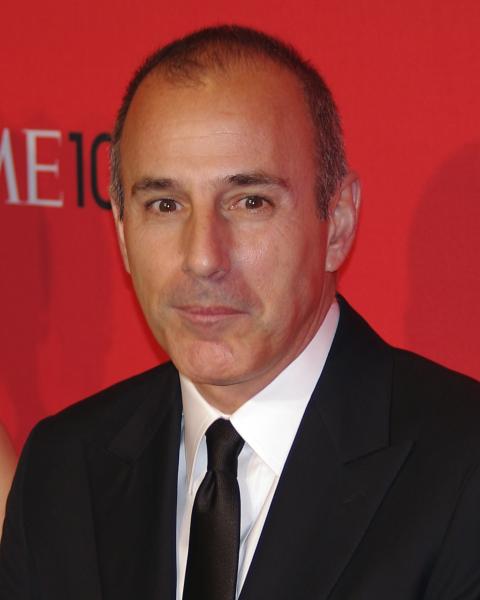

Matt Lauer’s ousting at NBC, due to reports of a sexual harassment scandal, is consuming the internet and media outlets. As such, old clips and stories are resurfacing and being conveyed with an ever suspicious lens.

Among them, is a segment from the now-defunct Meredith Vieira Show where she pokes fun at him for her accidental discovery of a bag of sex toys in his closet. He offered his explanation that Meredith Vieira rebuked, laughter ensues. In the Inside Edition revisit of this find, a sex therapist reveals a private discussion with Matt Lauer that took place at the time.

This raised concerns for me about the basic tenets of doctor-patient privilege.

Self-described on her website as a “world-renowned sex and relationship educator and therapist,” Dr. Laura Berman conveys in part:

“We were in the makeup room, and he sort of asked the makeup artist to leave,” she said. “He asked me about sexual aids and devices. He confided in me about some of the struggles he was having in his married relationship.”

At the conclusion of the piece, the anchor Deborah Norville maintains “Dr. Berman says she was free to speak because Matt Lauer was never a patient of hers.”

But, is that true?

There is the fundamental notion of privacy when one person speaks to another person. At a minimum, even Dr. Berman conveys he cleared the room and “confided” in her, which implies there was a considerable expectation of privacy. Forget for a moment that one party is a health provider, at the core there was a violation of trust and betrayal of confidence. The Inside Edition interview poses an ethical conundrum for a relationship expert.

When does someone become a patient?

For an attorney, the line is clear that as soon as a dollar is exchanged a person becomes a client. In this scenario as it is described, Mr. Lauer took actions to seek out Dr. Berman precisely for her professional expertise in a closed off setting. Had he given her remuneration for the curbside consult would the privilege be more forcibly upheld? For a physician, the line is less clear.

This occurs quite often when out to dinner or in the gym, for instance, that upon discovery of being a doctor a stranger will request advice. General medical information would not obviate such confidentiality. For example, providing explanation when asked about my thoughts on the flu vaccine or vaccinating children. But, regardless, it tends to be the default position of medical professionals anyway given the magnitude of importance placed on the oath to do no harm.

Now, if someone shows me a lump at Christmas dinner and I tell him it is concerning and he should be seen expeditiously, has that met the standard of doctor-patient privilege? As a medical professional it would not even matter, I would follow-up with that person and not discuss the conversation without their consent.

In more urgent, extreme settings, Good Samaritan laws (though variable by state in their protections) take into account the often blurred line of professional versus private person when a situation like intervening with injured strangers after a motor vehicle accident arises.

What makes this Matt Lauer scenario any different?

It is especially important because this type of encounter plays out every day in a variety of ways and indiscriminate disclosure challenges the sanctity of the doctor-patient relationship. If a patient cannot expect such privacy—a concept that prompted the origin of these laws to begin with, then he/she will not seek treatment and could delay important therapies.

Mr. Lauer’s actions to secure the location and seek out help more than imply he believed he was a patient or like a patient. As a physician, I would recognize this and feel compelled to uphold his perceived privacy. Though Dr. Berman is described as a licensed social worker with a PhD in health education, she does list a faculty appointment as an assistant clinical professor of ob-gyn and psychiatry at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. Such an affiliation with a medical school would imply a deeper understanding of the complexities of bioethics and patient-clinician privilege.

When does a doctor stop being a doctor?

Ask anyone who is, and it is hard for them to answer.

Though the line might get more malleable defining the moment someone becomes a patient, we as health providers have a duty to maintain an ethical standard and ensure it remains on solid ground. Confidence in good faith shouldn't be eroded.