Co-payments serve two purposes; first, they offset costs, well actually they add costs to you and reduce them for your insurer who never really "pays" for your care; and second, they make you think twice before you access your care. But drugs are, after all, prescribed for you; they are not necessarily a voluntary purchase, so that second argument about thinking twice is not germane.

Even though you hand your co-payments to a pharmacist, they are not actually receiving them; they are returned to the pharmacy benefits managers (PBMs an oft-mentioned intermediary in drug pricing), the pharmacists receive their negotiated payments (the drug cost, dispensing fees, and any markup) separately - referred to as the national average retail price or NARP [1]. A research letter in JAMA casts light on the differences in your co-payment and what pharmacies actually receive, the NARP.

Since co-payments offset costs, you would expect that your co-payment is less than the pharmacies receives; after all the NARP (you got to love some acronyms) includes the co-payment and the drug cost. You would be very wrong. The researchers compared co-payments to NARPS using a 25% random sample from Optum, a healthcare PBM and data provider. The claims represent nationwide commercial insurance transactions for individuals between 21 and 64 years of age. They looked at 9.5 million claims defining overpayment when your co-payment was 10% greater than the NARP, the money paid to the pharmacy [2].

For brand-name drugs, 6% of co-payments were greater than what pharmacy’s received and for generics that percentage rose to 28%. We are not only paying for the drugs at bust-out retail; we are sending additional money to the PBMs. While “over-charged” co-payments for brand-name drugs occurred less frequently, the overage was more $13.46 (mean value), for generics, the overcharge was $7.32. But those “golden crumbs” add up, $135 million in 2013 or about $10.51 for each of our covered lives.

Evidently, PBMs were prescient, concerned about contributing to the opioid crisis as early as 2013 (the period covering by the data) because the most commonly prescribed drug, hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin) involved overcharges in 36% of claims at almost $7 a pop. In fact, because PBMs have far more information than we do about prescription drugs, 12 of the twenty most common drugs were overcharged more than 33% of the time. [3]

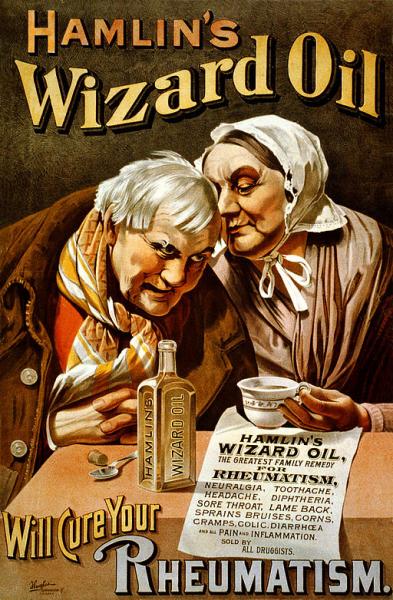

That our co-payments not only fully cover the cost of the drug but provide a little extra to PBMs is a real-world example of why drug pricing needs to be transparent, where you and I know the same information as the drug merchants. If not, as the data clearly demonstrates, they will take advantage of the situation and have us paying full freight while telling us that we are just paying our fair share. It is long past time to be woke, as PT Barnum allegedly said, there’s a beneficiary born every minute.

[1]As discussed previously, any of these aggregate national prices bear scrutiny, but these reflect the amount paid for drug ingredients, dispensing fees and customer copayments reported monthly by retail pharmacies. They are not really controversial.

[2] For co-payments of less than $20, a difference of $2 was considered overpayment.

[3] In addition to pain medications, the medications with overcharges included those for thyroid disease, heart disease, elevated cholesterol, inflammatory diseases, depression, and insomnia.

Source: Frequency and Magnitude of Co-payments Exceeding Prescription Drug Costs JAMA DOI: 10.1001/jama.2018.0102