Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) have been used in the United States since the early 20th century. Prior to 1914, natural opiates—the predecessors to modern synthetic or semi-synthetic “opioids”—were unregulated by the federal government and widely available for purchase without prescription in most of the United States.1 Use among the American public was quite commonplace. According to one article published in The New York Times, one in every 400 United States citizens had some type of opiate addiction by 1911, reportedly due to “the sudden emergence of street heroin abuse as well as iatrogenic [induced by medical treatment] morphine dependence.

In response to rising levels of Chinese immigration to the U.S., which was blamed for rising rates of opium use, states like California began outlawing the recreational consumption of various narcotics. San Francisco became the first U.S. municipality to enforce an anti-narcotics law in 1875, outlawing the operation of opium dens, which became state law in 1881. By 1907, California’s State Board of Pharmacy quietly lobbied for an amendment to the state’s poison laws, which prohibited the sale of opium, morphine, and cocaine except by a doctor’s prescription.

Eventually, the U.S. Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act in 1914, the first federal statute regulating the production and sale of opiates and cocaine, which was enforced as a ban on the recreational sale of both products. Under this law, physicians across the U.S. were also restricted from prescribing opiates to addiction patients, and all proprietors of opium products needed to be registered with the federal government, creating the ancestor to the modern PDMP databases.

In an effort to further combat overprescribing, states slowly began to develop their own monitoring programs, the first of which was created in New York in 1918. However, these early PDMPs were rather slow in their collection speeds and used inefficient paper reports to monitor the prescription history of patients.

These programs developed throughout the mid-20th century and were rather ineffective, as “[p]rescribers were required to report to databases within 30 days, too long a time to reasonably be useful in preventing real-time ‘doctor shopping’ or over-prescribing." Additionally, there were no electronic databases tracking which patients had recently filled opioid prescriptions for doctors to reference.

Given the weaknesses of these early PDMPs, few states adopted any type of monitoring program over the course of the first half of the 20th century. However, the proliferation of PDMPs was greatly enabled by the ruling of Whalen v. Roe in 1977, a case that upheld the constitutionality of New York’s precursor of the PDMP under the broad police power given to the states by the Tenth Amendment. The plaintiffs of this case argued that the monitoring program constituted an invasion of patient privacy, due to its collection and storing of prescribing records. Writing for the majority, Justice John Paul Stevens held that, “[n]either the immediate nor the threatened impact of the patient identification requirement on either the reputation or the independence of patients…suffices to constitute an invasion of any right or liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.” With the constitutionality of patient prescription monitoring upheld, states were able to pursue data collection on prescribing history more thoroughly. Empowered by this ruling, many more states began to operate some form of a PDMP.

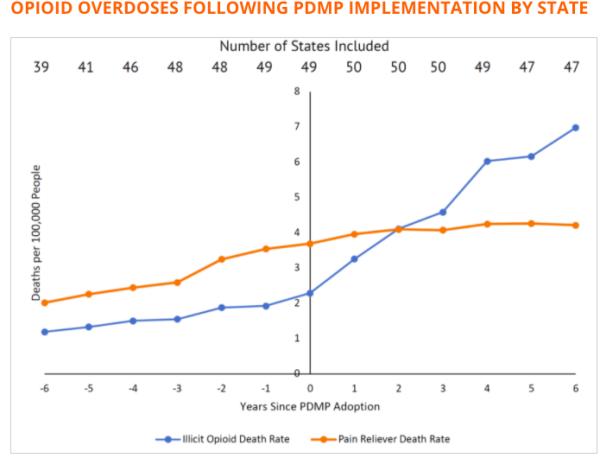

Since Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs fail to achieve their ultimate goal of reducing opioid overdoses, their funding should be re-appropriated to more effective mechanisms to reduce addiction and overdose rates, such as providing access to prescription-quality opioids for medication-assisted treatment.

# This excerpt was reprinted with permission. The 0pinion piece in its entirety can be read here.

Jacob James Rich is a policy analyst at Reason Foundation and a Ph.D. candidate at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine.

Robert Capodilupo is a policy contributor at Reason Foundation and a JD candidate at Yale Law School.