Polypharmacy's grip tightens as we age

89% of adults aged 65 or older take a prescription medication compared to 75% of those aged 50-64. More than half of those older adults, 54%, take four or more prescribed medications compared to a third of those 50-64 year-olds. According to the Lown Institute, 20% of the elderly use ten medications or more, and between  1994 and 2014, the “proportion of older adults taking five or more drugs tripled, from 13.8 percent to 42.4 percent.” While Lown describes the situation as an epidemic of “medication overload,” the term used by clinicians is polypharmacy.

1994 and 2014, the “proportion of older adults taking five or more drugs tripled, from 13.8 percent to 42.4 percent.” While Lown describes the situation as an epidemic of “medication overload,” the term used by clinicians is polypharmacy.

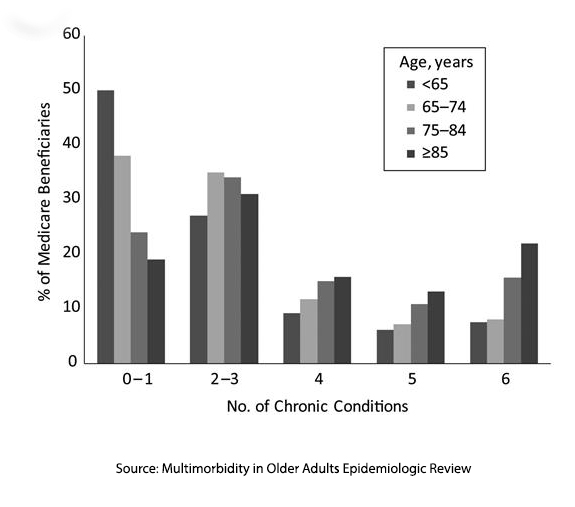

None of this should be surprising. An earlier study in 2008 looking at Medicare beneficiaries demonstrated that the co-morbidities necessitating all of those medications also rose with age. That being said, because of our fragmented health system where multiple physicians are prescribing medications to the same patient (when everyone is responsible, no one is responsible), changing medical status and drug interactions may result in adverse drug effects (ADE).

The Shadow of Adverse Drug Effects

A study from 2016 looked at Emergency Department visits for adverse drug effects. In a sample of roughly 44,000 patients – 4 out of 1000 involved ADEs and about 25% of those resulted in hospitalization. Those rates are higher for those over 65, with 9.7 of 1000 ED visits for ADEs with a hospitalization rate of 43%. The medications that resulted in an ADE for this age group included warfarin (an anticoagulant), insulin, and two drugs used for their anti-platelet activity (clopidogrel and aspirin) [1]

Deprescribing offers a hopeful approach

Countering the rise in polypharmacy and its associated adverse consequences has been an increasing effort to deprescribe medications. Deprescribing is the

“process of medication withdrawal, supervised by a health care professional, with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes.”

Deprescribing focuses on acting before a drug-related ADE occurs and may be especially useful for patients with

- Renal insufficiency making the clearance of some medications problematic

- Medication non-adherence – polypharmacy leads to missed and excess doses

- Limited-lifespan – continuing medications designed to lower risk over 5 years have little value for those with a two-year lifespan

- Dementia or frailty where life goals may have changed since medications were initially prescribed.

Deprescribing has its barriers. The most problematic part is the time spent sitting with the patient and their family to determine what medications are necessary and which might be jettisoned. This problem is made worse when multiple prescribers are involved and

“clinicians may feel like it's not their role to manage the medications (devolving of responsibility) or may not wish to make changes due to professional hierarchies … damaging the patient's relationship with this other professional by providing contradictory advice.”

In a medical culture trained “to do,” there is a relative lack of evidence for the benefits of deprescribing. The end result is that we rarely deprescribe medications. A survey found that only 30% of those most at risk for polypharmacy had a comprehensive medical review by their physician.

Given the barrier of physician time, it was inevitable that Silicon Valley’s latest gift to medicine since the electronic medical record, AI, would be offered as a solution. A test of AI’s ability to deprescribe was reported in the Journal of Medical Systems.

Can AI chart a better path?

ChatGPT 3.5, its public form, trained on “textual sources from websites, articles, books, and more,” was given three clinical scenarios involving a retired 82-year-old man, a retired carpenter with hypertension and chronic back pain, taking seven medications. [2] Each scenario differed in the patient's ability to manage the activities of daily living (ADLs) – from fully independent to needing help with “personal hygiene, getting dressed/undressed and preparing medication,” to needing to use a walk, with some disorientation and an unintended weight loss. An additional variable, a cardiovascular event, i.e., myocardial infarction, within the last three years, brought the total scenarios proffered to ChatGPT to six. ChatGPT was asked whether it would deprescribed medications and which.

“ChatGPT exhibits both willingness to deprescribe excess medications in patients without cardiovascular disease history and caution towards changing medication regimens in patients with a prior cardiac event.”

- The presence or absence of ADL limitations did not impact the AI recommendation to deprescribe, although it increased the number of medications deprescribed from 2.7 to 3.3 as the ADLs worsened.

- When cardiovascular disease was present, AI was more conservative, reducing the number of deprescribed medications.

More telling were the medications deprescribed.

“ChatGPT preferentially deprescribed pain medications as compared to other medication categories regardless of both cardiovascular disease history and ADL status. …this is a concerning finding.”

Indeed, it is. While the researchers felt this might reflect a relative disregard for pain over other medical conditions, I would argue that ChatGPT reflects the frequency of anti-opioid sentiment presented on the Internet, its source of ground truth. In the study’s supplement, it provided ChatGPT’s complete response, this is typical.

“… given that the patient is in good physical and cognitive condition, it may be appropriate to consider tapering or discontinuing the tramadol. Chronic use of opioids is associated with several risks, including physical dependence, tolerance, and adverse effects such as constipation and cognitive impairment.”

The scenario did not indicate in one way or another concerning physical dependence, tolerance, or adverse effects, which reduces the value of AI’s suggestions. At best, it might alert the busy physician to the need to discuss and deprescribe, but it would do little to reduce the real work involved in teasing out the critical patient-specific risks and benefits.

ChatGPT is sufficiently trained to reduce its liability,

“It is important to note that any potential changes to the patient's medication regimen should be made in consultation with the patient and his healthcare team to ensure that any deprescribing is done safely and effectively. The other medications listed …are commonly prescribed for the management of chronic conditions and would require further evaluation before considering any deprescribing or dosage reduction.”

The researchers felt a more focused model would provide greater internal consistency in its recommendations and overcome the bias concerning pain medications. Deprescribing emerges as a promising avenue to reduce polypharmacy, but it's clear that significant physician involvement is crucial to effectively navigate this process. While artificial intelligence (AI) offers a “promise,” balancing technological innovation with human oversight is essential. As Marie Kondo might say, we must find harmony between cutting-edge technology and the human touch in promoting optimal health outcomes.

[1] These numbers should be taken with a grain of salt as warfarin has largely been supplanted by the newer generation of anticoagulants that require less monitoring and have an overall safer profile.

[2] The medications included two pain medications, tramadol and acetaminophen, a proton pump inhibitor (to prevent ulcers), two blood pressure medications for hypertension, a statin, and aspirin.

Sources: Proactive Polypharmacy Management Using Large Language Models: Opportunities to Enhance Geriatric Care Journal of Medical Systems DOI: 10.1007/s10916-024-02058-y

Multimorbidity in Older Adults Epidemiologic Reviews DOI: 10.1093/epirev/mxs009