Intuitively, R&D, accounting for about 20% of drug revenue, would be reduced as profit declines. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that:

“The number of drugs that would be introduced to the U.S. market would be reduced by about 1 over the 2023-2032 period, about 5 over the subsequent decade, and about 7 over the decade after that.”

A more apocryphal study from the University of Chicago CBO anticipated,

A more apocryphal study from the University of Chicago CBO anticipated,

“The cut in new drugs is about 27 times larger than the Congressional Budget Office’s predicted loss of five drugs over the same period.”

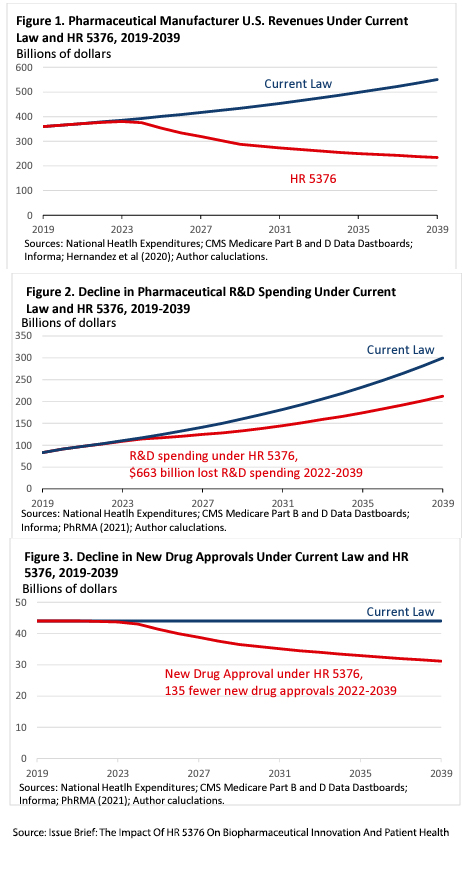

These graphs from their modeling summarize their concerns. The estimate of how R&D spending moves in line with revenue is based on prior observations averaged across ten studies, which suggested that for every one percent decrease in revenue, R&D spending would decrease by 1.54%.

All models are simplifications, and as a result, all models are untrue. Several unfounded assumptions limit the model’s explanatory power at best, primarily because they do not capture the dynamic interplay when the law impacts agile business. What dynamics are left unaccounted for?

Do drug prices and revenue track together?

The short answer is no because of the deliberate opacity of drug pricing and the hidden rent [1] collected by pharmacy benefits management (PBM) companies.

The Federal government pays for drugs through Medicare and Medicaid, with Medicare providing 3-fold more payments. Medicare payments are provided in two “parts.”

Part B payments are for medications used during treatment in physician offices, outpatient, or inpatient facilities. Their pricing is based on the average sales price (ASP), which is perhaps the “trueist” drug price we see, taking into account all the hidden rebates and discounts, the rents collected by PBMs. Under the new federal negotiations, these prices can continue to rise with inflation, so Pharma profit remains constant, and revenue remains solely dependent upon sales.

Part D payments are for drugs we purchase from pharmacies, this accounts for 94% of government Medicare drug spending. In the legislation, a portion of the money the government expends for the Part D drugs will be rebated to the government when increases in the average manufacturers' price (AMP) exceed the inflation rate. AMP is much like a car’s sticker price, and does not consider hidden negotiated rebates and manufacturer discounts. These hidden price reductions are partially passed on to us as lower prices. Yet, a greater percentage is claimed by pharmacy benefits managers (PBMs) and their corporate owners, health insurance companies.

“To avoid triggering inflation rebate penalties, manufacturers will offset most of those reductions [in AMP] by reducing rebates paid to Part D plans.”

- CBO

Manufacturers can maintain their share of revenue for Part D drugs by reducing PBM discounts and rebates. Faced with penalties for raising their prices above that of inflation, manufacturers may more often decide to lessen the PBMs’ share of the pie rather than theirs. This uncouples, or at least modifies, the relationship between drug prices and revenue. Furthermore, it only applies to drugs currently being marketed.

These new pricing limitations will be accounted for as new drugs come to market. They will be set at a higher price point, a decision not impacted by the legislation.

“First-in-class” or “Me-too”

First-in-class medications are drugs with novel actions, what we term innovative.

“These “me-too” drugs have an identical primary mechanism of action to the initial first-in-class drug but are chemically distinct enough to allow for patent protection without patent infringement. Unfortunately, they also possess little potential to improve the efficacy or safety profile of the first-in-class drug.” - Forbes

While Forbes's definition is correct, some me-too drugs reflect significant clinical improvement in terms of ease of use and reduction in unwanted adverse effects. While the underlying cost of bringing a “first-in-class” drug to market is considerably more significant than for a “me-too” drug, economic studies suggest that first-in-class drugs have a 6% greater market share. However, there are many instances where subsequent “me-toos” have dominated. A recent example is Pradaxa, the first-in-class novel anticoagulant, which rapidly began to replace Coumadin because of Pradaxa’s improved safety profile, which reduced major bleeding. Xarelto and Eliquis, the “me-too,” were subsequently approved by the FDA. Xarelto lowered the risk of stroke but had more major bleeds; Eliquis lowered the risk of stroke and major bleeding. In 2022, Eliquis sales, at $18 billion, were more than double that of Xarelto; Pradaxa had $1 billion, and Coumadin’s global sales were $500 million.

As a review of me-too pharmaceuticals in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology reports,

“it is cheaper for a company to launch a me‐too follow‐up drug than to launch the first in class. This may well release R&D money for undertaking more high‐risk breakthrough products.”

So here again, we have another uncoupling of new products from R&D expenditures.

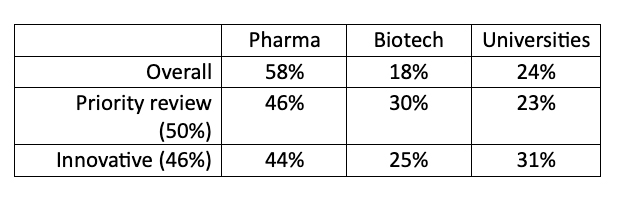

The final simplification is the assumption that innovative drugs come from what we would term Big Pharma. While true several decades ago, the sources of innovation have changed. A review in Nature of all drugs approved by the FDA through 2007 demonstrated that while Pharm was responsible for the majority of new drugs entering the market, both biotech companies and universities were responsible for a larger share of medicines approved by priority review, a proxy for unmet medical need, or were considered innovations.

As Derek Lowe writes, commenting on the study,

“The bigger drug companies are (as you'd expect) evaluating compounds on the basis of their commercial potential, which means what they can add to their existing portfolio.”

Unlike the other sources of new drugs, Big Pharma has a global footprint in sales and navigating the regulatory systems. That is their greatest superpower, and increasingly, over time, they are outsourcing some of their R&D because it is less costly to buy the company or license the technology than to innovate on their own. We need look no further than the number one selling drug in 2022 at just shy of $56 billion, the COVID vaccine released by Pfizer and developed by BioNTech. Biotech firms, like BioNTech, have their paydays when their drug is licensed, or when their company is purchased.

So, will the sky fall on drug innovation just because Medicare is cracking down on prices? Probably not. Arguing that price limitations will reduce innovative drugs because of falling revenues is too simplistic an explanation. Big Pharma's wails about dwindling R&D budgets seem more like strategic hand-wringing than reality. Between nimble biotech startups, university-led breakthroughs, and a robust market for "me-too" drugs, Big Pharma's real gripe isn't about innovation but protecting their bottom line.

[1] Rent is an economic term for payment made or benefit received for non-produced inputs.

Sources: Issue Brief: The Impact Of HR 5376 On Biopharmaceutical Innovation And Patient Health University of Chicago

CBO’s Simulation Model of New Drug Development

The FDA Delivered A Big Win For Innovation Against Foreign “Me-Too” Drug Makers Forbes

Pharma’s first-to-market advantage McKinsey&Company

The importance of new companies for drug discovery: origins of a decade of new drugs Nature Reviews Drug Discovery DOI: 10.1038/nrd3251