Like tens of thousands of Americans baking in the summer heat, last week President Biden was convalescing at home, waiting for the COVID symptoms to pass. It’s that time of year again, in what is likely to become a stressful ritual for many years to come: the summer COVID surge, not unlike the winter outbreak of flu that we've come to expect.

Infection levels have already surpassed last summer’s peak, and are still rising. According to the CDC's most recent update, COVID test positivity, Emergency Department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths were all trending upwards. A primary care physician at a large healthcare provider in Northern California told me last week that he was seeing dozens of new cases of COVID a week and that test positivity was over 50%, which is unprecedented.

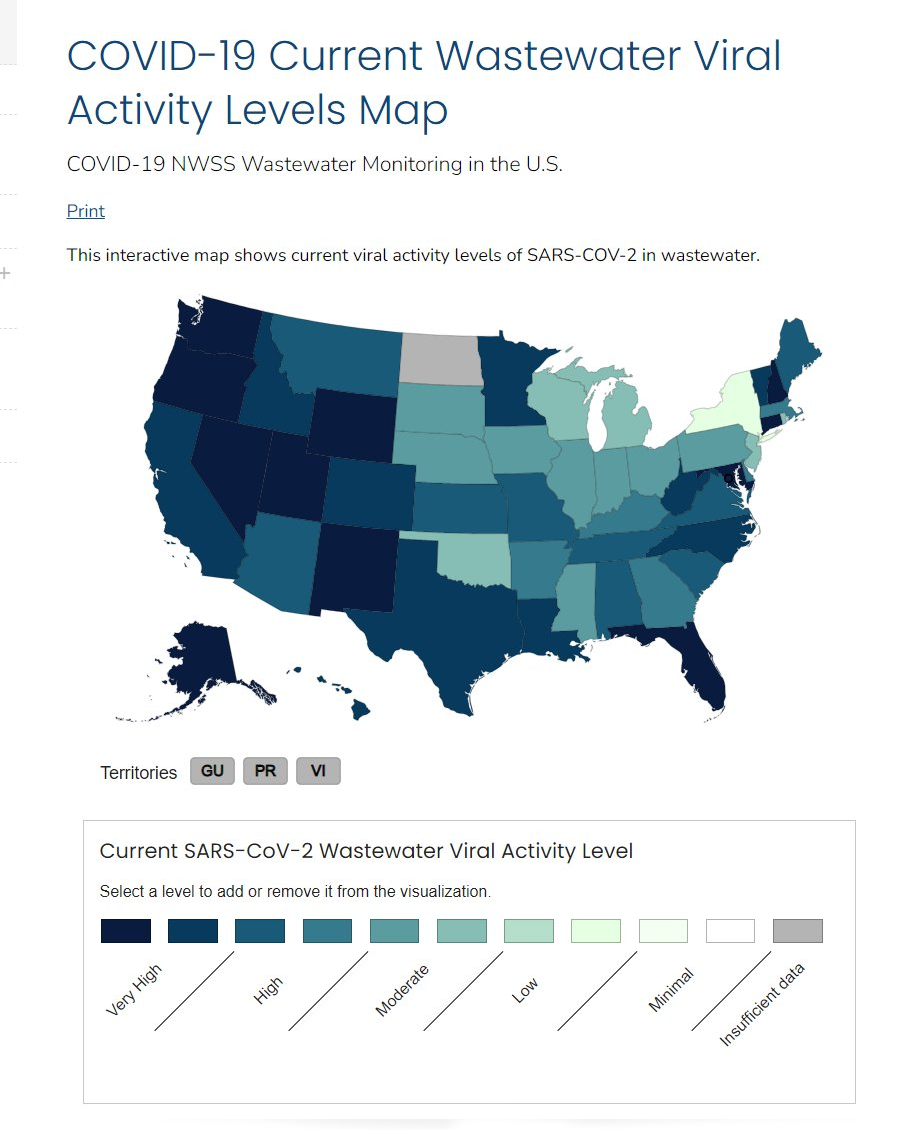

Another bad portent is that levels of the virus in wastewater — a key predictor of community spread — have reached the “high” or “very high” category in 35 states and D.C., especially in the West:

There’s an additional new wrinkle this summer – the just-completed Republican National Convention in Milwaukee and the upcoming August Democratic confab in Chicago are prototypic “superspreader” events, with thousands of people crowded together chanting, shouting, and singing — and with nary a mask in sight (well, except possibly at the DNC!).

This resurgence is a clear warning: If you’re feeling under the weather, with congestion, runny nose, headache, fever, sore throat or coughing, it’s likely COVID, so get tested.

A sliver of good news is that despite the increase in infections, the severity of disease remains lower compared to previous peaks, thanks largely to enhanced population immunity from some combination of vaccination and previous infection. But that could change, with the appearance of new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

It is noteworthy that even when the acute illness is mild and self-limited, the long persistence of symptoms or the appearance of new ones — “long COVID”— remains a risk.

Why does COVID keep making a summer comeback? Three main factors: changes in human behavior, the virus’s high mutation rate, and waning immunity.

During the sweltering summer months, people retreat indoors where air circulation is often poor, facilitating the spread of the virus. Also, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, mutates roughly twice as fast as the flu virus, with the latest variant, KP.3.1.1, adept at evading our initial immune defenses. Finally, immunity from winter infections and last fall’s booster shot has waned, leaving many vulnerable.

CDC guidance

The most recent guidance for those infected is somewhat tricky. If you contract COVID, the Centers for Disease Control suggests isolating until your fever has resolved for 24 hours or your symptoms improve. However, because many people remain contagious beyond this point, the CDC advises five days of additional precautions, such as wearing a mask or testing before visiting highly vulnerable individuals.

Ideally, you should isolate until an at-home COVID test turns negative, which could take anywhere from 3 to 15 days from the onset of symptoms. Given the cost of tests and the financial burden of prolonged isolation, if you must leave isolation early, the CDC recommends wearing an N95 mask.

Paxlovid, an antiviral drug, remains a key tool for treating COVID, particularly for those over 65 or who are not up-to-date on their vaccinations. Although Paxlovid has proven effective for this group, it has shown limited benefits for others, neither significantly reducing the duration of illness nor preventing long COVID in vaccinated individuals.

Travelers should remain cautious, especially when flying. Airports and airplanes, particularly before takeoff when ventilation is limited, are prime environments for spreading the virus. Longer flights pose a greater risk; every additional hour of flight increases the likelihood of infection by more than 50%.

Why does COVID surge each summer?

The cause of COVID’s persistent summer surges remains something of a mystery. Unlike the flu, which typically peaks in winter, COVID has spiked in both hot and cold months. This could be due to several factors: the virus’s resilience, human behavior, and environmental conditions. The flu struggles in summer heat, but SARS-CoV-2 is hardier, surviving conditions that typically suppress other respiratory viruses.

In the decades ahead, climate change could make flu containment even more challenging. Increasingly severe heat waves could drive more people indoors during the summer, creating ideal conditions for spreading the virus. This summer surge, particularly in the heat-plagued western U.S., could foreshadow an even more precarious future.

The human immune system also plays a role. Immunity from past infections or vaccinations wanes over time, making people more susceptible to reinfection. While memory T cells from previous exposures help prevent severe illness, waning antibodies mean people can still contract and spread the virus.

Prevention

Vaccination remains crucial. Earlier this year, the CDC recommended a second booster for those 65 and older, but uptake is only around 20%, and it’s unclear to what degree it would offer protection from new variants. An updated version vaccine that targets more recent circulating variants is expected this fall.

Aside from vaccination, familiar preventive measures remain effective: masking, improving indoor air quality through ventilation and filtration, and avoiding crowded indoor spaces.

More than four years into the pandemic, most people have some level of immunity, and newer iterations of the virus are not as deadly as earlier ones. However, it still poses risks, especially to the medically vulnerable, and the threat of debilitating long COVID remains very real.

A previous version of this article was published by the Genetic Literacy Project.