Very few of us read medical papers and even fewer reach research from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), so it is not surprising that an eyebrow-raising study was primarily shared with the public by the NY Times. Here is the lead:

“Obstetricians are more likely to give Black women unnecessary cesarean sections, putting those women at higher risk for serious complications like ruptured surgical wounds.

That’s the conclusion of a new report of nearly one million births in 68 hospitals in New Jersey, one of the largest studies to tackle the subject.

Even if a Black mother and a white mother with similar medical histories saw the same doctor at the same hospital, the Black mother was about 20 percent more likely to have her baby via C-section, the study found.

The additional operations on Black patients were more likely to happen when hospitals had no scheduled C-sections, meaning their operating rooms were sitting empty. That suggests that racial bias paired with financial incentives played a role in doctors’ decision-making, the researchers said.”

Let me be honest: these studies give me pause. I find it difficult, but not inconceivable that physicians act out of financial incentives while putting their patients at risk. So, given those findings, I read the actual study, not the media gist.

A Quick Primer on Cesarean Delivery (C-section)

Delivery by Cesarean can be lifesaving for mother and baby, and there is a persistent difference in the rates of C-sections between non-Hispanic white mothers (29.3%) and Black mothers (34%). As with any medical intervention, those lifesaving benefits are balanced by a small number of maternal complications and a growing body of evidence that children may be impacted, e.g., gut microbiome.

Many factors are attributed to the performance of a C-section; we will return to the primary consideration, medical indications, momentarily. Among the socioeconomic determinants is patient preference, although few women begin by requesting a section over vaginal delivery, and those requests are entangled with health literacy and subsequent self-advocacy, insurance coverage, and the “use [of] different hospitals, practices, or providers.” Those health systems and physician differences include the oft-suggested implicit biases and racially based algorithms.

For many women at high risk, a C-section is a scheduled event. For women who, during a “trial of labor,” develop complications or whose baby evidence “fetal distress,” an unplanned or Emergency C-section is performed.

The study was designed to better understand the racial disparity in C-section rates. Their data came from the New Jersey Electronic Birth Certificate (EBC) records for 68 unique hospitals and 1,704 physicians, a record of essentially all births from 2008 to 2017. The records include information on delivery, maternal risk factors, maternal and infant outcomes [1], and the usual patient demographics. Information on 71% of the physicians’ practices, along with their gender and race, were obtained from other datasets.

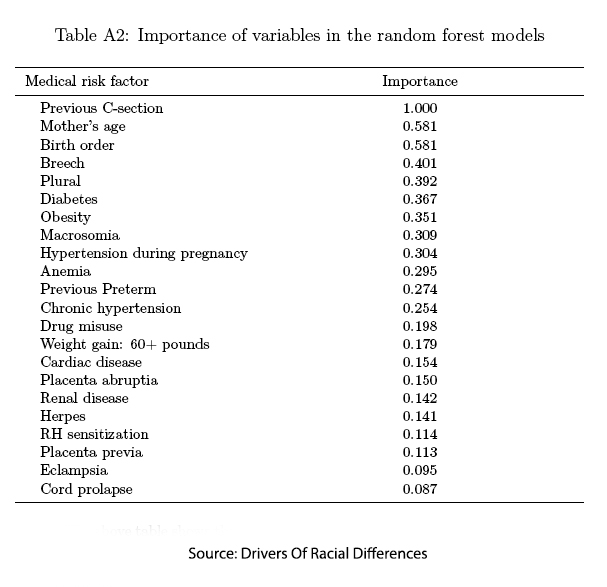

The researchers focused on unscheduled “Emergency” C-sections to eliminate the possibility of patient preference and because that allowed them to analyze cost and timing. Because there are many medical reasons to perform an unscheduled C-section, the economists applied an algorithm of their design to stratify women into five increasingly at-risk groups and thereby allow a comparison based more solely on race than medical factors. Here are the weighted (Importance) variables used in predicting the risk of C-section

The algorithm did “an excellent job sorting mothers into risk groups” with one exception – the basis of all their subsequent findings, Black mothers were “over-represented in the lowest risk quintiles.”

“Over our sample period, Black mothers in New Jersey with an unscheduled delivery were on average 24.8 percent more likely to have an unscheduled C-section than non-Hispanic white mothers. This disparity is most pronounced for mothers in the lowest risk quintile (149.4 percent), although a slight gap exists even among mothers in the highest risk quintile (12.3 percent).”

Did that over-representation impact their findings? Look at the data.

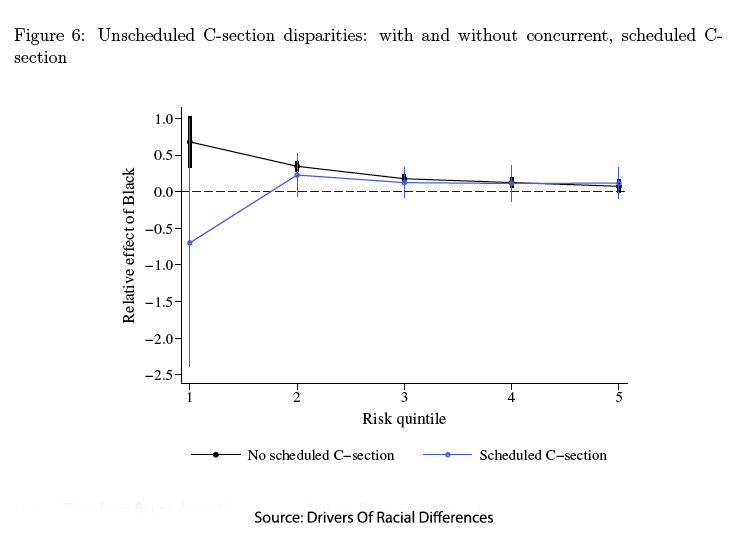

The only risk level that shows a significant difference is the lowest-risk group, the group over-represented by Black mothers.

Implicit bias

While Black mothers are more likely to undergo C-sections, as it turns out,

“Black doctors are just as likely to perform unscheduled C-sections as doctors of other races. … although female doctors are slightly less likely to perform unscheduled C-sections, we find no evidence that the racial gap is different between female and male doctors.”

So much for implicit bias and the continuing drumbeat that a solution to “racial gaps in treatment is to encourage racial concordance between providers and patients.”

For Complications, It is not so Complicated.

While acknowledging that complications for mother and child are less frequent following unscheduled delivery because the preponderance of high-risk patients has been identified before labor, the study reports that Black mothers and children still have higher complications than their White counterparts after unscheduled delivery. We have no breakdown on the specific complications associated with the mother, and the absolute difference is 1.2% (7.1 percent of Black mothers have at least one postpartum complication compared to only 5.9 percent of white mothers), which explodes to the more reported relative difference of 20%.

The researchers note that the primary driver of neonatal complications is admission to the Neonatal ICU (NICU). They go on to torture the data and write,

“Similarly, 11.2 percent of infants born to Black mothers with unscheduled deliveries have any postnatal complication compared to 7.1 percent among babies born to white mothers.

…the results suggest that the marginal C-sections done on low-risk Black and white mothers because there is the capacity for doctors to do so, harms infant health.”

I would respectfully suggest that the greater admissions to NICU reflect the good judgment of physicians in identifying at-risk deliveries and the erroneous categorization of these women as “low-risk.”

It’s all about the Benjamins

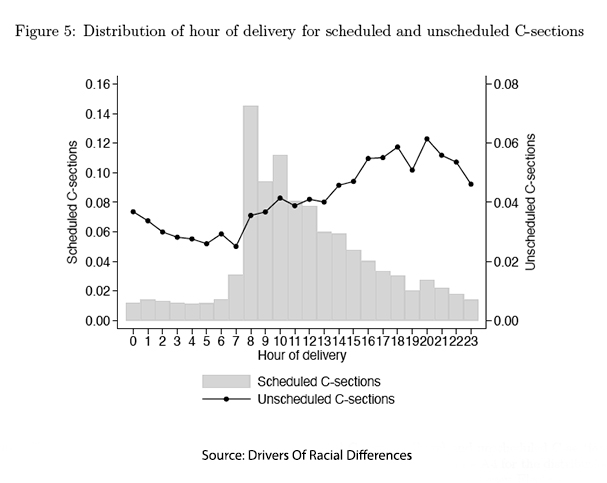

The three authors, all economists, point out that a hospital only makes money when the Labor and Delivery Rooms (L&D) are being used. Having failed to identify the hospital or physician as a cause, one cannot fault them for looking for a monetary cause. They now consider whether the timing of C-sections is a cause – are more Black women undergoing C-sections in those unused off hours?

Physicians and hospital staff, like all of us, like to work during “routine” hours. You can see that for medical folks, the routine runs from about 7 AM till 10 or 12 PM. Overlaid on our routine hours are the timing of those unscheduled C-sections. There are a few pertinent contextual notes. First, the unscheduled C-sections use the scale on the right which is half that on the left, so unscheduled C-sections are visually over-represented and are more a quiet backbeat on the L&D tempo. More importantly, those unscheduled cases are being done throughout the routine hours, increasing as there is more capacity.

Economists believe we fill those gaps because we are economic animals seeking the Benjamins. But the reality is that a C-section because of “fetal distress” gets the next available room, and the scheduled case gets pushed back, or as we say in the trade, bumped. The use of the term “Emergency C-section” to describe unscheduled C-sections is a bit of a clinical misnomer; in cases of labor failing to progress, there may indeed be time to wait for a room to open.

The researchers report:

- “Among high-risk mothers with unscheduled births, …[there are] no significant difference in the effects on Black and white mothers.”

- For low-risk mothers, the rate of unscheduled C-sections performed during scheduled C-sections, when the planned cases get bumped because of a true emergency, “the white rate for the lowest risk births falls to 1.6 percent, and the Black rate falls to effectively zero, reducing the gap to insignificant…”

- Only in the later part of the day is there a disparity in unscheduled C-sections and only for the low-risk, where I again point out Black mothers are over-represented. The absolute difference is 3.2% (8% for Black mothers versus 4.8% for non-Hispanic White mothers), heralded by the relative difference of 67.9%.

These findings lead the researchers to conclude:

“These findings suggest that the racial gap is driven by a higher propensity of doctors to perform C-sections on low-risk Black patients when the costs of doing so are low.”

But isn’t it equally probable that the indication for C-section allowed them to wait on indicated cases and not disrupt the daily schedule? It would also be consistent with the fact that race played no role when a case had to be bumped.

This study may have raised eyebrows, but its conclusions stand on shaky ground. The over-representation of Black mothers in the lowest-risk groups skews the results, and the authors’ fixation on economics overshadows the reality of medical judgment in the delivery room. There are disparities in C-section rates, but blaming it on racial bias and financial incentives are convenient narratives that obscure complex truths.

[1] Postpartum maternal complications included: “postpartum hemorrhage, major puerperal infection, venous complications, pyrexia, pulmonary embolism, and other postnatal complications.” Infant health complications included “admission to a NICU, 5-minute Apgar score below 7, mechanical ventilation, and significant birth injury.”

Source: Drivers Of Racial Differences In C-Sections NBER Working Paper 32891