Frankly, I have been a bit mystified by the recent push to make America healthy again. Why now and why individuals like Calley Means and RFK Jr? While the simple answer revolves around the presidential election, these are individuals and groups that can play the long game. Falling back on the 70s mantra, “follow the money,” I came across a more complex reason, hidden, as always, in plain sight – the Farm Bill.

We urban types can be forgiven for not attending to legislation entitled the Farm Bill. It weighs in just shy of 1000 pages and sets the five-year budget for agriculture and nutrition. It was not passed by our dysfunctional Congress in 2023, nor does it look like it will be passed this year, merely extended in that way our representatives have of kicking the can down the road. Perhaps we should be more understanding of our legislators; after all, the amount being set aside is estimated to be $1,500,000,000,000 (1.5 trillion), and you know none of these individuals will read anywhere near 1000 pages of legalese.

Like many other titles given to legislation, viewing this solely as a farm bill is a misnomer. While historically, legislation has been approved to protect farmers almost since our founding; federal legislation went big during the Depression when the New Deal introduced the

- Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) providing 12-month loans to farmers at a fixed price for their crops, acting as a price floor.

- Farm Credit Administration (FCA) refinancing farm mortgages at lower rates.

- Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) paying farmers to replace cash crops with soil conservation grasses to stabilize crop prices by limiting production

- A measure allowing for a consumer nutrition program

That nutrition program was a way to take excess crops purchased from farmers to support prices and distribute them to those of us in need, what we today call the “food insecure.” Beginning in 1939, people on “relief” could purchase Orange stamps, used to purchase any food, and receive Blue stamps, worth half that value, to purchase food determined by the USDA to be surplus. [1]

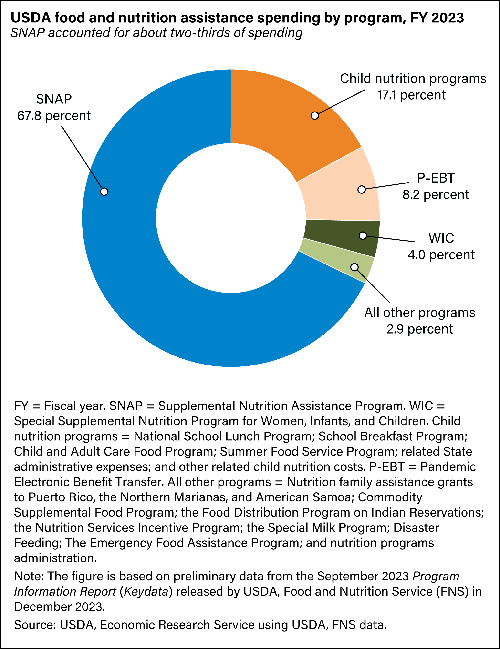

As with everything bureaucratic, the Farm Bill grew over time, fertilized by special interests and the need to be re-elected and watered by the monies given to farming, big and small, and those in need. But today, an estimated 84% of that $1.5 trillion is to be spent on SNAP, the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program.

Today, SNAP provides food to 42 million people, including 17 million children. One of the sticking points in the legislation currently before Congress is a reduction in SNAP spending by not adjusting the benefit for inflation. However, that is not Calley Means's focus; instead, he wants these programs to take on what we know as “Food as Medicine” or how a more nutritious diet will reduce the incidence of chronic diseases.

Today, SNAP provides food to 42 million people, including 17 million children. One of the sticking points in the legislation currently before Congress is a reduction in SNAP spending by not adjusting the benefit for inflation. However, that is not Calley Means's focus; instead, he wants these programs to take on what we know as “Food as Medicine” or how a more nutritious diet will reduce the incidence of chronic diseases.

This ideological belief, not some scientific consensus, fuels Mr. Means and Kennedy’s newly spoken concerns. We are discussing who sits on the scientific committees that determine our Dietary Guidelines because those guidelines are the basis for calculating SNAP benefits.

Following the Money

The USDA has been suggesting healthy diets to the American public for over 100 years. Each plan includes the oft-mentioned market basket, “defining weekly quantities of food categories in their purchasable forms that, together, make up a healthy, practical diet for various age-sex groups.” There are four plans based on the cost level of the basket, determined by average food prices and available income. The Thrifty Food Plan, based on the lowest available income,

“outlines nutrient-dense foods and beverages, their amounts, and associated costs that can be purchased on a limited budget to support a healthy diet through nutritious meals and snacks at home.”

It is that market basket that determines the maximum allowable SNAP benefit. While the cost of the basket is updated annually, the content of the basket was just updated recently to replace the older contents determined in 2006. Here is the key: the federal Dietary Guidelines determine what goes into that basket. That is why determining the Dietary Guidelines attracts so much lobbying and money. Control of the guidelines ultimately means control of all the funds spent by SNAP.

What do we know about “Food as Medicine.”

It is an alluring phrase; at the biochemical level, we are what we eat – except not entirely. We are, in terms of our health, genes, environment, physical activity, etc. Interestingly, the experts who developed the Dietary Guidelines have changed their focus over time. The guidelines are less interested in specific foods or nutrients and now reflect our overall dietary pattern – a regulatory version of everything in moderation. In addition, the guidelines reflect our nutritional needs as we age; a toddler's needs differ from that of their parent or grandparent.

Most academic studies of our health outcomes based on nutritional intake use the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), one of several scoring systems for determining the nutritional value of a diet. HEI is based on the federal Dietary Guidelines, so it is particularly salient. In my less-than-complete literature review, I came across this meta-analysis in Advances in Nutrition, which seems to be the consensus.

There was about a 10% reduction in cancer mortality between those with the highest (best) HEI and lowest, a 20% reduction in cardiovascular mortality. Of course, to put this finding into perspective, the meta-analysis does not define the highest HEI. The HEI score when following all the dietary guidelines is 100, and the average score for adults in the US is 58.

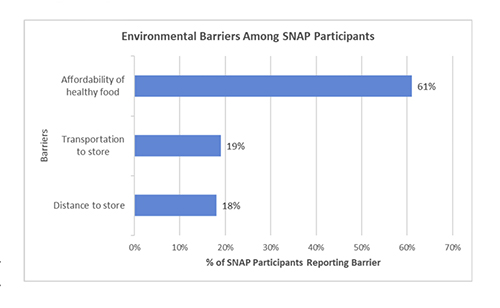

Given that we have been told about the federal Dietary Guidelines for years, a score of 58 seems to suggest that all that advice has barely moved the nutritional needle. Many experts criticizing SNAP point to the choices SNAP recipients make–poor nutrition education resulting in poor nutritional choices. Or that nutritional food deserts are making it challenging to access nutritional foods. However, those explanations are in marked contrast to the statements made by SNAP beneficiaries. In a survey done by the USDA, the most significant barrier to a nutritious diet was the time necessary to make a meal – 30% vs. 16% that cited a lack of education or the 11% that cited a lack of cooking skills.  For comparison, a study in the general population indicated that 28% lacked cooking skills, and 21% cited lack of time. So, SNAP beneficiaries are not that different from other economic groups.

For comparison, a study in the general population indicated that 28% lacked cooking skills, and 21% cited lack of time. So, SNAP beneficiaries are not that different from other economic groups.

SNAP beneficiaries differ from the general public in other ways, primarily, no surprise, in the ability to purchase more nutritious foods, which means fruits and vegetables, not organic varieties. The issue of distance and transportation creating those food deserts is far less of a barrier. And with their impoverished circumstances comes a lack of storage for fresh or cooked foods.

None of these real barriers to nutritional eating, for treating food as medicine, come from tweaking the federal Dietary Guidelines or the Thrifty Food Plan. Focusing on those issues is focusing on distributing the Benjamins to the non-beneficiary stakeholders. Increasing SNAP funding will make food more affordable. Improving low-income housing will enhance food storage. Improving public transit and home delivery will reduce the burdens of getting food. None of these ideas are being presented by Mr. Means or Kennedy because their interest lies in the power to move federal largesse in their direction.

Ultimately, the SNAP debate isn’t about making anyone healthier; it’s about who controls the narrative—and the funds. While we’re all being distracted by shiny slogans like “Food as Medicine,” the real maneuvering happens in the back rooms where billion-dollar budgets are carved up like last year’s Thanksgiving turkey.

[1] Mabel McFiggin of Rochester, New York, was the first recipient of “Food Stamps” in May 1939. It required four months before Nick Salzano, a retailer, was caught violating the program.

[2] The data on the sole role of diet in our health is mixed. For diseases involving an underlying metabolic issue, e.g., diabetes, gluten allergies, and, to a lesser degree, cardiovascular disease because of cholesterol, tailored dietary recommendations alone have been helpful but not as beneficial as a nutritious diet as part of a healthy lifestyle.

Sources: Envisioning a more equitable and inclusive Farm Bill Brookings Institute

USDA Food Plans US Department of Agriculture

The Healthy Eating Index-2015 and All-Cause/Cause-Specific Mortality: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis Advances in Nutrition DOI: 10.1016/j.advnut.2023.100166