Misguided COVID-minimizers like to say that COVID-19 is no worse than a cold that lasts a few days and then disappears without any sequelae. They’re so wrong, and the evidence of that continues to mount.

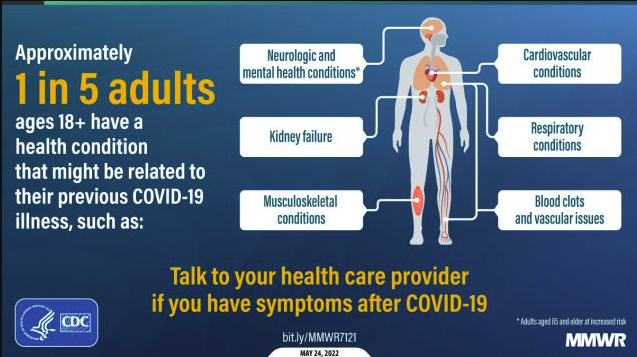

In 2022, the CDC identified the onset of new conditions following infection that "might be related to their previous COVID-19 illness":

Source: CDC

Many of those suspicions have been borne out, and our knowledge base has been expanded by subsequent research. A study published last year in the journal The Lancet Respiratory Medicine that examined the longer-term impacts of COVID found that five months after infection, nearly a third of patients displayed abnormalities, some of which reflect tissue damage, in multiple organs. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of patients showed a higher burden of abnormal findings involving the lungs, brain and kidneys compared to controls. Lung abnormalities were almost 14-fold higher among COVID patients discharged from hospital than in the control group, while abnormal findings involving the brain and kidneys were three and two times higher, respectively.

A more recent study by British researchers, published in JAMA Psychiatry in August, describes mental health sequelae of COVID-19 infection and illustrates the critical role vaccination plays in mitigating these effects. Encompassing more than 18 million people, it found that those who were unvaccinated and contracted severe COVID have a significantly heightened risk of developing various mental illnesses, a risk that can persist for up to a year after infection.

The U.K. study provides compelling evidence that the virus poses more than a short-term physical threat — it can leave lasting scars on mental health, especially for those who experience severe illness and hospitalization. The study tracked various mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), eating disorders, addiction, self-harm, and suicide. The findings are alarming: The incidence of these conditions spiked in the weeks following a severe COVID diagnosis, particularly among the unvaccinated.

In unvaccinated individuals, the likelihood of developing depression after hospitalization for COVID was up to 16.3 times higher than in those who did not contract the virus. This elevated risk did not diminish with time; it persisted, often affecting mental health for up to a year after the initial diagnosis. The study’s results add to a growing body of evidence that underscores the severe and prolonged mental health impacts of COVID, especially when compounded by the stress and trauma of a serious infection.

Vaccination as a Protective Factor

A significant finding of the study is the protective effect of COVID vaccination against the effects on mental health. The study found that vaccinated individuals who contracted COVID were far less likely to develop mental illnesses than their unvaccinated counterparts. This difference was particularly pronounced in cases of severe cases of COVID leading to hospitalization.

For example, while the incidence of depression and other serious mental health conditions surged in unvaccinated individuals following a severe illness, vaccinated people had significantly lower rates of post-infection mental illness, with some conditions showing nearly negligible elevation above baseline, compared to those who had not been vaccinated.

This stark contrast is a reminder that vaccination is a crucial tool not just in preventing severe physical illness, hospitalization, and death, but in safeguarding mental health in the aftermath of a COVID infection.

Broader Implications for Public Health

The implications of these findings are critical for both public health strategies and individuals’ decision-making as we approach a likely winter surge of COVID. As the world continues to grapple with the long-term consequences of the pandemic, understanding the broader impacts of COVID on mental health becomes increasingly important.

Serious mental illnesses, such as those linked to severe COVID, can be associated with longer-term adverse outcomes and the need for intensive (and expensive) healthcare, and mitigating these risks through vaccination could relieve some of the burdens on healthcare systems already stretched thin by the pandemic.

Understanding the Mechanisms

The U.K. study also delves into the potential mechanisms behind the increased incidence of mental illnesses following COVID infection. These could include both physiological pathways — such as inflammation and microvascular changes triggered by the virus — and psychosocial effects, including the anxiety and trauma associated with the illness and its potential long-term consequences. The researchers note that the rapid rollout of COVID vaccines was a crucial component of the public health response, and their findings suggest that vaccination also mitigates these adverse mental health outcomes.

However, the study acknowledges that more research is needed to fully understand the complex relationship between COVID infection and mental health. Differentiating between hospitalized patients and the general population in future studies could provide deeper insights into how the severity of COVID influences subsequent mental illnesses. Additionally, investigating how factors like age, sex, ethnicity, and pre-existing mental health conditions affect this relationship could help to tailor public health strategies to those most at risk.

Another study, published on August 29 in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia found other examples of brain dysfunction and clinical deterioration into dementia following COVID infection. This is an excerpt from the abstract:

Many [COVID-]positive individuals exhibit abnormal electroencephalographic (EEG) activity reflecting “brain fog” and mild cognitive impairments even months after the acute phase of infection. Resting-state EEG abnormalities include EEG slowing (reduced alpha rhythm; increased slow waves) and epileptiform activity. An expert panel conducted a systematic review to present compelling evidence that cognitive deficits due to COVID-19 and to Alzheimer's disease and related dementia (ADRD) are driven by overlapping pathologies and neurophysiological abnormalities. EEG abnormalities seen in COVID-19 patients resemble those observed in early stages of neurodegenerative diseases, particularly ADRD. It is proposed that similar EEG abnormalities in Long COVID and ADRD are due to parallel neuroinflammation, astrocyte reactivity, hypoxia, and neurovascular injury. These neurophysiological abnormalities underpinning cognitive decline in COVID-19 can be detected by routine EEG exams.

The study did not address the effects of vaccination on their findings.

A Call to Action

As we move forward in the post-pandemic era, studies of the relationship between COVID infection and mental illness are a reminder of the multifaceted impact of COVID. It is clearly not just about surviving the virus; it’s also about understanding and addressing the long-term consequences, including on mental health. Vaccination is, thus, not only a tool to lessen the spread of the virus and reduce the severity of illness but a critical intervention to protect the mental well-being of those who contract COVID.

In conclusion, as we continue to navigate the post-COVID-pandemic era, vaccination remains critically important, a shield not just against the physical ravages of the virus but also against the insidious mental health deterioration that can follow in its wake. With a possible COVID winter surge in the offing, getting a vaccine booster should be on everyone’s to-do list, so that holiday get-togethers don't become superspreader events.