A recent headline proclaimed, “Lifestyle medicine education empowers clinicians.” The article focused on a recently published paper in the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. The write-up stated

“The findings are important because, while lifestyle behavior changes are often the optimal treatment option in clinical practice guidelines for noncommunicable chronic diseases, many clinicians cite their lack of knowledge and training in lifestyle behavior interventions as a barrier.”

Digging into the paper reveals why science journalism is difficult and how easy it is to walk away with an incomplete picture. Let's dig into the study to determine what it looked at and what it concluded.

The Study

This study is a simple pre-post survey design on knowledge, confidence, and attitudes upon completing an LM training course. Nothing can be said about whether or how physicians changed their practice because this study simply did not look at that at all. It is a simple: “Did people reflect that they had learned more, changed their attitudes, or confidence.” Survey answers were recorded on a five-point scale where a higher score reflected more confidence, knowledge, or positive attitudes.

Pre-course overall LM knowledge and confidence scores averaged 3.21 and 3.22 (out of 5). Post-course, there were statistically significant increases, with knowledge improving by 0.47 points and confidence by 0.53 points.

Most people already came in with a decent baseline since the average overall knowledge score was 3.21 out of 5. The typical person moved just under half a point on the knowledge scale, which puts the average knowledge at 3.678 out of 5 after the training - a modest increase.

Knowledge, Confidence, Attitudes

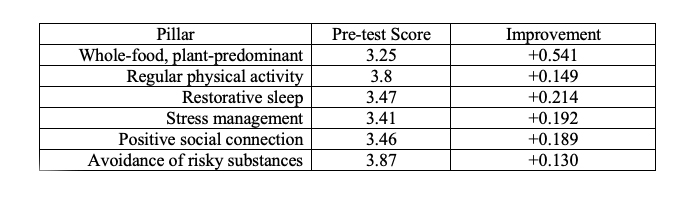

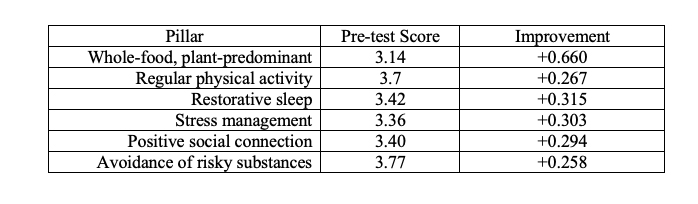

The knowledge physicians gained pre to post-course scores across the six pillars of LM were all statistically significant. However, there is a difference between statistical and practical significance.

Most areas improved slightly, around 5% from the baseline pre-score; only “avoidance of risky substances” got a 4, but it started at nearly 3.9. According to these survey results, practitioners' knowledge of lifestyle medicine’s pillars began and remained average.

So what about confidence in speaking about these items with patients?

The gains in confidence scores were generally slightly larger than in knowledge. However, while statistically significant, there isn't much change. The biggest change in knowledge and confidence was in the “whole-food, plant-predominant diet.” The training brought the weakest area of knowledge and confidence up to the middle of the pack, which is not nothing - just above average. Confidence does not seem to be an issue for physicians.

LM is touted as a great way to prevent and treat noncommunicable chronic diseases, and the study asked physicians about their attitudes toward this topic. Initially, the favorable response to “Likely to provide LM for prevention of chronic disease” started very high, 4.79 out of a possible 5. It decreased, at least statistically, after training to 4.72. I would argue that there was effectively no change here, though the little impact training had was in the wrong direction.

What Did We Learn?

There isn't much that we can take from this study. This study does nothing to advance our knowledge of LM. Participants seemed to have decent baseline knowledge, confidence, and attitudes, and the LM course didn't move much on any of the indicators. The most movement was in the diet category, the weakest category across the board. We don't know if any people who underwent the training changed how they practiced. The survey indicates not much knowledge was gained, that confidence outpaced knowledge, and there was virtually no movement in intention to change practice.

All of this seems pretty far from the “empowering” headline.

People who work for the American College of Lifestyle Medicine designing and implementing a continuing medical education curriculum should not be news. Does LM education “empower” physicians? That's a bit much. The news write-up implied, without a source, that physicians cite a lack of knowledge and training as a barrier to practicing LM. These survey results suggest that knowledge is not a significant barrier and that this training did not significantly change intentions or attitudes. When you start with a relatively high baseline in these areas, it can be difficult to shift even higher.

The authors conclude:

“The ACLM Essentials course is a cost-effective and scalable tool to deliver moderate increases in LM knowledge and practice to far-reaching and diverse groups of healthcare professionals. Health systems looking to increase LM implementation can promote this program as one component in a more comprehensive strategy that also addresses cultural and environmental barriers to LM practice.”

However, according to their results, knowledge, confidence, and attitudes aren’t overly problematic for the practice of LM. What, then, are the actual barriers to practicing LM? I would argue that LM, driving in the public health lane, proposes an individual-level solution to largely systematic problems. We put too much emphasis on physicians being able to address every issue for us, and that's not only unfair but is setting up physicians for failure. An article from the British Journal of General Practice put it beautifully,

“With this in mind, we focus on the unintended consequences of uncritical endorsement and application of lifestyle medicine, including the infiltration of pseudoscience, profiteering, and the potential for widening health inequalities by a continued focus on the ‘individual.’ We stress the need for greater attention to public health and community-level interventions and a more critical approach to current practice.”

I'm all for discussing good lifestyle habits and choices with patients, but these conversations largely ignore people's collective realities. That's not something physicians can fix, nor should we expect them to. LM isn't an advancement in medical practice so much as the advancement of the idea that these issues, along with other social determinants of health, can and should be fixed at the individual level. That's missing the forest for the trees.