With rare exceptions, the chemical reactions that take place in our bodies are catalyzed by enzymes. These biological catalysts evolved to make essential reactions happen about a million times faster than they otherwise would. In short, life depends on enzymes.

One of these exceptions is the nonenzymatic (just plain chemical) reaction that creates glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) from glucose. Unlike a one-time blood sugar test, which can swing widely depending on the moment, HbA1c accumulates over months. That makes it a far better indicator of long-term glucose levels and diabetes risk than a fingerstick reading.

And here’s something odd: HbA1c is formed not by any specialized enzyme but by a fundamental reaction simple enough for sophomore organic lab. It is the very slowness of that chemistry that makes the test so powerful.

Can't avoid a little chemistry. Sorry. I'll keep it to a minimum.

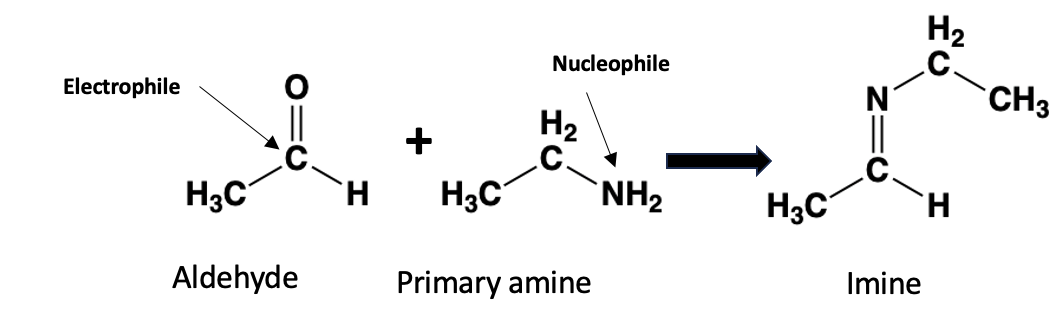

At its heart, the reaction is straightforward: an amine reacts with an aldehyde to form an imine. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An aldehyde (pictured: acetaldehyde) is electrophilic (seeks electrons) and reacts with a primary amine (pictured: ethyl amine), which is a nucleophile, donates electrons, to form an imine. The byproduct is a molecule of water.

In fact, the reason that the HbA1c test works at all is that the reaction that forms it is not enzyme-catalyzed and is, therefore, very slow, allowing the test to provide an average measurement of blood glucose over three months.

It also explains why we have not developed an enzyme to facilitate its biosynthesis (more on this later).

What does this have to do with glucose?

If you examine the chemical structure of glucose (left), you may wonder, and rightly so, where the aldehyde and amine groups are lurking. In other words, how could this simple chemical reaction even occur, let alone tell us anything about sugar intake? But glucose exists in two rapidly interchanging forms, open and closed. (Figure 2)

1. Glucose is an aldehyde. Sometimes.

At first glance, glucose doesn’t look like it has the right parts. But molecules can be trickier than they appear, sometimes, annoyingly so. For reasons that are beyond the scope of this article, it shifts between two rapidly interchanging isomeric forms – open and closed – that are in equilibrium with each other. In its closed form, there is nothing to react with an amine. But in the open form, voilà – an aldehyde (red oval) appears, and it is this form that does the "work." (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Glucose in its closed (right) and open (left) forms. The aldehyde is shown in a red circle. The blue and red stars indicate the corresponding atoms in each form. The solid red line shows the bond that breaks and reforms the ring.

2. Where is the amine?

Again, this isn't obvious (unless you've spent 40 years having it drilled into your head). But the answer should be obvious: hemoglobin (Figure 3). After all, it is hemoglobin that is chemically modified to form HbA1c, but does it contain an amine that allows it to couple to glucose?

Figure 3. Proteins are made of 20 different amino acids. One of them (lysine) contains a primary amine (NH2). This enables hemoglobin to form covalent bonds with glucose (bottom), making a stable [1] and measurable reaction product.

Why are there no enzymes involved?

The human body has evolved so that it produces thousands of enzymes. Enzymes perform life-giving chemical reactions in a small fraction of a second. Without these enzymes, these same essential reactions would be far too slow to support life.

Yet, this process proceeds without any enzyme to promote it? Why? Cavemen's diets did not consist of Oreos, Baby Ruths, or milkshakes. A diet high in sugar and carbohydrates was hardly a problem. Therefore, given low glucose levels, there was no reason for the body to develop an enzyme capable of catalyzing the formation of HbA1c from excess glucose.

Ironically, this simple reaction is medically helpful because it is so slow, allowing months' worth of HbA1c to form and give a readout on cumulative sugar intake. If the reaction occurred immediately, it would be no more useful than a needle stick measurement.

So if that Three Musketeers bar is calling your name, go ahead. Just remember — your hemoglobin may tattle on you at your next checkup.

NOTE:

[1] Before chemists start screaming at me, the initial adduct of the hemoglobin-glucose reaction is unstable, but rearranges to something that is stable. No, I'm not going into it.