The beauty of the unfettered market is that through an "invisible hand," supply and demand match and value more frequently triumphs over "lemons." Of course, that market does not exist, not even when initially described by Adam Smith. The market of healthcare is different. There is a greater insensitivity to prices, who wouldn't pay or have paid for them the cost of being healthy? Variations in outcome, especially to the downside, are met with greater resistance when possible; after all, healthcare is a matter of life and death, with a bit of quality of life thrown in.

Today's healthcare market is regulated, with fixed prices, and some, if not many, would say insider fixes. Despite that, many feel that a more unfettered market would correct some of those problems. Two phrases often bandied about are consolidation to create economies of scale and standardization to remove some of the unwarranted and unwanted variability in products, or in the case of healthcare, outcomes. A paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics looks at those economies, scale, and standardization in one area of healthcare, dialysis.

Why look at dialysis?

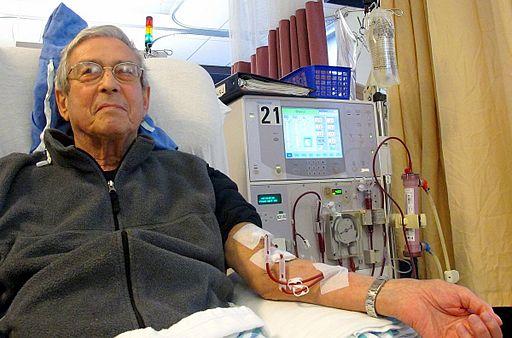

Dialysis cleans the blood of impurities that develop in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Without it, they will die over a few weeks. For most individuals, dialysis means being hooked to a machine leaching impurities from their blood, for three to four hours three times a week. Chronic dialysis, follows a set pattern, making it very amenable to standardization. Additionally, dialysis providers have rapidly consolidated, offering economies of scale.

- There are roughly 6,000 dialysis centers.

- From 1998 to 2010, consolidation through acquisition reduced the number of independent centers by 50 to 150 annually.

- 90% of patients requiring dialysis, use these centers

- Two companies control 60% of the Medicare patients and obtain 90% of the profits.

Many dialysis outcomes are easily quantitated.

- The urea reduction ratio is a measure of how well a patient's blood is cleared of impurities. While the time to achieve a URR varies for each patient, "the standard of care is that a dialysis session should continue until a patient achieves a URR of 0.65."

- Because of the kidney's role in creating red blood cells, dialysis patients are anemic, requiring medications to stimulate red cell production (Erythropoietin stimulating agents) There are set ranges, too low (below 10 grams Hb) and the patient is short of breath, too high (over 12 grams Hb) and the blood thickens, becomes more "clottable," patients experience higher rates of stroke or heart attacks

- Patients on dialysis have suppressed immune systems, and the thrice-weekly needles and tubing puts them at risk for severe infections, e.g., septicemia a disease frequently resulting in hospitalization

- Patients on dialysis have two ways of getting off the care. They can if lucky, get a transplanted kidney, or they die

Finally, the cost of dialysis is borne primarily by the Federal government; 6 % of Medicare's budget goes to dialysis and its associated costs. Federal coverage of dialysis began in 1973, forty-six years ago, and we have detailed financial and health information on this program and its beneficiaries. The researchers used that data to analyze the spending and organization of independent dialysis centers before and after their acquisition. As a result, patient variables did not change; any "treatment effects" were due solely to acquisition. [1]

The effect of consolidation

Consolidation did not result in greater competition. Given that Medicare fixes payments for dialysis, competition would require some value-added proposition, some form of better quality. In classic market theory, consumers would switch to the better product. About a third of markets have only one dialysis center; where there are more than one, transportation, especially with disability and comorbidities, is a more salient consideration than quality. Dialysis patients are "geo-locked" by these factors to specific centers. There are scheduling difficulties; dialysis takes up half the day, and while offered from 6 AM until 10 or 11 PM – you don't always get the schedule you want. Only 1.3% of dialysis patients change centers.

As it turns out, the most significant change with consolidation was standardization. The big companies put their established care protocols in place at the acquired centers, leveling that playing field. It is idyllic until you consider that standards are not always good; some standards are more suited to the factory floor than patient care.

Consider the changes to the acquired centers based upon the new standards for labor and capacity.

- 17% reduction in RNs, a 7% increase in less skilled (and less costly) dialysis technicians resulting in the patient to employee ratio increasing by about 12%.

- 10% increase in dialysis stations resulting in more patients serviced at one site

- The result, a lower cost to perform dialysis for which they were receiving a fixed payment. Economically, an improved margin.

The other standardization by the big firms was in the use of erythropoietin stimulating drugs, specifically Epogen, and secondary medications containing iron.

- Epogen use increased while at the same time, economies of scale lowered the purchasing cost. While Medicare reimbursements were on a price + calculation, the decline in individual payments was counterbalanced by greater use.

- The iron medications were priced at almost identical per mg costs. One brand, Venofer,

came in a 100 mg vial, the other, Ferriecit, in a 62.5 mg vial. Medicare paid by the vial, on that cost + basis, so the big firms' standardized care to the larger container, more to throw away, but a far bigger +. Once again improving their bottom line. Here is a graph showing the switch to the more expensive Venofer. A pretty dramatic example of the effect of standardization.

- The standardization to a more expensive drug was responsible for much of the acquired centers' more significant payments – a 7% increase from payments before their acquisition.

Patient outcomes

Now all of these standardizations would be acceptable if patient outcomes improved. Let us start with the good news, those URR rates, the measure of how well the blood was cleansed, improved by 2.1%. [2] With the good news out of the way, let's consider those other outcomes.

- Given the increasing use of Epogen, there was a 5% decrease in the likelihood that patients were in the acceptable hemoglobin range, a 10% increase in levels exceeding the recommendations.

- Hospital admissions for septicemia increased by 10%. Now whether this was due to poorly trained technicians or a need to turn over the station is purely conjecture. But something in the sterile technique changed. [3] There was also a small, not statistically significant increase in strokes and heart attacks, certainly something we might expect when hemoglobin levels were too high.

- One year survival for these patients decreased by 1.7%, at two years it had fallen by 2.9%

- At one year, new patients in these acquired facilities were 8.5% less likely to be a recipient of a transplant or even on a transplant waiting list. And these patients were no different; the only change was the standards manual brought by the big firms.

"When considering the totality of our results for clinical outcomes, hospitalizations, transplants, and survival, the overarching finding is that acquisitions result in worse care for patients."

Why didn't the independent firms imitate the more profitable chains?

The independents had the same tradeoffs to consider, how can you lower your costs and increase your profitability. The greatest disparity was in the price of Epogen and iron supplements. The independents didn't have the economy of scale to get substantial discounts. How does that old saying go, "the enemy of small business is big business." Besides, independents didn't have what malpractice lawyers were term "deep pockets."

"Chains may be more willing than independent facilities to accept this [malpractice] risk if they have large financial reserves to pay for any future litigation, allowing them to behave in ways that increase their profits even if it makes it more likely they will face malpractice lawsuits. Perhaps reflecting this, DaVita has made at least four settlements exceeding $100 million in the last 10 years."

The changes in dialysis care were driven not by consolidated markets, a problem that is addressed by our antitrust statutes. It was driven by those standardization manuals, that standardize care to take advantage of disparities in Medicare payments. Many of those disparities have been addressed. Since 2011, those costly drugs have been bundled into the payment for dialysis treatment. But that certainly doesn't guarantee that other small payment differences will not be exploited. And you should take this study as a parable for other areas in healthcare. The current fight over the site of service with differential and higher payments to hospitals is no different economically than the standardization by the large dialysis consortiums. I will let the researchers have the last words.

Changes in ownership affect the treatment and outcomes of patients at independent dialysis facilities acquired by chains. Our results show that acquired facilities change their behavior in three broad ways, each of which either increases their revenue or decreases their operating costs. First, acquired facilities capture higher per-session reimbursements from Medicare by increasing drug doses and shifting to more- lucrative drugs. Second, acquired facilities stretch their resources by treating more patients relative to the number of staff and stations at the facility. Third, acquired facilities reduce their costs of providing dialysis by replacing high-skill nurses with lower-skill technicians.

Adopting the acquirer's strategies causes the acquired facility's quality of care to decline. Along almost every dimension we measure, patients fare worse at the target facility after acquisition, most prominently in terms of fewer kidney transplants, more hospitalizations, and lower survival rates.

[1] During the period of the study, several large companies were also acquired by the two remaining firms. Their patients were not considered in this analysis, which was directed more at how a fragmented cottage industry was impacted by consolidation. The other highly fragmented cottage industries associated with healthcare are free-standing hospitals and independent physician practices. Both have been affected by this form of consolidation, what the researchers called a "roll-up" or "whale eats krill" strategy where large firms increasingly acquisition by a large company.

[2] Chair time is how long a patient is in the dialysis station, being hooked up to the machine, the period of dialysis, and being safely disconnected. Of the three components, the time on dialysis can be most easily adjusted. The faster the blood moves through the system; the quicker impurities are removed - faster flow rates will allow better dialysis even over shorter time frames. Of course, there is a tradeoff because faster flow rates require better access to the bloodstream – a topic for another day. Let us say that shorter dialysis times have costs, human and financial.

[3] This reliance on sterile technique to connect and disconnect a patient from a dialysis machine is one of the undiscussed hurdles in the administration's effort to have more dialysis done at home. Many of these patients and spouses have visual and motor problems, making the connection to dialysis more difficult than one might anticipate.

Source: How Acquisitions Affect Firm Behavior And Performance: Evidence From The Dialysis Industry Quarterly Journal of Economics DOI: 10.1093/qje/qjz034