Many natural remedies do not work. Despite those who swear by herbal medicines and other traditions that stretch back, in some cases, thousands of years, modern science often cannot verify the claimed benefits. But that isn't always the case. Occasionally, scientists confirm that a traditional remedy indeed does work, and one such example has been reported recently in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

Native Americans who burned sweetgrass (Hierochloe odorata) tended to do so for ceremonial purposes. However, some had a more practical use in mind. Two groups of Native Americans, the Flatheads of Montana and the Blackfoot of Alberta, used sweetgrass as an insect repellent. They did so by burning the grass and allowing the smoke to saturate their clothing or by placing sachets (scented bags) of sweetgrass in their clothing. It worked, and now a team of chemists knows why.

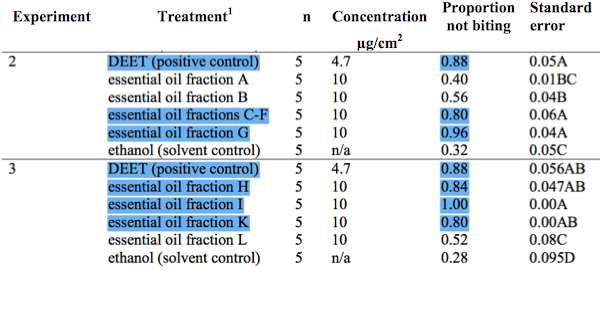

Oils were chemically extracted from sweetgrass. Next, the team tested how well these oils repelled mosquitoes. To do so, they tempted mosquitoes to "bite" through a cloth on the other side of which was a feeding solution. The cloth, however, was covered with sweetgrass oil extracts, and the researchers counted how many mosquitoes were deterred from feeding.

As shown above, DEET (a common mosquito repellent) served as a positive control, and it prevented 88% of mosquitoes from biting. Many of the sweetgrass oil extracts, which were applied at roughly twice the concentration as DEET, were every bit as effective at repelling the bloodsuckers.

The authors then subjected the most potent oil extracts to further molecular analysis. They identified three major molecules that mosquitoes found unpleasant: 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol, phytol, and coumarin. When these pure compounds were tested against DEET, they were not as effective. This suggests that the extracted oils contain other minor compounds that increase their potency.

It should be noted that just because these compounds are "natural" does not mean that they are safer for human use than DEET. Further toxicology research would need to examine that. But kudos to the researchers who, in a single paper, simultaneously advanced the field of anthropology and discovered a potentially commercializable product.

Source: Charles L. Cantrell, A. Maxwell P. Jones, and Abbas Ali. "Isolation and Identification of Mosquito (Aedes aegypti) Biting-Deterrent Compounds from the Native American Ethnobotanical Remedy Plant Hierochloë odorata (Sweetgrass)." J. Agric. Food Chem. Published online: 15-October-2016. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01668