The Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) is really stretching the word "medical" with some of their latest content.

A recent article, "As Opioid Epidemic Rages, Complementary Health Approaches to Pain Gain Traction" written by Jennifer Abbasi, highlights the role of complementary medicine in pain management, while focusing on which techniques may be more useful for particular ailments. Ms. Abbasi summarized and highlighted the findings of a large study published in September in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings that analyzed the use of complementary medicine for recurring pain that may become chronic or debilitating.

But, when you dig a bit deeper, the conclusion of the article is a stretch, at best.

The original study was done by a group of five people at the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. The authors have many varying degrees from distinct backgrounds ranging from a cardiologist to a naturopath. From a chiropractor to a PhD in neuroscience. The findings of the article were covered in depth by Dr. Kedist Tedla of ACSH in September, after the study was first published.

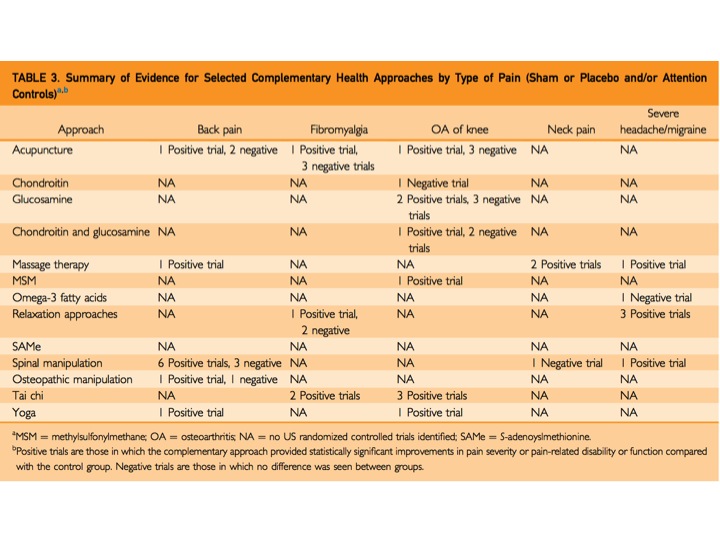

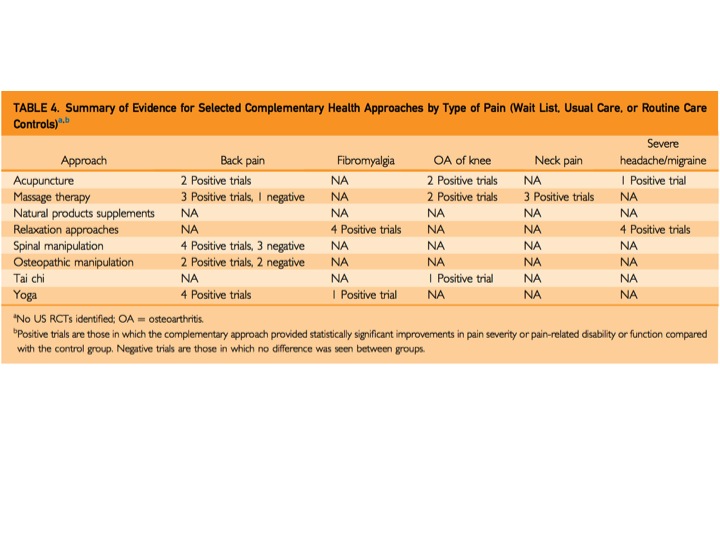

To summarize, the article looked at complementary health approaches to pain management, focusing on acupuncture, manipulation, massage therapy, relaxation techniques including meditation, selected natural product supplements, tai chi and yoga. It analyzed trials of these approaches by giving each a mark of "positive" meaning the technique was helpful or "negative" - not helpful. And, if there were more positive result than negative - the technique was deemed useful overall.

From this ridiculous rubric, they report the following to be helpful: acupuncture for back pain and osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee; massage therapy for neck and back pain; osteopathic manipulation for back pain; relaxation for headaches, migraines, and fibromyalgia; spinal manipulation for back pain; Tai chai for osteoarthritis of the knee and fibromyalgia; and yoga for back pain.

The first problem in making these large, generalized statements is the limitation of the data presented in the paper. The two tables that are responsible for these conclusions are shown below. Ms. Abassi's article highlights that acupuncture is helpful for back pain. However, Table 3 shows one positive and two negative trails in that category and Table 4 has two positive trials. In total, three positive and two negative trails. How does that conclude that acupuncture helps back pain? The rest of the 'supporting data' look just as murky. For spinal manipulation and back pain, there are 10 positive trails and six negative (SIX negative) but it is deemed helpful. Acupuncture for OA of the knee has three positive and three negative results. But, it is listed as a helpful therapy. That's 50/50!

As someone who has never experienced real pain (with the exception of the very real - but very fleeting - pain of childbirth), I have a hard time accepting that yoga or massage could make that big of a dent for someone who is experiencing true, chronic pain. People who suffer from chronic pain cannot be cured by a few chaturangas. But if they can, they did not have pain - they had mild discomfort.

Even though the study is lacking, it is the fact that this study got picked up, written about, and highlighted in JAMA that is disturbing. In publishing their summary of the paper, they are bringing more attention to a study on complementary medicine that is incredibly flawed, perpetuating the ongoing movement of giving these techniques more credibility than they deserve.

Dr. David Spiegel, the medical director of the Center for Integrative Medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine says, “I don’t think we’re at the point where it’s an obvious science yet, but I think we’re heading in that direction.” I think that JAMA should read that line again. If they are publishing articles highlighting approaches that are not backed by science, medicine is going down a very dangerous road. And, JAMA is leading the way.