The World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) recently concluded that the popular artificial sweetener aspartame, widely used in foods and diet drinks, is “possibly carcinogenic to humans,” an alarming conclusion because aspartame is used in thousands of low-calorie products. However, another WHO organization, the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), concluded that it is safe to consume aspartame. Can we make sense of the conflicting conclusions?

IARC classifies substances’ hazard, whether the substance can cause cancer – not reflecting the risk based on exposure level. The JECFA evaluates risk, the likelihood that cancer will occur because of exposure to a substance. These two approaches contribute to the differing conclusions of the two organizations.

IARC

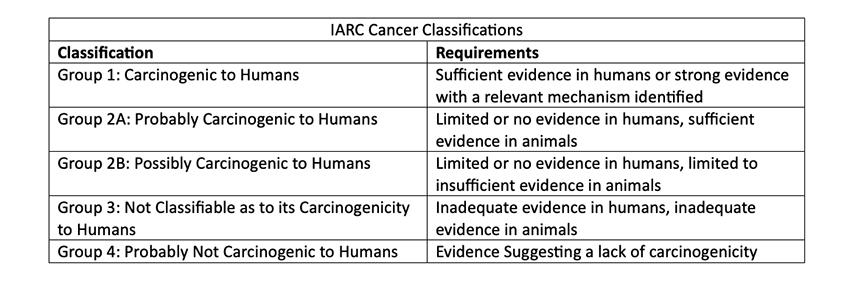

IARC began classifying substances in 1971 and has categorized over 900 substances. In 52 years, IARC has classified only one substance in Group 4, probably not carcinogenic to humans. The substance, caprolactam, used in manufacturing synthetic fibers, was moved by IARC to Group 3 in 2019.

IARC began classifying substances in 1971 and has categorized over 900 substances. In 52 years, IARC has classified only one substance in Group 4, probably not carcinogenic to humans. The substance, caprolactam, used in manufacturing synthetic fibers, was moved by IARC to Group 3 in 2019.

IARC has classified aspartame as Group 2B, possibly carcinogenic to humans.

Limited evidence for cancer in humans, specifically for liver cancer.

Three studies were the basis for this conclusion:

- A European study found that consuming more than six cans of soft drinks per week was associated with a higher risk of liver cancer compared to consuming no soft drinks. However, out of roughly 500,000 participants, there were only a small number of cases of liver cancer (191), and the study does not show that the aspartame in soft drinks caused the cancer.

- A US study examined the association of sugar- and artificially-sweetened soft drinks with liver cancer in diabetics and non-diabetics and found no association in non-diabetics but a significant association in people with diabetes.

- Another US study examined the association of artificially sweetened- soft drinks with mortality from all types of cancer. An association was noted “for cancers associated with obesity,” colorectal and kidney cancer, with no association for overall cancer mortality.

Limited evidence for cancer in animals

- The majority of animal studies have not shown an association between aspartame and cancer, including a study by the US National Toxicology Program (NTP), the premier government agency carrying out toxicological research, that reported no evidence of carcinogenicity in mice fed aspartame for two years.

- IARC based its conclusion of “limited evidence” on discredited studies in rodents from the Ramazzini Institute. The Ramazzini Institute has repeatedly been criticized for its lack of quality control. As I previously wrote, the EPA and other agencies no longer use Ramazzini Institute data in their assessments.

IARC concluded that “chance, bias, or confounding could not be ruled out with reasonable confidence in this set of studies.” Thus, the evidence for a link between aspartame and cancer was “limited” for liver cancer and “inadequate” for other cancer types.

Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA)

JECFA is an international scientific expert committee administered jointly by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and the WHO. They have been meeting since 1956 to evaluate the safety of food additives and contaminants and have assessed over 2500 food additives and over 40 contaminants.

JECFA examined the same studies as IARC for aspartame and concluded that

“the evidence of an association between aspartame consumption and cancer in humans is not convincing.”

They determined that there was no reason to change their previous conclusion that a daily intake of aspartame at levels up to 40 milligrams per kilogram body weight would not cause adverse health effects, including cancer. The FDA limit is slightly higher at 50 mg per kilogram body weight. Since a 12-ounce diet soft drink typically contains 200 – 300 mg of aspartame, an adult weighing 184 pounds could drink 11-16 cans a day and stay within this limit.

FDA

The FDA first approved aspartame in 1974 and has reapproved and expanded its’ uses several times. The FDA has examined and continually reassessed hundreds of studies on the safety of aspartame. FDA scientists do not have safety concerns when aspartame is used under its approved conditions. As they wrote in their response to IARC

“Aspartame being labeled by IARC as “possibly carcinogenic to humans” does not mean that aspartame is actually linked to cancer. The FDA disagrees with IARC’s conclusion that these studies support classifying aspartame as a possible carcinogen to humans. FDA scientists reviewed the scientific information including in IARC’s review in 2021 and identified significant shortcomings in the studies on which IARC relied.”

Flaws in IARC’s Classification

There are issues with IARC’s classification procedures that extend far beyond aspartame. Scientists have focused on the fact that IARC has only classified one substance as Group 4, probably not carcinogenic to humans (and then removed it from this group).

A study of 100 substances classified by IARC as Group 3 (not classifiable as to their carcinogenicity to humans) revealed that 24 of these substances met the criteria to be classified as Group 4. The authors concluded,

“The results of this analysis demonstrating that a significant minority of agents classified as Group 3 do not possess evidence of carcinogenic potential suggests that the absence of agents classified as Group 4 is due at least in part to a reluctance on the part of IARC committee members to designate agents as probably not carcinogenic to humans.” [emphasis added]

It is exceedingly unusual for the FDA to publicly disagree with another agency's conclusions. I commend the FDA for criticizing IARC’s classification of aspartame and standing behind their scientists' findings.

Hazard assessment is challenging, but when done correctly, it can add value; however, IARC’s classification requirements are so general as to be meaningless – other than to provide a new “class action” to lawyers ecstatic over this latest flawed conclusion. What IARC has done is a form of scientific disinformation, and the WHO is complicit in not resolving the conflict between its two organizations.