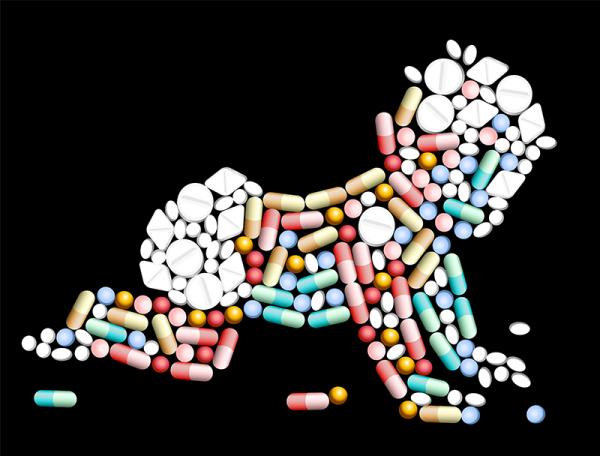

Babies inside the womb, as they exit and once out into the world —especially if breastfed—are influenced to varying degrees by their mother’s exposures, albeit illicit or prescription drug intake, food ingestion or smoking, to name a few.

If a pregnant mother is chronically using opioids, for example, then birth with subsequent severing of the umbilical cord enacts an abrupt cessation of the substance to the baby. The result is a newborn in withdrawal. This is called neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). It can be mild or happen upon a wide array leading to severe.

A new research letter in JAMA Pediatrics claims, “Incidence rates for NAS and maternal opioid use increased nearly five-fold in the United States between 2000 and 2012” and concludes from their interpretation of available data “the incidence of NAS and maternal opioid use in the United States increased disproportionately in rural counties from 2004 to 2013 relative to urban communities.”

What pregnant mom gets, baby gets to some extent. The magnitude and impact depends on the material itself, the dose, the half-life or metabolism of said item, duration of intake and temporal phase of pregnancy and delivery and, of course, the individual involved. Babies exposed to opioids in utero and with NAS can have any range and intensity of the following: jitteriness, low birth weight, irritability, poor feeding, seizures, difficulty gaining weight, inadequate suck, breathing issues, impaired sleep, vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, fevers, excessive crying, fussiness, hyperactive reflexes, prematurity, birth defects.

Babies commonly do well especially if the abuse is known prior to delivery, but they typically require a prolonged hospital stay and close observation in the newborn period. Long term effects are unpredictable and determined as the baby grows and develops which can prompt tremendous anxiety.

It is always essential to be assured opioids —or whatever the substance of abuse is— are acting in isolation. Multi-drug abuse is quite common. Where one is, often others follow and those need to be managed differently in the newborn.

The recent publication used 2004-2013 data of all neonatal and obstetric deliveries from the National Inpatient Sample compiled by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The sample represents hospital discharges of all-payer types.

Their results: “Compared with their urban peers, rural infants and mothers with opioid-related diagnoses were more likely to be from lower-income families, have public insurance, and be transferred to another hospital following delivery.” Rural infants with NAS increased from 12.9% in 2003/4 to 21.2% in 2012/13. From 2004-2013, NAS increased in rural infants from 1.2 to 7.5 per 1000 hospital births and 1.4 to 4.8 per 1000 hospital births for urban infants. During the same time frame, hospital deliveries complicated by maternal opioid use rose from 1.3 to 8.1 per 1000 hospital births for rural mothers and 1.6 to 4.8 per 1000 hospital births for urban mothers.

Both trends are disturbing and warrant intervention. This is a national and pan-cultural problem in need of multi-faceted and multi-disciplinary understanding and mediation.

The data is no panacea given coding changes can play a role as could changes in co-morbidity awareness or deliveries outside of hospitals, pre-naming urban vs rural and so forth. But, the increasing trend in rural and urban communities of opioid use and abuse can’t be ignored or denied.

The outcome of the work is highly relevant. Policy initiatives tailored to respective communities would likely procure more success than one-size-fits-all band-aids.

So, like most medical conditions and issues there is great regional disparity, hence the du jour trend of entitling it “population health.” A practice comprehensive and thorough physicians always employed prior to such formal naming. Understanding the complexities of a disease state—especially one as expansive as addiction— involves exploring the individual’s health and physical examination, environment, occupation, education, community, socioeconomic influences, genetic, personal habits, social interactions, living environment, family history, life and childhood history, phenomenology or biopsychosocial spheres.

This approach to combating and moving the needle on curing addiction with policies will be the only one that attempts to make a dent. A universal understanding that the mere existence of an opioid is not the sole cause of abuse and addiction is vital to compelling true change in those suffering. This issue is one of families and a societal ill that extends well beyond the individual abuser. It is not mutually exclusive to recognize this and still demand personal responsibility and accountability be taken when such abuse occurs.

Nevertheless, the cycle in families of the adverse effects of toxic extreme stress (e.g. extreme poverty, abuse) and managing adequately those issues as they arise is vital to a child’s acquiring resilience and effective coping strategies to avoid the need to self-medicate in adulthood. Addiction is often accompanied by co-morbidities. This is a notion necessitating nuance. Every child who experiences this will not necessarily become an addict, just as every addict doesn’t always have this background. But, many do. (1)

A parent’s suffering is a child’s suffering. Both lives are worth the effort. Our directives must address the symbiotic relationships that perpetuate the current and intergenerational struggles of families.

Notes:

(1) To review my work on the adverse physical, medical and mental health effects of childhood toxic extreme stress on adult development of disease, read President-Elect Donald & Melania Trump Put Son Barron First!, To Avoid Adult Dysfunction, Start 'IN UTERO', ‘Is Anthony Weiner a Sex Addict?’ is the Wrong Question, Pessimism Kills...Slowly.