In multiple studies, lower socioeconomic status (SES), the American term for caste, has been associated with poor health and treatment outcomes. Numerous factors drive those observations from the biological, i.e., elevated “stress responses in the sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis,” and more socioecological factors, i.e., education, income, employment, and access to care. Disentangling the biological from the socioecological is difficult on the best days, Sisyphian on the worst. A new study in PNAS takes a new approach and should give us room for thought.

Bone Marrow Transplantation

The researchers looked at individuals donating and receiving allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), a procedure most often performed for individuals with cancer of the blood, bone marrow or patients with immune deficiencies. The recipient’s blood-forming cells are first destroyed by radiation or chemotherapy. The donor’s blood stem cells are then concentrated and infused into the recipient. Overall outcomes range from significant disease-free life extension to cure. Because it can be associated with significant risk, HCT is reserved for life-saving situations.

The researchers posed the following question,

“whether the SES of an HCT cell donor might affect the treatment outcomes of an HCT recipient (over and above the recipient’s SES and other known clinical or demographic determinants of recipient outcomes) and assessed whether SES-associated health risk was transferrable through the transplanted hematopoietic cell pool.”

The researchers looked back at just over 2,000 donor-recipient pairs in the Center for International Bone Marrow Treatment and Research database who had one of four types of blood-borne cancer over a 13-year interval. [1] 44% of recipients and donors were female, and more than 84% of donors and recipients were White. The median age of recipients was 51, and for donors, 34. A measure of socioeconomic status was derived using their addresses correlated with US census data for the zip code that characterized median household income, % of families living below the poverty level, % of population over 25 without a high school education, % of rental housing, and % unemployment for individuals over age 16. A more significant disadvantage, lower SES, resulted in a higher score.

I recognize that the data set is skewed, which may introduce bias and make the findings less generalizable. I also will concede that the researchers’ definition of SES is not necessarily the most definitive. But that is the data we have. You may apply as much uncertainty as you wish to their findings.

Results

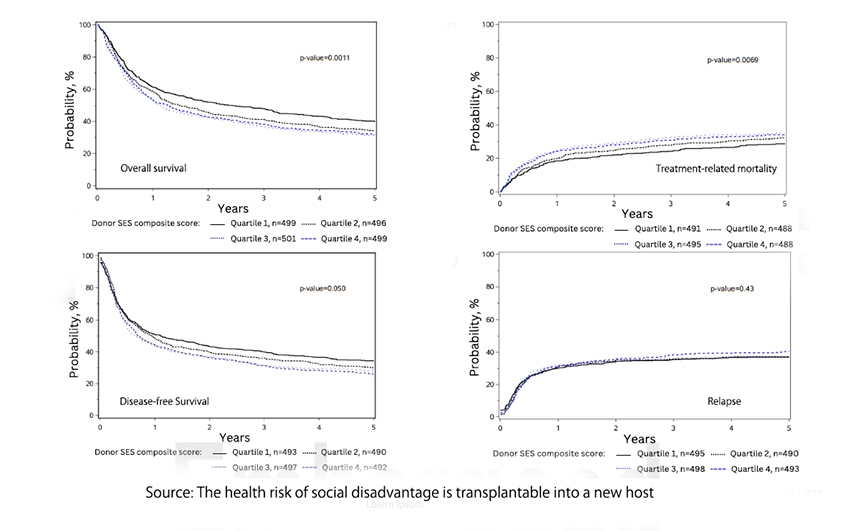

- Recipients receiving transplants from donors in the two lowest socioeconomic status (SES) quartiles had worse survival rates compared to those receiving transplants from donors in the highest SES quartile. At three years post-transplant, overall survival (OS) was 38.2% for recipients from the most disadvantaged SES quartile, compared to 47.9% for those from the highest SES quartile, a significant 9.7% difference.

- Recipients of transplants from donors in the two lowest SES quartiles had a higher risk of treatment-related mortality (TRM) compared to those from the highest SES quartile. At three years, TRM was 30.8% for recipients from the lowest SES quartile, compared to 24.2% for those from the highest SES quartile, a significant 6.6% difference.

- Donor socioeconomic status (SES) was significantly associated with recipient disease-free survival (DFS). Recipients of stem cells from donors in the lowest SES quartile had inferior DFS compared to those from the highest SES quartile, a significant 18% difference.

- Donor socioeconomic status (SES) was not associated with cancer relapse or the two most severe complications of HCT, acute and chronic graft-vs.-host disease.

- The socioeconomic status of the recipient has no impact on any of these clinical outcomes.

These findings were independent of the recipients' demographics of the recipients, socioeconomic status, and treatment characteristics. Taken together they

“confirm the notion that the biological impact of socioeconomic adversity penetrates molecular and cellular functioning, but that it is transferrable, with an influence sufficiently durable and robust to affect critical long-term health outcomes.”

The underlying mechanism of memory and transfer of these influences remains unclear. The familiar findings of stress response and inflammatory markers alterations have been associated with lower SES and provide at least one biologically plausible pathway for alterations in cell behavior.

The authors end on this note:

“Recognizing SES as a biological predictor, akin to clinical vital signs, could open opportunities for earlier interventions aimed at improving health outcomes and reducing health disparities.”

That is too reminiscent of the push to make pain the “5th vital sign” to make me comfortable, and it certainly runs counter to the increasing push to remove social constructs, like race, from the physician vocabulary. That said, increasing studies demonstrate that we inherit more from our parents than genes and that we can also inherit, in a biological sense, the good and bad of their life experiences.

[1] acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome

Source: The health risk of social disadvantage is transplantable into a new host PNAS DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2404108121