If you are ever in need of an impressive biological story, look no further than the examples of mutualism, when two totally unrelated species not only coexist, but both benefit from the relationship. One recently discovered example of this is particularly impressive.

In a new paper published in Cell, Drastic Genome Reduction in an Herbivore’s Pectinolytic Symbiont, the discovery of a new type of bacteria and the symbiotic relationship with its beetle host (the leaf beetle Cassida rubiginosa) is described.

This new bacteria, Candidatus Stammera capleta (referred to as simply Stammera) was named after Hans-Jurgen Stammer, an ecologist who made some of the first observations about this system in the 1930s. According to the authors of the work, Stammer wrote that, "unlike most leaf-eating beetles that he had studied, this one had sac-like organs that he had never seen before and the organs were filled with micro-organisms."

Now, almost one hundred years later, those micro-organisms have not only been identified but their role in the beetle is now understood.

Pectin is a class of a complex set of sugars (polysaccharides) that are present in most plant cell walls and are an abundant component in the non-woody parts of terrestrial plants. We happen to eat quite a bit of pectin in our diets. It is also produced commercially and is added to foods like jams and jellies, dessert fillings, medicines, sweets, juice drinks, etc - usually as a gelling or thickening agent and/or stabilizer.

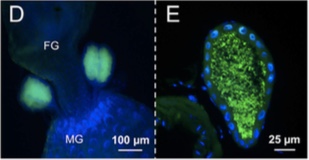

The linkages between the sugars in pectin are generally not easily broken down by enzymes. However, the enzymes that can degrade pectin, called pectinases, are found in two organs connected to the foregut of the leaf beetle. And, that is also where the Stammera lives. (1) This can be seen in the fluorescence microscopy below. The green represents the Stammera bacteria, seen on the left in the two areas that flank the foregut (FG). The micrograph on the right, which looks inside one of those organs, shows a dense population of the Stammera bacteria.

Not only that, but, the Stammera bacteria were found in 100% of C. rubiginosa beetles surveyed from New Zealand, the United States, Germany, and Japan. Usually, when a relationship is that consistent in nature, there is a good reason for it. The researchers discovered that Stammera provides the enzymes that give this leaf eating beetle the ability to digest pectin, and, to a beetle, that is a big deal.

Stammera is not just helpful to the beetle, it keeps it alive. When the bacterial pectinases degrade pectin, the beetle reaps the benefits, using the breakdown products as a source of energy. In order to understand just how important the bacteria are to the beetle, the researchers removed the Stammera from the beetle and showed that the bacteria-free beetle larvae did not survive as well than those who had Stammera.

In exchange, the Stammera not only get a place to call home, but also the assurance that they will be passed to future generations of beetles. The beetle has a built-in mechanism that entails topping their eggs with a small structure packed with Stammera, ensuring that bacteria will colonize the larva upon ingestion.

Even more interesting is the genetic composition of Stammera, or lack thereof. Stammera has the smallest known genome of any extracellular bacterium. The genome is 0.27 Mb or 270,000 DNA base pairs. Most bacteria have millions of base pairs in their genomes. But, size does not seem to matter here because even though the genome be but little, it is fierce. (2)

There are only 251 putative protein-coding genes in the bacteria, which is not a lot. The small genome of Stammera makes its pectin degrading abilities truly remarkable. And while the bacteria has genes for some of the basic functions needed to keep the cell alive, like being able to replicate its DNA and make energy, it is missing many basic genes that most other living organisms have.

This new paper highlights one of those symbiotic relationships found every now and then in nature that makes us marvel at just how spectacular the evolution of our biodiversity is.

Notes:

(1) The Stammera was also found in two glandular reservoirs opening into the female insect’s vagina

(2) Adapted from Act 3, Scene 2, Page 13 of A Midsummer Night's Dream, "And though she be but little, she is fierce."

References:

Source: Hassan Salem, et al. "Drastic Genome Reduction in an Herbivore's Pectinolytic Symbiont" Cell 10-Nov-2017. pii: S0092-8674(17)31251-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.029

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/11/171116132757.htm