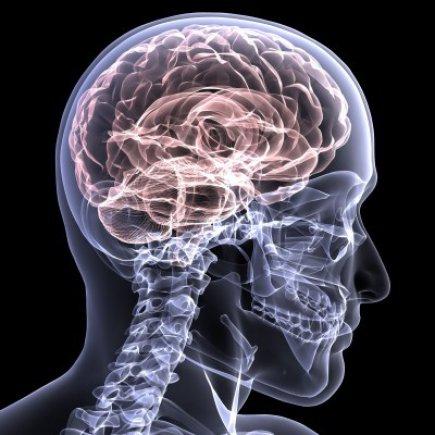

While it's now commonly felt that we need to minimize exposure to concussions as a way of preventing the onset of greater brain trauma in the future, what often goes overlooked is the impact of lesser impacts, known as microconcussions.

Starting with research into football and other sports-related concussions, valuable attention has been paid over the last decade to a resulting disease that is extremely debilitating: Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE. Valuable in the sense that revealing the causes of the cumulative effects of severe brain trauma can help us take steps towards preventing it. But an important by-product of that research reveals how microconcussions – hits to the brain that don't produce visible symptoms – can also add up to create trouble at a later date.

Results from a recent study focusing on brain differences between contact-sport athletes and noncontact-sport athletes were, for the most part, inconclusive. But as a result of their work, those researchers are appreciating the significance of these lesser brain impacts, which are also known as subconcussions.

"The verdict is still out on the seriousness of subconcussions, but we've got to learn more since we're seeing a real difference between people who participate in sports with higher risk for these impacts," states Nicholas Port, an associate professor in the School of Optometry at Indiana University. "It's imperative to learn whether these impacts have an actual effect on cognitive function – as well as how much exposure is too much."

As opposed to a full-on helmet smash, commonly seen on the football field that staggers the recipient or leaves him noticeably woozy, subconcussions occur, for instance, when players of any sport collide with some force (think hockey or lacrosse) or when soccer players head the ball.

CTE is a progressive, neurodegenerative disease caused by repeated hits to the head, resulting in brain trauma. It is common among athletes, football players chiefly among them, who both play contact sports or have a history of concussions. Confusion, memory loss, mood swings, depression and uncharacteristic aggression are some of the visible symptoms. CTE can only be detected post-mortem, but strides have been made to diagnose it in the living.

"Many people are surprised to hear that there have been cases of CTE discovered in athletes who have never been diagnosed with a concussion," states the Concussion Legacy Foundation, the country's leading research organization on brain trauma. "This revelation has spurred some scientists to look at other types of brain trauma as a possible cause of CTE."

"Many people are surprised to hear that there have been cases of CTE discovered in athletes who have never been diagnosed with a concussion," states the Concussion Legacy Foundation, the country's leading research organization on brain trauma. "This revelation has spurred some scientists to look at other types of brain trauma as a possible cause of CTE."

And coming from CLF researchers, whose work has greatly altered the National Football League's approach to player safety, as well as the perspective of the U.S. military, and science's overall understanding of this disease, that is significant.

And so it this sobering statement.

"Currently, the best available evidence suggests that subconcussive impacts, not concussions, are the driving force behind CTE."

As a result, the Foundation recommends that whatever steps can be taken to minimize hits to the head – by delaying when young kids start playing contact sports, and/or altering rules wherever practical to limit contact – will lessen the risk of future head trauma. As we are learning, it appears that every little bit of prevention counts.