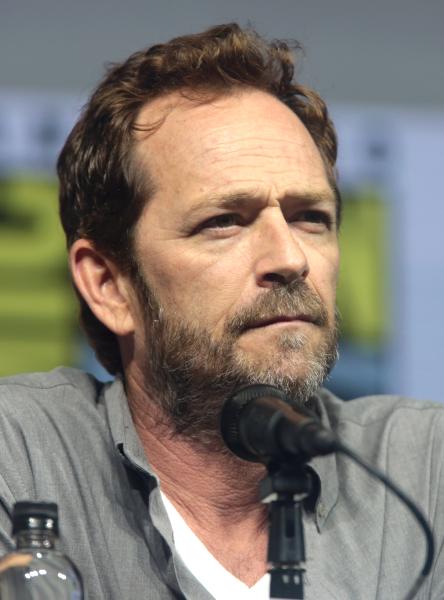

With the tragic death of beloved actor Luke Perry of television’s Beverly Hills 90210 and Riverdale fame secondary to last week’s reported “massive” stroke, the topic of such a catastrophic event for a 52-year-old man to endure is now prevalent in the public sphere. As well it should be. There are many misconceptions about strokes that warrant clarification, vastly ranging from who is at greatest risk to what is the likelihood of recovery.

Let’s tackle some of the lingering questions on the subject here.

Is there a standard, uniform recovery after a stroke?

The length of recovery is directly related to the extent of the injury and proximity to vital structures. The brain and brainstem are among the most premier real estate in the body. Location, location, and location guide whether the consequence is short- or long-term disability or death. A person’s underlying individual clinical status and accompanying medical conditions play compounding roles.

Recovery depends on what you are referencing. Restoration of blood flow is a physiologic, earlier process and reasonable marker but it doesn’t necessarily tell you whether the patient will regain normal functioning and thrive - such recovery takes longer if it all.

How does the severity of the stroke and the region that was affected play a role?

These factors are of singular importance. A catastrophic stroke within the brainstem, for example, can be life-threatening as it imperils involuntary breathing, consciousness and an ability to regulate blood pressure. Recovery in this scenario depends on where the damage is within the brainstem and whether treatment was rapidly received and effective. Strokes in other regions of the brain can result in loss of sensation and motor function, speech and language issues to behavioral problems, for instance. Emotional effects as well as impaired judgment can result. Strokes occur in a wide array from minor to severe and the deficits correspond to geography and response to treatment.

How long is the critical phase?

This is highly variable and individual dependent. For some patients, they can begin rehab within days and others might require weeks to months. There are different types of strokes and the etiology matters (e.g. hemorrhagic versus ischemic). Hemorrhagic strokes involve a bleed from a ruptured aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation (AVM), for example. This irritates the brain and does meaningful harm. When blood remains within its intended conduit, it acts to nourish organs and delivers oxygen. When it leaks or bursts outside of the housing vasculature, it damages surrounding structures. An ischemic stroke involves the opposite mechanism where brain tissue gets starved of oxygen due to something impeding blood flow like a blood clot. Damage occurs through deprivation.

Critical periods follow unique clinical courses depending on the source of the problem and the factors previously mentioned. When aneurysms rupture, for instance, the immediate issue might be to stop the bleeding and prevent dreaded re-bleeding while needing to manage intracranial pressure. Then, there is concern as peak cerebral vasospasm can occur a week out of the initial event causing profound delayed morbidity and mortality. This undesirable secondary effect causes neurologic deficits by delayed ischemia from narrowing of a cerebral blood vessel. So, someone can survive the big event and surgical intervention, then endure complications as the natural course of the injury unfolds.

When it comes to rapid treatment for ischemic strokes, they are shooting for about an hour door to needle (for clot-busting drugs) within a 4 hour window of the start of symptoms. The vascular bed of the brain is very redundant and often time ischemia in one area is associated with a penumbra that improves over a few hours to days. For hemorrhagic strokes, the goal is to control bleeding and reduce intracranial pressure that can hurt the brain further - depending on the cause surgical intervention may be necessary.

Who is at risk? Are there ways to prevent strokes?

Anyone can have a stroke, albeit an infant to otherwise healthy adult. But, the risks increase as we age. The causes are highly variable ranging from genetic predispositions, trauma, medications and vascular malformations to blood clots, underlying disease (e.g. diabetes) and clogged blood vessels. Smoking, high cholesterol and high blood pressure enhance risks, for example. Living an active healthy lifestyle is a great first start to managing chronic disease and, hopefully, avoiding it entirely. To learn what influences can and cannot be controlled, review the American Stroke Association materials here. Also, seeking treatment swiftly when warning signs appear can heavily factor into long-term survival. (See here for symptoms).