Before jumping into the study, it might be instructive to consider the origins of both the Castle Doctrine and Stand Your Ground (SYG). To do that, we must return to merry Olde England in the 1600s. Starting at least a century earlier, the open common lands of England became increasingly privatized. The land was enclosed (fenced), often, but not always, by informal agreement. Of course, one man’s informal agreement is another man’s seizure. The idea of a man’s home being his castle comes from one side of that disagreement and allows a defense of one’s home, in this case preventing the enclosure of your land by another. This was the origin of the Castle Doctrine.

Of course, those now on the short side of the bargain felt that they might take matters into their own hands without the need to await adjudication. You might call it self-help; those on the receiving end might call it vigilantism. But this resulted in another common law, the duty to retreat. Faced with a confrontation, the two sides had a duty to retreat and let the courts resolve the problem. Common law provided two distinctly different, even contradictory approaches; case law would determine when one was more pivotal than the other. Both ideas, along with the English colonists, came to America.

America, too, had its period of enclosure in the mid-1800s. It is easy to see how Manifest Destiny and our westward expansion would emphasize the right to defend over the necessity to retreat – the land grabs in the West were not always based upon deeds, as much as the squatter’s possession. Today, despite its origins concerning disputed property, the Castle Doctrine is now an affirmative defense, mitigating the consequences for individuals charged with criminal homicide in the protection of their homes.

This came about in 1985 when Colorado passed the first “Make my day” [1] laws shielding individuals from criminal or civil liability for using force against a home invader, including deadly force. Like the immunity granted to law enforcement, the individual must feel threatened with bodily harm or death and may not have provoked the intruder’s threatening actions.

The definition of “home” has expanded over time. First to our cars in the 1930s when questions were raised about searches of cars during traffic stops. (More on that can be found here.) More recently, it has been applied to our “personal space,” allowing a Castle Doctrine defense to shootings in parking lots. I would argue that equating personal space with our homes goes too far. In most instances, we invoke personal space in common areas, public or private.

In States where the Castle Doctrine is in effect, there is no duty to retreat; you may “stand your ground.” The first law to explicitly state this was in Florida in 2005. [2]

The question we must ask and answer is whether these policies, enacted as laws, are protective. A Rand analysis points out that SYG lowers the bar for using lethal force in self-defense and should, if effective, lower crime rates or switch criminals to less risky crimes. On the other hand, criminals, knowing that homeowners are potentially armed and legally "safe," may choose to arm themselves too, inadvertently increasing the use of firearms in homicides.

“To disentangle these mechanisms, the ideal analyses would distinguish between the effects of stand-your-ground laws on criminal violence and the effects on violence committed in self-defense.”

In their analysis, subsequently updated to 2020, Rand found evidence that SYG might result in more violent crime. They found no evidence for any of the other seven outcomes they considered. [3] In short, SYG increases firearm homicides. A new study takes another look Like the Rand study disentangling “criminal violence and the effects on violence committed in self-defense” remains problematic at best.

The current study

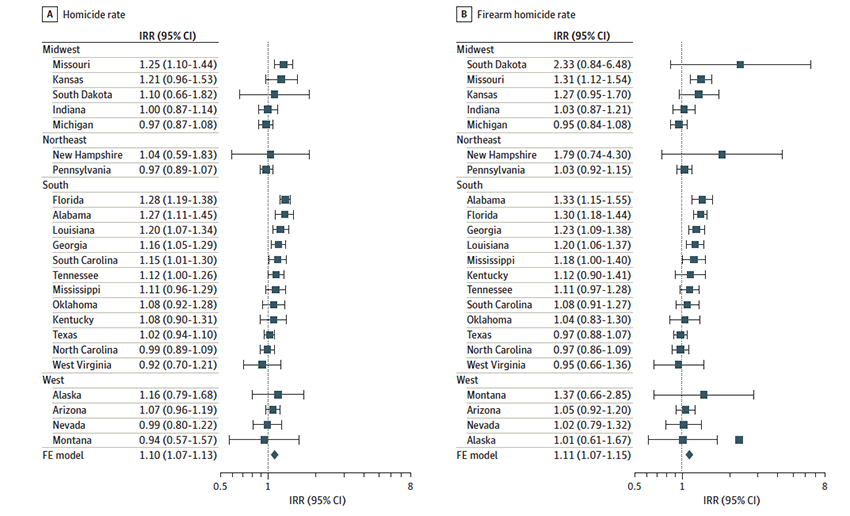

The researchers defined an “SYG law as a legislative statute that extended the legal right to use lethal force in self-defense to anywhere the individual has the right to be.” They identified 23 SYG states and 18 states serving as the controls (most with Castle Doctrine legislation). [4] Causes of deaths were based on coroner findings from 2000-2016. Deaths by suicide acted as a “control” for firearm violence in general.

- SYG had no impact on overall firearm violence as measured by suicide or firearm suicides

- Race, age, and gender of homicide deaths were unchanged, although the most significant increases were found for “White individuals and for males.”

- The enactment of SYG laws was associated with 7.8% more homicides and 8% more firearm homicides nationally. These rates were higher in the SYG states, 9.9% and 10.8%, respectively

Those national statistics would suggest, as did the RAND study, that SYG laws might increase violent crimes and not be as protective as some of its proponents would argue. More importantly, that national aggregated number hides the significant variability among the states in homicidal deaths. More specifically, the enactment of SYG laws increased homicide and firearm homicide by 16-33% in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Missouri.

The bottom line is that SYG did not demonstrate a reduction in crime, nor did it demonstrate significantly more homicides in all states that enacted SYG laws. Why a handful of states have significantly increased homicides remains unclear and, as the researchers suggest, “is key to understanding how and why legally expanding the right to use deadly violence in public is associated with increases in homicides in some states.”

The bottom line is that SYG did not demonstrate a reduction in crime, nor did it demonstrate significantly more homicides in all states that enacted SYG laws. Why a handful of states have significantly increased homicides remains unclear and, as the researchers suggest, “is key to understanding how and why legally expanding the right to use deadly violence in public is associated with increases in homicides in some states.”

[1] The phrase comes from Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry movies; you can find the clip here.

[2] "A person who is in a dwelling or residence in which the person has a right to be has no duty to retreat and has the right to stand his or her ground and use or threaten to use: Nondeadly force against another when and to the extent that the person reasonably believes that such conduct is necessary to defend himself or herself or another against the other's imminent use of unlawful force; or deadly force if he or she reasonably believes that using or threatening to use such force is necessary to prevent imminent death or great bodily harm to himself or herself or another or to prevent the imminent commission of a forcible felony."

[3] Defensive gun use, restrictions on gun sales or regulations, mass shootings, suicides, unintentional injuries and deaths, officer-involved shootings, or hunting and recreation.

[4] SYG states - Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia

Non-SYG states - Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Rhode Island, Vermont, Wisconsin, Wyoming

Source: Analysis of “Stand Your Ground” Self-defense Laws and Statewide Rates of Homicides and Firearm Homicides JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0077