The term "fentanyl" has become synonymous with both pharmaceutical and illicit fentanyl as well as the two dozen or so analogs (1) that are being seized by the DEA (2) across the country. While not scientifically rigorous, for purposes of general discussion, the term is fine provided that one realizes that there is a range of potency (deadly to deadlier e.g. carfentanil) from one analog to the next. They're all bad but some are worse.

But, like heroin and morphine, fentanyl has one "redeeming" quality: There is a widely-known antidote called Narcan aka naloxone (3) that will usually save the life of one of the countless people who have become "fentanyl casualties," depending on the analog in question and the magnitude of the overdose.

Not so with the latest monster xylazine, aka Tranq, a "new-old" (4) drug that has made headlines this past winter, even though it has been abused in the US since the early 2000s. Now the drug is increasingly being found on the street and in the blood of people it has killed. In Philadelphia – one of the first cities (along with Puerto Rico) to be hit with the deadly drug – it has recently been detected in 91% of heroin and fentanyl samples, up from 2% in 2010-15. Additionally, 31% of blood samples when heroin and fentanyl were the cause of overdose deaths contained xylazine. In Massachusetts, the drug was found in 28% of all opioid samples.

Like fentanyl, Tranq is also a legitimate drug – for horses. I have previously written about how easy it is to make fentanyl and analogs. While this is true, this synthesis of Tranq is so short and so easy that you could juggle chainsaws while churning out huge batches in your kitchen. At the risk of driving away all five of you readers, I'm going to show just a little bit of chemistry to demonstrate my intellectual superiority how easy it is to obtain the materials and put them together. My apologies in advance for...

Steve (left) detects a malodorous emission. He accuses Irving, who takes offense, of expelling said emission. Irving is clearly not a student of irony, as demonstrated by his peculiar response.

Figure 1. The chemical synthesis of xylazine. Piece of cake.

Figure 1 (above) may look daunting but bear with me for a moment. The first take-home message is that the synthesis is very short – only three steps (yellow). Less obvious is that the chemicals required to make the drug are common, readily available, and inexpensive. Here are the approximate prices (per pound) charged by Sigma-Aldrich:

- 2,6-Dimethylaniline $88 (QUIZ: Does anyone know what else this is used for?)

- Thiophosgene $450

- 3-Aminopropanol $1200

Starting with one pound of 2,6-dimethylaniline the above synthesis will give you about two pounds (5) of xylazine for less than $2,000.

But that's all unnecessary, useless information

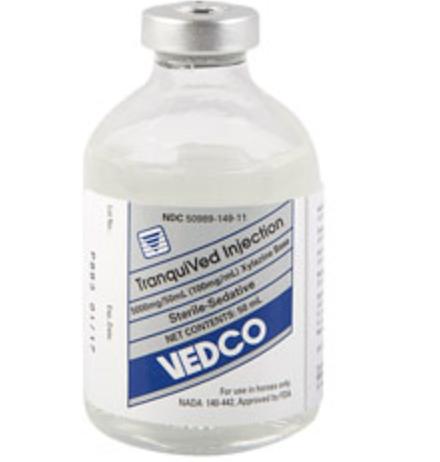

Why? Because it's probably not worth the trouble. Xylazine (brand names Rompun®, Sedazine®, AnaSed®) is approved as a sedative for veterinary use only. And it isn't even a controlled substance (!). You can buy it online (with a veterinary prescription) so why would anyone want to bother to make it?

Would someone kindly explain why the morons at the DEA are busy counting every tramadol pill, a very weak opioid, that a physician prescribes (assuming they dare do so) when you can borrow a neurotic dog (or a horse, a bit less convenient) and stroll out of the vet's office with a prescription and order the stuff online? Tranq can be diverted or made in illegal labs. Which is true? It really doesn't matter. The drug is readily available and killing people.

Is xylazine worse than fentanyl?

That depends on what "worse" means. The lethal dose of xylazine in humans is hard to pin down (partly because the drug is rapidly and irregularly metabolized) but it's clearly more than the 2 mg of fentanyl that will kill you. Xylazine is less dangerous when used alone. But this is not what's going on. Xylazine is typically added to fentanyl and heroin to cut them (and make both together more dangerous). It's safe to say that xylazine is less potent than fentanyl...

But...

Here's the bad news. Unlike opioids (opioid agonists) xylazine is an alpha-2 blocker; very few drugs operate by this mechanism. This means that Narcan won't do a thing. Nor will anything else; there is no antidote. Here is a list of adverse effects in humans.

- blurred vision

- disorientation

- drowsiness

- staggering

- coma

- bradycardia

- respiratory depression

- hypotension

- miosis (shrinking of the pupils)

- hyperglycemia

And this. Rotting flesh. I'm not posting these photos because they're too disgusting, but if you have a strong sense of curiosity (and stomach) knock yourself out. What causes the rotting flesh? See note #6.

Why?

Dr. Jeffrey Singer, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, ACSH advisor, and my frequent writing partner is on the right track. He has written about the "iron law of prohibition" – when a drug is banned it is usually replaced by one that is worse. Dr. Singer writes about the proliferation of nitazenes – opioid agonists that may be even worse than fentanyl.

News reports about the growing presence of nitazene among the mix of street drugs should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with what has come to be known as “the iron law of prohibition...An application of what economists call the Alchian Allen Effect, the concept was applied to prohibition (alcohol, cannabis, and other illicit substances) by Richard Cowan in the 1980s, who stated it simply: “The harder the enforcement, the harder the drugs.”

Dr. Jeffrey Singer in his Cato Blog

Just another example of the "Iron Law." And yet another failure.

Yet, our "leaders" (and also the corrupt scum that benefit from the opioid denial movement) fail to understand that, as Dr. Singer writes, that prohibition not only doesn't work, but it makes the problem worse. Does anyone understand this? Or care?

(1) Analogs are a series of "chemical cousins" of a particular drug or chemical. They are usually structurally and pharmacologically similar to the parent drug.

(2) Perhaps if the DEA spent less time breaking down doors to pain clinics run by honest physicians for exceeding BS quotas imposed upon them they'd do a better job of keeping the really dangerous s### off the street. Just speculating.

(3) Naloxone/Narcan is less effective in reversing a fentanyl overdose because fentanyl binds more tightly to opioid receptors. It is not uncommon that fentanyl overdoses sometimes require multiple doses of Narcan. And it doesn't always work.

(4) Xylazine is both old and new. It was first discovered in 1962, but its proliferation as a fentanyl additive is a new development.

(5) If you have to ask why don't ask.

(6) "I think the reason emergency rooms are seeing people with “rotting flesh“ is that people are falling asleep and remain asleep in one position since the drug is so powerful. That allows for pressure necrosis to set in— at least that’s what most clinicians are theorizing." Dr. Jeff Singer, private communication, 10/12/22