A recent study in JAMA Network Open sought to try and bring some organization to the syndrome of Long COVID. Their data came from a long-term academic study of COVID waves, the COVID States Project, an internet survey. Right away, it is clear that the underlying data will be self-reported and, as such, may be discounted. But when talking about symptoms, and that is what the study sought to identify, self-reporting is the norm.

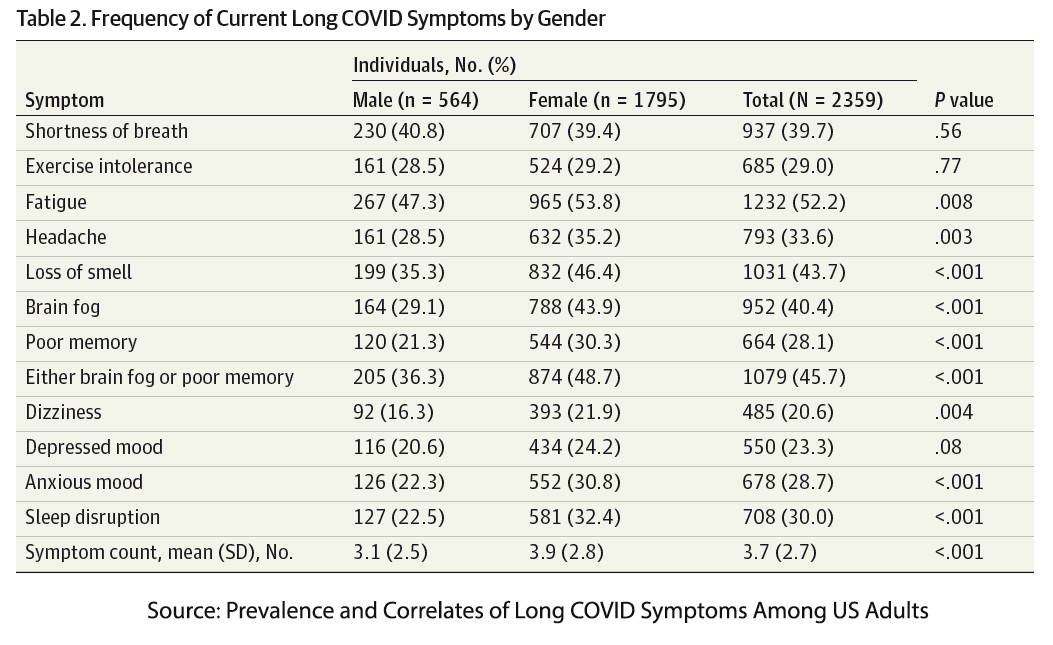

Roughly 16,000 participants reported having a positive COVID test (either PCR or antigen) two months or more proceeding the survey. 2359 or 14.7%, reported persistent symptoms. Here is how they breakdown

You can ignore that last column of p-values that refers to whether men or women are more inclined to have a particular symptom. Of course, if we had some numbers for these symptoms in the population without COVID, the more “diagnostic” might be identified. For example, the incidence of fatigue varies between 7 and 45%. In one study, fatigue was more noted among the younger age groups and women. Similarly, the CDC reports a 19% incidence of anxiety in adults, and again more common among younger individuals and women. According to the Sleep Foundation (and I will acknowledge their vested interest in a high percentage), 33% or more older adults experience insomnia, a sleep disorder.

Now I mention those rough baseline numbers not to denigrate the work of the researchers but to simply suggest that compiling a set of symptoms without considering the background may result in unintentionally biasing the data. If I had to hazard a guess, I would put my money more on shortness of breath and exertional intolerance as essential symptoms of Long COVID, but as I said, that would be a guess.

Here is another study of long COVID symptoms from the Annals of Internal Medicine. This NIH study compared 189 individuals with PCR-positive COVID with 120 relatively well-matched controls. (There were fewer mood disorders, including anxiety, among the controls). Here are their findings:

The second study seems more valid; at least we have a control that might reflect the baseline incidence of these symptoms in the general population. The study demonstrated no objective biological findings, “no evidence of persistent viral infection, autoimmunity, or abnormal immune activation in participants with PASC [Post Acute Sequelae of COVID or Long COVID].” The only findings noted, as identified by a critique of the study, which some may find politically and even factually incorrect.

“The only variables in patient histories and so on that correlated with a greater likelihood of showing PASC were being female or having a self-reported history of anxiety disorders, … A standard anxiety evaluation (GAD-2) showed a significant correlation between higher anxiety scores and reports of symptoms as well.”

Let me hasten to add that I am not suggesting that this is a modern-day version of “hysteria.” My sole contention is that we have yet to come to a consensus over what symptoms may be part of defining a Long COVID syndrome. And without a consensus on the definition, epidemiological counting of cases is plagued with significant uncertainty. We have to be able to define apples from oranges, and with Long COVID, we can’t, at least as yet. As an article in Nature points out, having a large dataset without a clear definition does not make our conclusions more accurate. Those studies are further confounded when using data from electronic health records, where standard definitions are, at best, an afterthought.

Scientific consensus takes time, ascertaining what is real or not real concerning Long COVID will take even more time, irrespective of the headlines or the chattering experts. Understanding this, will put the following study, and others like it, into perspective.

The Stigma of Long COVID – new victims

The study published in PLOS sought to develop a scale to ascertain the stigma encountered by individuals with Long COVID. The dataset came from online, and therefore, the self-reported experience of adults over age 18 who had COVID but had not been hospitalized. One year after enrollment, they went back to query participants on their experience of stigma from Long COVID. The stigma “instrument” they hoped to develop included 13 questions on experienced, internalized, and anticipated episodes of stigma.

There were roughly 1100 participants from the UK, 50% of whom had a “diagnosis” of Long COVID – of course, there is no consensus on the elements of that diagnosis, so this categorization is “premature.” Here are some of their findings; I have truncated the table to show the findings for the entire cohort, those with a “diagnosis” and those who “self-report” Long COVID.

If you look at the experienced, enacted stigmas, only “stopped contacting me” might be considered objective; all the rest are subjective experiences. Again, I hasten to add that I am not denying their experience; I am only suggesting that other factors may well color it. And those factors are made more apparent when we look at the internalized and anticipated stigmas – all of which reside in our minds, specifically the anxiety and depression of moods noted in the first two studies.

The prevalence of stigma noted in the study [1] lies on thin “scientific” ice. And that is alluded to in the researcher's report of limitations.

"Stigma is a non-pathological construct, and measurements do not have standardised diagnostic criteria. … and there is no agreed cut-off for measuring prevalence."

Neither Long COVID or stigma have standardized diagnostic criteria. That makes the statistical analysis a fantasy and the conclusions, at best uncertain. That none of this is to say that, as with other syndromes that may have a nuanced autoimmune basis that we, as yet, fail to appreciate, that Long COVID is real. But the state of the science at this juncture means that a healthy dose of skepticism is warranted for the scientific curious reader.

[1] For often or always, enacted stigma was reported by 75.9%, internalized by 25.3%, and anticipated by 59% of participants

Source: Prevalence and Correlates of Long COVID Symptoms Among US Adults JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.38804

A Longitudinal Study of COVID-19 Sequelae and Immunity: Baseline Findings Annals of Internal Medicine DOI: 10.7326/M21-4905