I have written about attempts to eat our way to health through more nutritious diets. For the most part, the impacts have been small, but a recent study in Nature asked whether we might not eat our way to health—could a sustainable program of fasting make a difference?

Fasting

In studying rodents, where we can measure aging and longevity, “everyday nutrition,” especially the amounts of protein and carbohydrates, can play a pivotal role. Additionally, providing our rodent pioneers with a limited window of time to eat as much as they like, time-restricted eating is also associated with improved healthspan, the healthy portion of their lives, and longevity, its length.

Other forms of fasting include intermittent fasting, where you alternate between periods of fasting and eating measured in hours or days, and periodic water-only fasting, where you abstain from foods but are not limited for water hydration. While the latter may have some safety concerns, all three restricted eating protocols provide rodent protection from disease and increase lifespan.

While all three fasting schemes make a difference, the researchers sought to test a diet that mimicked a fasting diet (FMD) for us less disciplined humans. [1] This plant-based diet can regulate four specific metabolites to mimic fasting.

- IGF-1 Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 is a peptide hormone produced in response to growth hormone that promotes protein synthesis to increase muscle mass and strength, regulates metabolism, enhances tissue repair and regeneration, and supports cognitive function.

- IGFBP1 Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 1 binds to IGF1, increasing its bioavailability. Its levels increase with fasting. In addition to playing a role in insulin resistance, it may act as both a tumor suppressor and a promoter

- Glucose is an essential molecule for life, serving as a primary energy source for cells and playing a crucial role in various metabolic processes.

- Ketone bodies are organic compounds produced by the liver during periods of low glucose availability. They serve as an alternative fuel source for the body, particularly the brain. They may offer various physiological benefits, including improved energy metabolism, appetite regulation, anti-inflammatory effects, and cellular signaling.

FMD is only a 5-day intervention and has been shown to have “positive effects on both cellular function and healthspan” in rodents, targeting dysfunctional cells and allowing for “regeneration or reprogramming” of more functional cells during refeeding.

Study Question

In their previously published work using a 5-day FMD for three months, the researchers demonstrated reductions in weight, trunk and total body fat, blood pressure, and IGF-1. Using the same FMD cycles, they wondered whether there were, in addition, improved levels of aging, thus reducing one’s biological age. We might say that from a biological perspective, age as a measure of health is a social construct and a poor one at that – we all know both the spry and the frail.

Measuring aging

Not only do humans age differently, but aging within the body is heterogeneous, so time “is not a reliable proxy of the physiological changes that are associated with the biological aging process.” Additionally, our lifespan is far longer than rodents, so human aging studies require biomarkers, surrogate markers for functional changes. In addition to increasing metabolic dysfunction as we age, there are additional changes to our immune system’s composition and response termed immunosenescence, making us more vulnerable to infection.

There are many possible biomarker models. In this research, the model considered the following proxies: Albumin, Alkaline Phosphatase, Serum Creatinine, C-reactive protein, Hemoglobin A1c, Systolic BP, and Total Cholesterol. These are general measures of liver, kidney, and cardiac function, glucose and fat metabolism, and background inflammation.

Using the model, one can calculate biological age and then use representative actuarial tables to predict morbidity and mortality risk. Yes, there is a bit of Mathmagic at play. One more specific assumption by the researchers is of note.

“Furthermore, because the markers which make-up the composite biological age are modifiable, this measure may facilitate evaluation of interventions, such as our FMD trial, aimed at slowing the aging process and delaying disability and disease.”

However, like the concern about tau tangles in Alzheimer’s, it is unclear whether altering the biomarkers will lengthen or diminish one's life.

One hundred study participants were randomly assigned to FDM or their regular diet. After three months, those eating a normal diet were “cross-over” to an FDM diet for an additional three cycles (months) – yielding 71 participants following an FDM protocol for three months.

- FMD reduced both abdominal and hepatic fat. A ratio of hepatic fat to total fat (Hepatic fat fraction, HFF) of >5% indicates steatosis, which, while initially protective, in its more chronic form, is a leading cause of non-alcoholic liver disease promoting liver inflammation. For the few individuals with HFF ratios of >5%, there was a 50% reduction in their HFF.

- FMD reduces insulin resistance and normalized glucose tolerance “in individuals that had fasting glucose levels indicative of pre-diabetes.”

- FMD impacted the participant's immune profile. As we age, we produce fewer lymphocytes, lymphopoiesis, and up-regulate genes increase more myeloid-lineage cells, i.e., Granulocytes, Monocytes, Megakaryocytes, and Dendritic Cells. As a result, our L/M ratio shifts. FMD increased the L/M ratio in the over-40-years-of-age participants “consistent with previous results in mice indicating rejuvenating effects on the immune system.” There was no similar improvement in the control group.

- FMD reduced biological age as measured by their biomarker model. While all the participants were biologically younger than their chronologic age at study entry, the FMD participants were 2.5 years younger after 3 FMD cycles; the controls “exhibited a non-significant average biological age increase of 0.78 year.”

Before beginning your own FMD program, there is at least one caveat. 30% of those participants in the FMD arm increased their biological age. The researchers hasten to point out that this was slightly less than the 63% of the control group who increased their biological age. Further analysis suggested that systolic blood pressure and C-reactive protein levels were “clearly distinct” in separating responders from non-responders. As they go on to point out, both are relatively more labile, responding to acute conditions, so these differences may reflect a “temporary” increase in biological age.

“Weight Loss Alone Does Not Account For The Decrease In Biological Aging.”

Despite the rush for the GLP-1s, the researchers found no association between changes in weight and biological aging. As they write,

“In summary, these simulations suggest that although weight loss may contribute to changes in variables used to estimate biological age markers, weight loss alone does not explain the effects of FMD cycles on biological age and disease risk.”

They found that significant associations of changes in biological age were related to albumin, a measure of liver function, C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation and immune response, systolic blood pressure, a measure of vascular tone and cardiac function, and HbA1c, a marker of energy metabolism – “no single marker alone was responsible for the declines in biological age, but rather this was the result of a system-level improvement.”

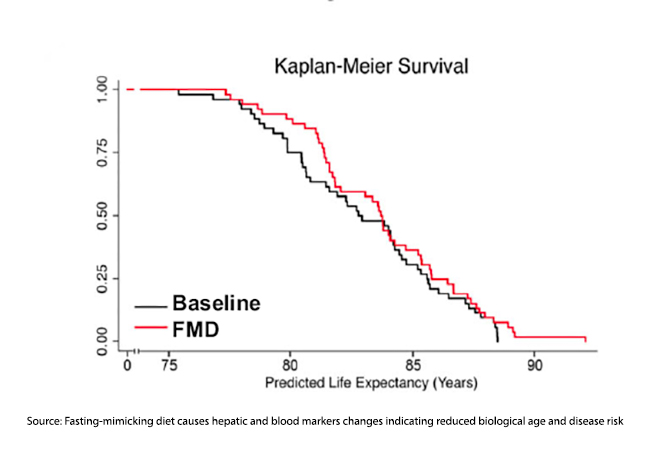

Using the model and the assumption that reductions in biological age increase life expectancy, the researchers calculated that just 3 FMD cycles would add just a few months to your life. And most of those gains were a reduction in early deaths. Moreover, the gains were most significant the earlier they occurred. FMD was a young person’s game. In a modeling where three cycles of FMD were performed annually, there appeared to be a limit to how great a reduction in biological age might be – at best, allowing you to remain in place aging ten months biologically for every 12 months of chronologic time.

Using the model and the assumption that reductions in biological age increase life expectancy, the researchers calculated that just 3 FMD cycles would add just a few months to your life. And most of those gains were a reduction in early deaths. Moreover, the gains were most significant the earlier they occurred. FMD was a young person’s game. In a modeling where three cycles of FMD were performed annually, there appeared to be a limit to how great a reduction in biological age might be – at best, allowing you to remain in place aging ten months biologically for every 12 months of chronologic time.

Finally, the 10.5% relative reduction in mortality risk was not shared equally across diseases. It was biased towards diseases with more robust associations with food, with a 17.4% relative reduction in cardiac mortality, 22% relative reduction in cerebrovascular mortality, 26% relative reduction in deaths associated with diabetes, but only a 6.4% relative reduction in cancer-related deaths.

“Given that the risks for most major chronic diseases rise exponentially with biological age, the slowing of the aging process could lead to a prolonged disease-free life expectancy by delaying the onset of age-related chronic conditions or slowing the accumulation of multi-morbidities.”

Whether this study has found a fasting fountain of youth remains unclear. The study participants were younger than their age at baseline, and only changes to biomarkers and their subsequent effect on models were observed – “these are estimated risk reductions and decreases in mortality were not directly observed in this study.” Their work also assumes “that associations between biological age and mortality also reflect the effect of change in biological age—which has yet to be proven.”

While traditional wisdom has preached nourishment for optimal health, this research suggests that controlled periods of fasting could hold the key to unlocking a longer, healthier life. It's essential to recognize that the findings are not without ambiguity. While the study sheds light on the potential benefits of fasting, it also underscores the need for further research to fully understand its implications.

[1] “The FMD is a plant-based diet designed to attain fasting-like effects on the serum levels of IGF-1, IGFBP-1, glucose, and ketone bodies while providing both macro- and micronutrients to minimize the burden of fasting and adverse effects. Day 1 of the FMD supplies ~4600 kJ (11% protein, 46% fat, and 43% carbohydrate), whereas days 2 to 5 provide ~3000 kJ (9% protein, 44% fat, and 47% carbohydrate) per day.” Foods include “vegetable-based soups, energy bars, energy drinks, chip snacks, tea, and a supplement providing high levels of minerals, vitamins, and essential fatty acids.”

Source: Fasting-mimicking diet causes hepatic and blood markers changes indicating reduced biological age and disease risk Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-45260-9