“Twelve percent of the global human population is undernourished, and acute protein deficiency in low-income countries is compromising workforce productivity and development.”

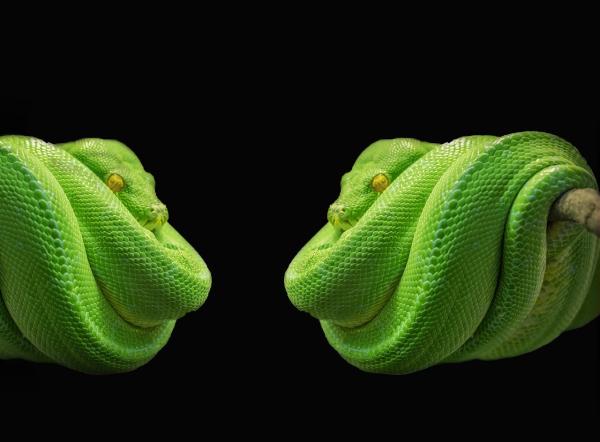

And with that opening, a new study in Nature reports on farming what might become “the other white meat,” snakes. Being ectotherms (cold-blooded), they provide natural savings compared to their endothermic competitors, and while they may not be on the plate for Western cultures, snakes and insects have a place in other cultural diets. To examine the potential of snake herding, the researchers examined “the growth patterns of two python species in two commercial farms in Southeast Asia” – one in Thailand and the other in Vietnam. The Burmese and reticulated pythons can quickly grow to more than 100 kg, and the females are particularly fertile, producing up to 100 eggs annually. Besides the occasional rodent, the pythons were fed waste proteins from chicken, pork, and fish food chains and housed in warehouses.

Pythons were measured [1] and weighed at birth and six and twelve months of age, having been fed essentially weekly over the interval. A subset of pythons was given a variety of diets, including:

- 100% pork

- 90% pork and 10% chicken pellets

- 90% pork and 10% fish pellets

- 80% pork and 20% fish pellets

- 100% wild-caught rodents – Is this the free-range option?

Pythons grew quickly, up to 20 grams daily, and the dietary choices made no significant difference in final growth. About two-thirds of the Pythons fasted for periods greater than two weeks. They lost little body mass during this period and resumed growth when they began to eat again. For every 4gms of feed, pythons produced 1 gm of meat – a feed conversion ratio (FCR) of 4.1:1. For comparison, chickens FCR is about 2, pigs 4.0 and beef 6-10

“Our studies confirm earlier work, that it is biologically and economically feasible to breed and raise pythons in captive production facilities for commercial trade.”

Growth rates were flexible and driven primarily by food intake. Pythons are very efficient in extracting energy and building materials from their food. The absence of lost body mass during fasting appears to result from the rapid downregulation of their metabolism after a meal that mimics their natural feeding pattern. This ability to fast and not lose weight makes them a resilient food stock.

They have an FCR and protein conversion rate compatible with another ectothermic food source, salmon. And yes, they produce fewer greenhouse gases – primarily, their high-efficiency assimilation of food “translate[s] into low volumes of feces.”

The last word to the researchers.

“In countries with a cultural precedent for eating reptiles, and where food security is increasingly compromised through the impacts of global challenges such as climate change, reptiles offer an efficient, safe, and flexible source of protein.”

In a world where food security is a pressing concern, and the specter of protein deficiency looms, it's time to think outside the barnyard. Snake herding offers a tantalizingly efficient, safe, and flexible solution. With their rapid growth rates, minimal environmental footprint, and impressive protein conversion ratios, pythons may be a future of farming.

[1] Much like we might refer to nose-to-tail measurements, for the snake, we measure snout to vent. The vent is the junction of the body with the cloaca, an organ combining the waste vents for urine and feces.

Python farming as a flexible and efficient form of agricultural food security Nature Scientific Reports DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-54874-4