Born in 1842 and home-schooled, but driven by a fierce love of science and nature and not one to be easily deterred, Ellen Henrietta Swallow was the first woman to attend and graduate from MIT ( then called the Institute for Technology) earning a Bachelor’s degree in chemistry. Simultaneously, she earned a Master’s in Chemistry from Vassar – soon becoming America’s first professional woman chemist. Two years later, she married Professor Robert Hallowell Richards, MIT's head of mining engineering. As his life became hers, she became both collaborator and independent researcher, becoming the first woman elected to the American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers in 1879.

A year after she married, she became an instructor in the Women’s Laboratory connected with MIT, sometimes called “Mrs. Richard’s Laboratory for women, which she was instrumental in founding, directing, teaching, advising, and fund-raising. For the next seven years, she worked without pay, mothering and mentoring the girls who came to study and contributing from her own pocket in support. Graduates from her laboratory went on to teach at Wellesley, Smith, and Pennsylvania College, among other educational institutions.

By 1883, she had integrated scientific study into domestic activities, measuring ventilation (recognizing, even then, the dangers of “tight building syndrome,” which occurs when a building lacks sufficient ventilation), evaluating heating and gas exposure in the home, and analyzing the nutritional value of foods as part of a small “Sanitary Science Club” membered by women of like intellectual disposition. In this capacity, she wrote The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning, and Food Materials and Their Adulterations, updating an 1879 lecture given by astronomer and her Vassar Professor, Maria Mitchell, on “Chemistry in Relation to Household Economy.”

Her focus on domestic science was soon dwarfed by the pursuit of more chemically related endeavors. In 1884, she became an instructor in Sanitary Chemistry at MIT, authoring a text called “Air, Water, and Food,” which described chemical analysis of each, providing the blueprint for her life as a public health officer, then called “sanitarian,” as a practitioner, program developer, and educator of hundreds of students who carried her message to classrooms and public health offices throughout the country.

In 1884, MIT opened the first laboratory in the world for sanitary chemistry, and Ellen became its chief assistant until the unit was transferred to the State House in 1897. Her work depended on consistent and regular sampling and meticulous accuracy, for which she was renowned. She also introduced biology into the MIT curriculum and helped to establish the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. That same year, she was appointed chemist for the Manufacturer’s Mutual Fire Insurance Company to investigate the dangers of spontaneous combustion of oils in commercial use. In this role, she developed new methods for determining impurities in lubricating oils; in 1877, she devised a new quantitative assay for nickel in ores, becoming an authority on the subject and frequently mediating commercial disputes.

Her focus on testing water quality ( becoming an expert on water and sewage analysis) made her an invaluable asset to the newly formed Massachusetts State Board of Health. In 1887, she began an extensive sanitary survey of the state water supply, and her analyses became the foundation for the National (Normal) Chlorine Map, a standard for sanitary surveys. The map identifies the natural levels of chlorine in unpolluted waters, mapping and establishing normal chlorine baselines, which can determine if a sample comes from polluted waters or waters naturally chlorinated.

In 1890, MIT inaugurated the first systemic course in Sanitary Engineering, in which Ellen prominently taught sanitary water, sewage, and air/ventilation analysis. She is credited with not only educating her students but also inspiring them in social and community service (then called “the desire to serve one’s fellowmen”). It was said of her that “she sent from her laboratory and classroom ‘missionaries to a suffering humanity.’

While paid for some work, she also furnished services gratis for causes close to her heart, including testing Vasser’s water supply to determine the efficiency of a recently installed sewage disposal plant.

“[H]ome meaning the place for the shelter and nurture of children or for the development of self-sacrificing qualities and of strength to meet the world; economics meaning the management of this home on economic lines as to time and energy as well as to money.”

- Ellen Swallow Richards

Her subsequent pursuit involved developing public kitchens where cost-effective and nutritionally sound foods could be procured. Here, she delved into the economics and science of nutrition. Her interest in nutritional management was holistic, weighing the human energy and costs involved in producing, transporting, preparing, and serving food and bemoaning the great toll food “should take in sickness, waste, and inefficiencies.”

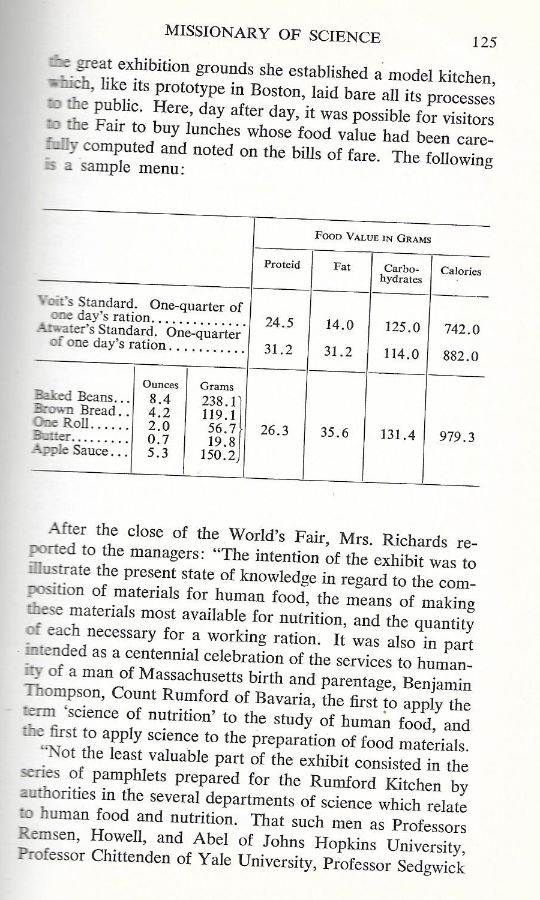

With Dr. Thomas Drown, professor of Chemistry at MIT, and colleague Mary Hinman Abel, they selected various foods [1], identifying their nutritional content by weight and nutritional content, calculating the amount of fat, carbohydrates, and “proteid” along with preparation costs. This endeavor launched for Boston’s Public School Lunch Program. Her report of nutritional chemical analyses was presented to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in 1890 and published in 1899 as the “Rumford Kitchen Leaflets.” along with preparing technical bulletins for the USDA

Her clear nutritional tables, presented at the World’s Fair of 1893, where she established a model kitchen, were depicted in a 1912 biography by an acolyte, Caroline L. Hunt, which reads more like a testimonial to an icon- a dense litany of accomplishments in a short lifetime – than a traditional story of someone’s life.

“The Life of Ellen H. Richards,” Caroline L Hunt, American Home Economics Association, 1958, Page 125, Table on Food Value in Grams.

Indeed, Ms. Hunt recounts how Mrs. Richards maximized every minute of every day, incorporating a “mindfulness,” advocating (and partaking in) exercise as a needed adjuvant to healthy living and thinking, noting her careful appreciation of the landscapes in which she walked or collected specimens. She also details Ellen Richards’ gift of leadership, empowering women to support other women and organizing and inspiring an association of alumni of women’s colleges, which became the forerunner of today’s American Association of University Women.

Her scientific studies of home management coalesced at the “Lake Placid Conferences,” convened in 1899, and where the term “Home Economics” (now often referred to as “Human Ecology”) was first conceived and used. The intellectual rigor of her approach was apparent in a dispute with a colleague, Melvil Dewey (of the Dewey Decimal System), who wanted to classify the subject as a “production art.” Eager for the subject to develop “along the right lines,” she objected, advocating for its classification under “the economics of consumption.” But Mrs. Richard’s vision and mission were clear and prescient and as true today as when she wrote in 1898:

“Ten years ago domestic science meant to most people lessons in cooking and sewing given to classes of the poorer children… to enable them to teach their parents to make a few pennies go as far as a dollar spent in the shops….So, also, the tradition of valuelessness of a woman’s time kept the plain sewing to the front, and classes were taught [in] seams and ruffles, and cheap ornamentation….As late as… 1903, the work of public schools of this country was … bad from an ethical point of view, showing waste of time and material…. The work of the American public schools must have an ethical quality if it is to give us good citizens….”

The discussions held at the Lake Placid Conference led to her proposal of a course of study in “home economics” involving nutritional investigation and analyses, including “The Cost of Living,” “The Cost of Food,” and “The Cost of Shelter,” subjects which today’s self-respecting economist would jealously guard under their purview, wrinkling their noses at the association of these matters with the pink-collar world of home economics.

She died in 1911 at the age of 68. If she accomplished so much, it can only be because she maximized every moment of her day, not just in doing or performing acts of kindness but in appreciating the beauty of nature around her.

[1] “Beef broth, vegetable soup, pea soup, corn meal mush, boiled hominy, oatmeal mush, pressed beef, beef stew, fish chowder, tomato soup, Indian pudding, rice pudding, and oatmeal cakes,… food intended to supplement those prepared in the homes of the people.”

Source: The Life of Ellen H. Richards Caroline H. Hunt, 1912