PFAS, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are thousands of chemicals used in consumer products dating back to the 1940s. The two most prevalent and studied PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS, were voluntarily phased out by chemical manufacturers between 2000 and 2015. However, because they stay in the environment for a long time, they are still found in low levels in drinking water, soil, and fish.

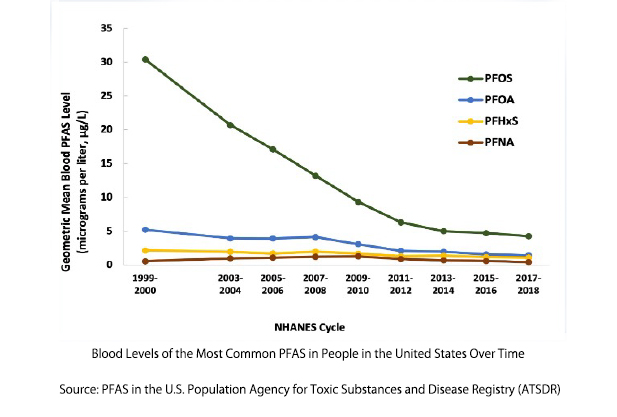

It is not surprising that PFAS has been detected in people’s blood because, over the years, scientists have been able to measure chemicals at lower and lower levels. However, PFAS levels in the blood of the U.S. population have been dramatically reduced over the years. Human blood levels in 2018 were 70% to 90% lower than in 1999 and continue to decline today.

The EPA has continued a relentless focus on PFAS in all venues, the latest being fish. The issue is not whether fish should be added to the monitoring list but whether it is backed by science.

Who Regulates PFAS in Fish?

Most fish are NOT regulated by the EPA and will not be impacted by adding PFAS to the recommended list.

The FDA has the authority to regulate contaminants in food, including fish, sold in grocery stores and supermarkets across the U.S. The FDA has been testing food for five or more PFAS since 2019 in the Total Diet Study and has concluded that

“There is no indication that the five PFAS at the levels found in the limited sampling of foods collected for the Total Diet Study present a human health concern.”

However, if you throw a line into your local river or stream and catch lots of fish, these additions could impact you.

States may issue fish consumption advisories for contaminants in recreational, not commercially sold fish they have determined present a risk to human health. These advisories layout “do not eat thresholds” for levels of contaminants found in fish.

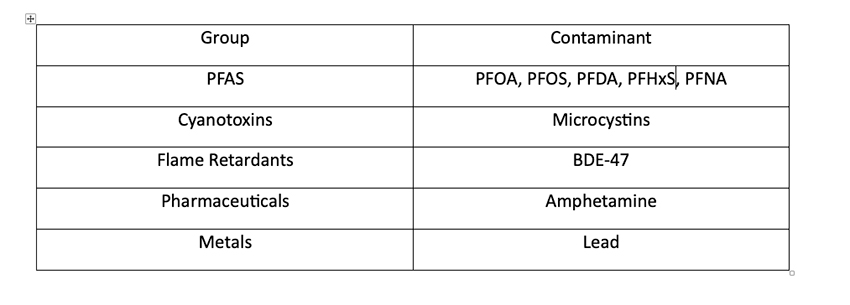

Although States issue fish consumption advisories, the EPA has issued recommendations for states as to which contaminants they recommend they analyze for in fish tissue and issue fish consumption advisories. The following table shows the contaminants that EPA recently added to the list.

In issuing a news release, the EPA noted that PFAS was added to the list because their “most recent National Aquatic Resource Survey, which monitors fish tissue from lakes and streams across the country, and numerous other studies have found PFAS in freshwater fish and shellfish at levels that may impact human health.”

What Would a Science-Based Process Look Like?

A science-based process would model the results of statistically based surveys across the waters of the U.S. to examine the levels of PFAS in fish and correlate these with past contamination. A model could help determine where the PFAS levels are high in fish, and it is recommended that states monitor these areas for contaminated fish. It would compare these levels with independently developed health values accepted globally and issue advisories only for areas at risk.

What was the EPA’s process?

EPA searched the literature for published articles that identified the concentrations of chemical contaminants found in fish in the U.S.

EPA used equations from a 24-year-old document, Guidance for Assessing Chemical Contaminant Data for Use in Fish Advisories: Volume 1 (epa.gov) [1] to determine if the levels found in fish in the literature would exceed thresholds for an adult in the general population, a pregnant woman, or a frequent fish consumer. Adults in the general population were assumed to eat 8 ounces per week of fish, and frequent fish consumers were assumed to eat 5 ounces daily. These levels were then compared to “safe levels” of the contaminants determined by EPA, such as health advisories. If any exceeded one or more of them, the contaminant was placed on the “should be monitored” list.

Issues with EPA’s Approach

The biggest problem was that the EPA was not transparent. They did not release the citations or concentrations of the contaminants in the articles, making it impossible to check their work and determine if actual data backed up their conclusions.

As discussed in a previous ACSH article, PFAS is removed through washing and cooking, a significant fact that was not considered in the equations used to determine if the contaminant should be monitored. How fish is prepared does make a difference, with one study showing that washing removed 74% of PFOS, with grilling removing 91%, steaming 75%, frying 58%, and braising 47% compared to uncooked samples.

In addition, EPA used “safe levels” for PFAS that are well below levels that could harm human health. These levels are so low that almost any levels detected in fish tissue will exceed them. Also, the chemical concentrations pulled from published articles are not representative of levels found across the U.S. These articles are usually conducted in areas of heavy contamination, where PFAS is most likely to be seen.

The EPA’s claim that the most recent National Aquatic Resource Survey showed that PFAS has been found at levels that impact human health is incorrect. The National Aquatic Resource Survey is not a single survey, but several surveys were done collaboratively between the EPA and the states. Out of four surveys, the only survey that tested for PFAS was the National Rivers and Streams Assessment, which reported that most (91%) of the 290 fish fillet samples tested in 2018 and 2019 had PFOS levels above the method detection limit of 0.35 parts per billion (ppb). However, there is no indication that these levels threaten human health.

There is no excuse for the EPA to release a news release adding PFAS to the recommended fish consumption advisory list without providing the documentation for the results. Clearly, with the EPA's focus on PFAS, it is imperative that the Agency use a science-based approach and be transparent about its work.

Most people (over 90%) in this country consume commercial fish, not fish caught recreationally. Even for those people who fish recreationally, roughly 60% is not consumed, but is “catch and release.” The bottom line is that virtually everyone is OK to eat fish on Friday.

[1] In an ironic twist, as a young toxicologist in the 1990s, I worked on this document for several years under contract to the EPA. Although the EPA says they are updating the document, I was surprised that this is still the official EPA documentation for the fish advisories.