The notion of human medical experimentation elicits visceral repulsion. Nevertheless, we allow such research for the betterment of society, but only with safeguards to protect the volunteers. These guardrails include an evaluation by an impartial ethics board that weighs the risks and benefits and full informed consent by the participants, governed by policy rubrics, applicable statutes, or international guidelines. Sometimes, however, there is research overreach, commingled with shoddy and/or obfuscatory study reporting. Only if something untoward happens does the public (sometimes) find out. So, volunteer, be warned.

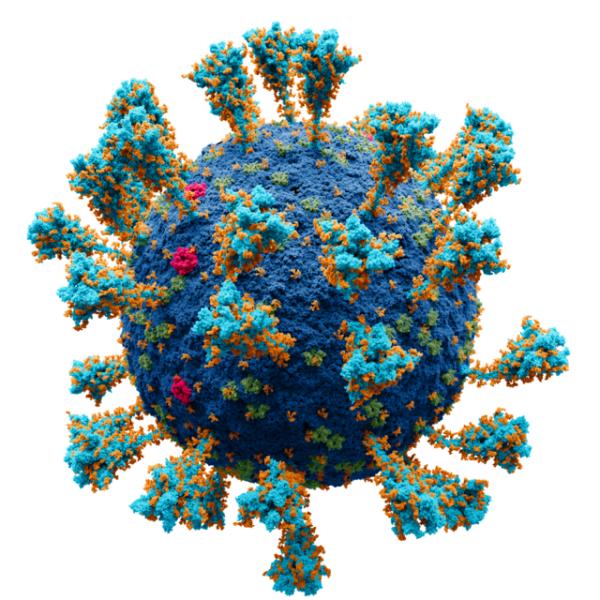

With these caveats in mind, we were surprised and puzzled by a recent study published in eClinical Medicine (a Lancet publication). It evaluated cognitive impairment following infection by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the etiologic agent of COVID-19. This was not a clinical trial designed to test the safety and efficacy of a new treatment, drug, or vaccine. Nor was it an observational cohort of past illness, nor a prospective study that monitored population segments over time.

Rather, the study involved what is called a virus “challenge”: 34 healthy, unvaccinated volunteers between the ages of 18 and 30 were studied, cognitively tested to provide baseline levels of 11 cognitive tasks, and then inoculated with the SARS-CoV-2 virus to determine whether they would contract COVID and if so, whether it would affect their cognitive abilities. Six volunteers “pre-emptively” received the anti-viral drug remdesivir (100mg IV for 5 days) “to mitigate risks of severe illness” (No information is given on how these six were chosen).

Ultimately, 18 participants were classified as infected, 16 were not, and it is unclear in which group(s) the remdesivir-pretreated subjects were found. While no serious adverse outcomes were reported, moderate reactions did occur, but, again, it is unclear whether those occurred in the remdesivir or untreated group.

The article claims that the screening protocol and study were subjected to critical review, approved by the UK Health Research Authority, and conducted in accordance with international ethical guidelines, including the Helsinki Declaration, the guiding bioethics document for European Research activities. But it strikes us that some not-so-funny funny business is going on here, all protestations of ethics compliance notwithstanding.

The researchers claim that the “information [submitted] … is consistent with current knowledge of the risks and benefits of the study intervention and with the moral, ethical and scientific principles governing clinical research as set out in the current Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Good Clinical Practice (GCP).”

Let’s take a deeper look….

In 1964, and in the shadows of Nazi experimentation of WWII, the World Medical Association (WMA) convened in Helsinki to draft “a statement of ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects…” The Declaration binds the researcher/physician to the standards that, “The health of my patient will be my first consideration,” and that, “A physician shall act in the patient’s best interest when providing medical care.” This duty “includes those who are involved in medical research.”

While acknowledging that the primary purpose of medical research is to generate new knowledge, the Helsinki guidelines assert that “this goal can never take precedence over the rights and interests of individual research subjects.”

Risks, Burdens, and Benefits

The Helsinki Declaration further imposes on the reviewing ethics committees the duty to evaluate risks vs. benefits:

Medical research involving human subjects may only be conducted if the importance of the objective outweighs the risks and burdens to the research subjects… Physicians may not be involved in a research study involving human subjects unless they are confident that the risks have been adequately assessed and can be satisfactorily managed.

(In the US, The Common Rule provides the policy governing all human subject research “subject to regulation” by a federal department or agency, and the GCP (Good Clinical Practice) provides explicit guidelines.)

As to whether these objectives were achieved here, several interesting points emerge:

- First, this is portrayed as a separate, stand-alone study. It isn’t. The study was done in two parts; the first reported in Nature Medicine: “[The] study's primary objective was to identify an inoculum dose that induced well-tolerated infection in more than 50% of participants, with secondary objectives to assess virus and symptom kinetics during infection.” (What constitutes a “well-tolerated” infection is undefined.)

- Under any ethical inquiry, the risk-benefit ratio must calculate the likelihood of achieving reliable answers to the stated hypotheses, which is given in the primary study as examining whether:

- SARS-CoV-2 infection in experimentally infected healthy young adult volunteers is safe and well tolerated, [and whether] Experimental COVID-19 allows early viral replication to be measured and enables monitoring of innate and adaptive immune responses and radiological changes which act as surrogates of protection and disease.

According to the protocol, the study would comprehensively describe the infection rate, host immune responses, viral kinetics, and clinical disease induced by pre-emptively treating infection. Also contained in that protocol are what the investigators considered to be the foundation for the study discussed here, which was intended to examine the impact of COVID infection on cognition.

But are these rationales sufficient to justify the risks of a SARS-CoV-2/COVID challenge? Would a reasonable person consent to such experimentation – that is, without the compensation offered? Compensation is, indeed, an accepted element of any human research, but in the US, at least, care must be taken that the compensation is not unduly excessive, inducing volunteers to disregard the risks.

In this study, the volunteers received about $6000 for their “time,” which included 17 days of quarantine and five follow-up visits for cognitive testing over the ensuing year. The researchers claim this figure was calculated using the UK national living wage index and an NIH Research formula. However, we wonder: The median annual UK salary for 18-22-year-olds during 2020-21 was $21,000, and for 22-29-year-olds, it was $35,000.

The manner in which the risks and benefits were disclosed to prospective participants in the experiment is rather unsettling. Per the study protocol:

Young healthy adults in the 18-30 year old age are at low risk of severe outcomes following COVID-19. As of 6th November 2020 in England and Wales, 95 individuals in this age range have died due to COVID-19, but most had risk factors. Risk of hospitalisation in this age group (without accounting for comorbidities) has recently been estimated at 0.08-0.39%. Protracted symptoms (‘long COVID’) can occur but are less common in young people with mild disease...

But those statistics were early in the pandemic, and by the time the study was completed (uninterrupted) in July 2022, the mortality rate of young people had mushroomed. There is no indication the volunteers were informed about new data. Indeed, by February 2022, about 2500 deaths had been reported in this age group in the UK.

How about the experiment's benefits, the other part of the equation? The volunteers were told: “Healthy participants in clinical studies will not receive direct benefit from treatment during their participation...[but] participants are contributing to the process of developing new therapies in an area of unmet medical need.” The nature of such new therapies was not specified, nor do any new therapy candidates seem to have arisen from the study.

Not surprisingly, cognitive declines were detected compared to baseline measurements taken before the study began. But the study design did not allow for the determination of cause and effect—the effects could well have been due to the stress and disorder of the times, i.e., living through a pandemic: No dose-response calibration was performed either of viral load or disease severity, nor were statistical parameters followed to provide statistical significance of these results. Nor did the cognitive deficit study result in new interventions. Indeed, seemingly, none were tested.

Moreover, given that no official “control” group was part of the study, it is impossible to rule out other confounding variables.

Finally, the participants did not note any subjective cognitive limitations were noted by the participants, meaning that they weren’t even aware they were cognitively challenged, making it difficult to determine whether therapeutic interventions would be indicated or applied. (In other words, if an individual isn’t aware of a cognitive problem, it is likely that they would not seek treatment or medical intervention, even if one were available.)

Did the Study Fulfill Its Stated Purpose?

Although the stated objective of this leg of the study was to assess COVID-related cognitive decline, the study protocol stresses only that the study’s purpose was to assess the development of vaccines and improve their efficacy – primarily in the elderly. And while the participants were given an overall risk-benefit assessment, it had nothing to do with cognition. Indeed, the claimed benefits seem dubious, at best:

Overall benefit: risk conclusion… the potential risks [to the individual, including death] are justified by the anticipated benefits linked to the evaluation of a viral challenge model … developed to … [generate] an efficient method of testing vaccine efficacy. Furthermore, the viral challenge model will also subsequently contribute to the identification of mechanisms of protection against viral infection and shedding.

There are other problems with the study. As to the lack of generalizability of results from young to older people, here’s this gobbledygook provided in the protocol:

How is this research relevant to patients? While young healthy adults may not fully recapitulate high risk groups, they provide a benchmark for optimal protective immunity and are highly suitable for antiviral and monoclonal antibody testing. People in this age group...will be the main target for vaccines that aim to prevent asymptomatic transmission by reduction of viral shedding in the upper respiratory tract.

By the time the main study proposal, dated February 21, 2021, was submitted (the study began two weeks later), Pfizer’s vaccine had been available for three months. Thus, the stated rationale for the study seems shaky. Indeed, the authors themselves admit that, “This was the first, and likely will be the only Human Challenge study in which unvaccinated virus naive volunteers were inoculated with Wildtype SARS-CoV-2…” [Emphasis added] They conclude that the clinical implications of the cognitive changes observed in some of the infected subjects “remain unclear.”

Conflict of Interest

In assessing study propriety, ethics committee members must consider researchers’ conflicts of interest. Interestingly, three of the named authors of this cognitive challenge study (the first, second, and last) have a proprietary interest in a company called “H2 Cognitive Designs,” which “designs” and “markets” cognitive testing platforms for healthcare and research.”

Seems to us that this study will not win any prizes for excellence in clinical research or adherence to ethical standards.

Barbara Pfeffer Billauer, JD MA (Occ. Health) Ph.D., is a Professor of Law and Bioethics in the International Program in Bioethics of the University of Porto and a Research Professor of Scientific Statecraft at the Institute of World Politics in Washington DC.

Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is the Glenn Swogger Distinguished Fellow at the American Council on Science and Health. He was the founding director of the FDA's Office of Biotechnology.