Roughly 20% of medical schools have accelerated learning programs designed to graduate physicians in 3 rather than 4 years. An early iteration of accelerated learning was based on a concern over physician shortages – but at best, accelerated learning would add only one additional year of graduates, roughly 28,000, to eliminate an estimated shortage of 64,000. The goal of today’s accelerated programs is to decrease student debt along with additional “missions” to

“Expand workforce in primary care and underserved areas and [recognition] that medical education can be individualized for specific students.”

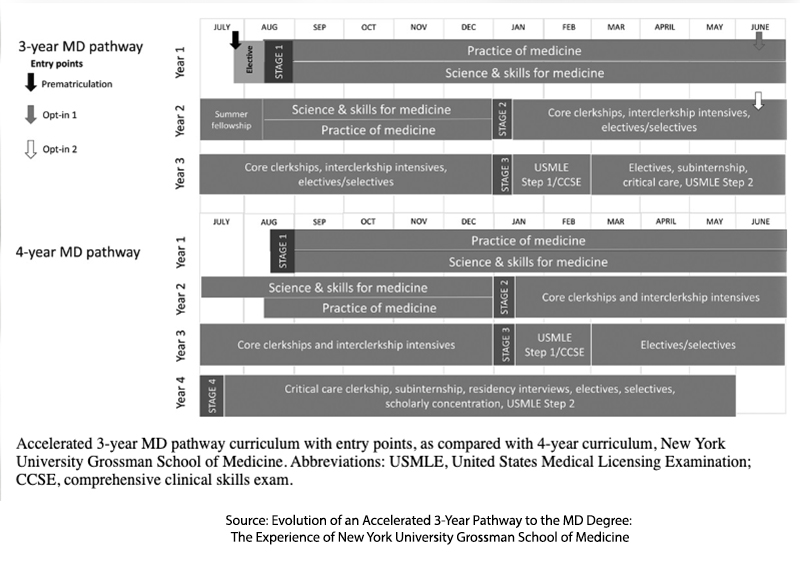

The counterbalance to the push to accelerate graduation has been a concern that physician competency is being sacrificed. A new study from NYU’s Grossman School of Medicine addresses that concern. Their 3-year program with identical academic requirements reduced time to graduation by an entire year, actually by 12%, given that a 4-year graduate attends courses for 148 weeks (2.8 full years). These 3-year “pathways” come with conditional acceptance into NYU’s post-graduate residency training and can be entered upon admission or at the end of the first or second academic year. The differences in the 3- and 4-year programs revolve around the additional electives the four-year students undertake.

During the 7-year interval assessed (2016-2023), about 20% of the graduating students took the 3-year path. Approximately 15% entered primary care pathways (which included Obstetrics-Gynecology and Pediatrics). Adding in those entering Internal Medicine, which more frequently serves as a gateway to medical specialties, the percentage entering primary care would rise to 41%. Clearly, accelerated learning does not explicitly meet our challenges in providing primary care physicians.

Concerning expenses, NYU Grossman Medical School, like its older sibling NYU Langone Medical School, is tuition-free, so that additional year of school costs medical students an extra $30,000 in living expenses or a reduction of slightly less than 30% for a 3-year student. Data on where graduates practice is a bit less clear, partly because there is a 3–4-year lag between graduation and entering practice. But if the 3-year graduates are impacting NYU Grossman’s contribution to underserved areas, that impact is low as US News and World Report ranks NYU Grossman at #109 (they rank the school #165 in those graduating in primary care).

With respect to competency, 3-year graduates were equivalent in their test scores [1] across a range of academic and clinical measures except for:

- US Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) Step 1 and Step 2 – this examination is a requirement for medical licensure across the US. Step 1 evaluates basic science, and Step 2 basic clinical knowledge. Step 3, completed during residency, evaluates patient management. Students are estimated to spend roughly 200 hours preparing for each of the first two steps of the 8-hour examinations.

- Physical examination portion of the Comprehensive Clinical Science Subject Exam (CCSSE).

To be fair, the difference, while statistically significant, differed by a tiny percentage of points. It would be safe to say that their basic knowledge was equivalent. Whether they will make as good or better physicians if you are numerically oriented, must wait for the results of their Step 3 tests, but I would suggest that this is only one of many factors that result in a “good” physician.

I did find the reasoning for the discrepancy, as voiced by the authors, insightful. They posited that the 3-year students did not have sufficient time to prepare compared to their 4-year colleagues. However, both groups took Step 1 at the same time, and it was on this portion that the greatest statistical disparity in scores was identified. Alternatively, they suggested that 4-year graduates needing higher scores for their residency application were more motivated to study and score higher.

The researchers make a good case for reducing the time spent in medical school. The fears surrounding diminished competence, as measured by book learning and tests, appear not well-founded. However, their initial data does not support the idea that less time in school motivates individuals to enter primary care or work in underserved areas. Time in school can be reduced by simply ending “summer vacation.” After all, these young adults will soon be entering a healthcare workforce where they will be given vacation in one- or two-week blocks. This data cannot be used to determine the impact of debt reduction, as NYU schools are both tuition-free.

NYU Grossman’s three-year grads are scoring just fine, even if their Step 1 and Step 2 scores are slightly lower than their four-year peers. And maybe they’re not flocking to underserved areas; however, they save on an extra year of rent in New York City, which is a victory in itself. As for fixing the physician shortage? Fast-tracking doctors seem more like a Band-Aid than a solution.

[1] NBME shelf exams, Peer assessments, Patient Care and Procedure Logs, CCSE history taking and communication, Clerkship grades and assessments, Rates of induction into AOA (Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society)

Source: Learning and performance outcomes in medical school and early residency of Accelerated 3-year MD graduates at NYU Grossman School of Medicine Academic Medicine DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005896