Every day, we make choices, often tradeoffs involving numbers, scores, or ratings. Countless websites ask us to quantify our experiences by using likes and stars. Numbers, because they may easily be added, subtracted, multiplied, or divided, are ideal for comparison as we focus on similarities and differences. And numbers seem so definitive, not squishy, like a narrative. A study considers whether numbers exert an undue influence when put against attributes that are not quantified.

“When it comes to making choices—…quantification can create a psychological advantage.”

To get an answer, the researchers conducted a series of experiments in which participants faced choices with tradeoffs; such as price versus quality, and had to select their preferred option. They randomly varied which attribute was shown numerically versus qualitatively while ensuring that the core information stayed constant regardless of how it was presented. The hypothesis is “that decision-makers facing tradeoffs favor options that dominate on the numeric dimension,” termed quantification fixation. Moreover, a facility with numbers, a comparison fluency, helps to drive quantification fixation. Here is what they found:

Does Quantification Fixation Exist?

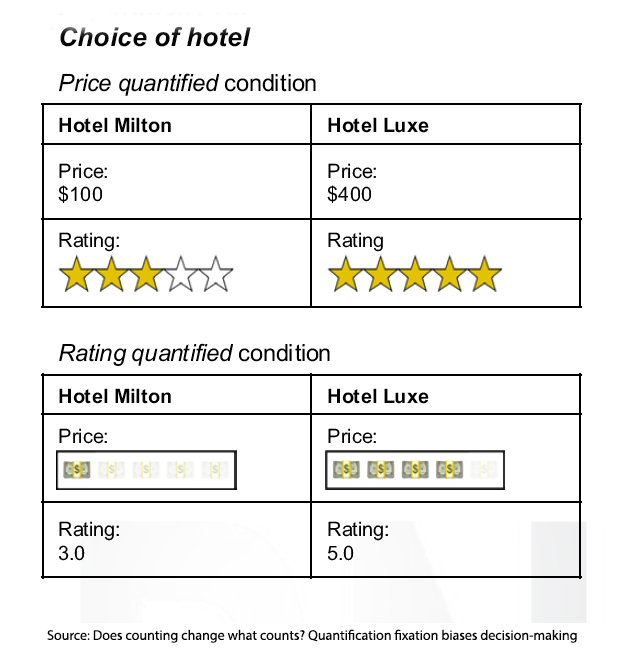

Yes. One thousand online participants chose between two hotels with tradeoffs between price and rating, with either price or  rating presented numerically (the other pictorially with symbols). Participants were more likely to pick the higher-rated, pricier hotel when the rating was shown numerically (51.6%) than when the price was quantified (33.0%). The quantification fixation or dominance of the number over the symbol was confirmed when evaluating a single hotel. For restaurant choices, participants favored the cheaper, longer commute option when price was quantified rather than distance.

rating presented numerically (the other pictorially with symbols). Participants were more likely to pick the higher-rated, pricier hotel when the rating was shown numerically (51.6%) than when the price was quantified (33.0%). The quantification fixation or dominance of the number over the symbol was confirmed when evaluating a single hotel. For restaurant choices, participants favored the cheaper, longer commute option when price was quantified rather than distance.

Does Quantification Fixation Persist with Familiar Descriptors?

Yes. One thousand online participants chose between two candidates for a summer internship, based on grades in calculus and business courses presented either numerically (e.g., 93-97%) or as letter grades (e.g., "A"). 83.8% chose the candidate with the higher management grade when it was quantified, compared to 68.9% when calculus was quantified. Moreover, this effect was held for imprecise numeric ranges, suggesting fixation was not due to numeric precision.

Does Quantification Fixation Persist when Verbal Descriptions (Qualitative) Are Mapped onto Numeric Values (Quantitative)?

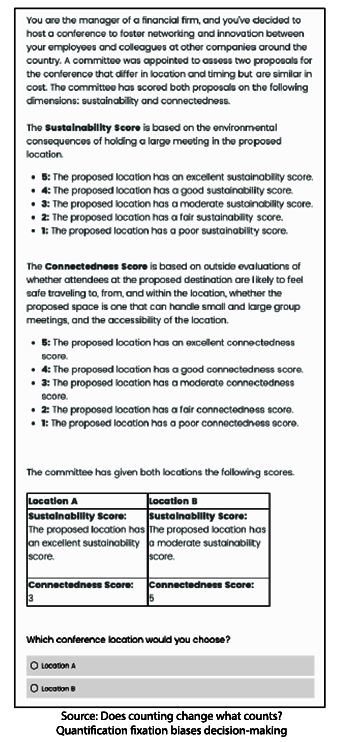

Yes. The image to the left shows the question and how qualitative descriptions are clearly mapped to numeric values. One thousand online participants, acting as financial managers, chose between two conference locations with similar costs and scored on connectedness and sustainability. Participants were randomly assigned to either a condition where connectedness or sustainability was quantified. Despite the explicit qualitative-quantitative mappings, quantification fixation persisted: 78.0% chose the location with a higher connectedness score when connectedness was quantified, compared to 60.8% when sustainability was quantified, confirming the fixation effect.

Yes. The image to the left shows the question and how qualitative descriptions are clearly mapped to numeric values. One thousand online participants, acting as financial managers, chose between two conference locations with similar costs and scored on connectedness and sustainability. Participants were randomly assigned to either a condition where connectedness or sustainability was quantified. Despite the explicit qualitative-quantitative mappings, quantification fixation persisted: 78.0% chose the location with a higher connectedness score when connectedness was quantified, compared to 60.8% when sustainability was quantified, confirming the fixation effect.

Does Quantification Fixation Distort Preferences?

Yes Two thousand online participants, acting as managers, chose between two employees based on advancement potential and loyalty, presented as numbers, words, or a mix. When both attributes were in the same format (numeric or verbal), choices were consistent (27.9% and 32.7%, respectively). However, quantifying only one attribute distorted preferences: participants favored the higher advancement employee when only advancement was quantified (44.2%) and were less likely to choose them when only loyalty was quantified (21.8%). This demonstrates that preferences shift when just one attribute is presented numerically.

Does Quantification Fixation Persist with Incentives?

Yes One thousand online participants selected a candidate to "hire" from other real online workers, earning a bonus based on the candidate’s performance in a trivia game. Each candidate had a higher Math or Angles trivia score, with only one score presented numerically. Even though Math trivia scores better predicted a 6% bonus performance, participants preferred the candidate with the higher Math score in the math-quantified condition (66.5%) over the angles-quantified condition (54.5%).

Does Quantification Fixation Persist in Real, In-Person Decisions?

Yes, Seven hundred participants chose between two charities to receive a $1 donation. Charity Navigator rated each charity on Accountability & Finance and Culture & Community, with one score presented numerically and the other as a bar graph. Participants showed quantification fixation, favoring the charity with a higher Accountability & Finance score (56.7%) when this score was quantified versus only 41.4% when Culture & Community was quantified.

Of course, all of those yeses come with an important caveat: our numerical literacy, termed numeracy, is crucial in all of these scenarios. The researchers describe comparison fluency as the participants' ability to manipulate more complex numbers, e.g., comparison of scores like 75 out of 100 are more easily considered than 51 out of 68. As they noted in another experiment involving two thousand online participants, quantitative fixation weakened when the numeric information was presented less fluently and when participants had lower numeracy – a poorer facility with numbers. People are less likely to overweight numeric information that is more difficult to readily apply to comparisons, and when their numeracy made them less comfortable and able to carry out those comparisons.

“We find robust evidence of quantification fixation: When faced with decisions that involve tradeoffs across qualitative and quantitative attributes, people privilege the quantitative. … quantification fixation is driven by people’s comparison fluency with numeric tradeoffs.”

While this may seem a problem of greater concern to regulators, as a clinician, I can report that it is an everyday concern when expressing risks and benefits to patients. 25% of Americans cannot work with whole numbers and percentages. Given that percentage and an equally concerning percentage of the population that can only read at the 8th-grade level, one can seriously ask whether many of us cannot give fully informed consent when the information is presented in some document created by “legal.”

The research raises pressing questions: if quantifying choices changes our decisions, are we making the best ones? With one in four Americans struggling to grasp basic numbers, let alone tradeoffs, numbers make choices easier but potentially misleading.

Source: Does counting change what counts? Quantification fixation biases decision-making PNAS DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2400215121