In early 2023, as news of H5N1 avian influenza ("bird flu") spreading among dairy cows reached the White House, the stage was set for a high-stakes conflict between two government agencies. Rear Admiral Paul Friedrichs, head of the White House's Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy (OPPR), immediately set her sights on curbing the virus's spread.

The Department of Agriculture (USDA), led by Secretary Tom Vilsack, also took up the task — but with a different set of priorities. What unfolded was a stark clash of interests, revealing the tensions between safeguarding public health and protecting the powerful dairy industry.

Friedrichs and the OPPR laid out an ambitious response plan to confront H5N1 that reportedly included launching widespread on-the-ground studies of farms and infected animals. It involved working with farmers and state officials to gain access to outbreak zones and implement aggressive biosecurity measures. The goal was clear: to control the spread of the virus as quickly as possible.

It didn't take long for the OPPR to realize that the USDA was not on the same page.

Did the USDA thwart a quick response to the virus?

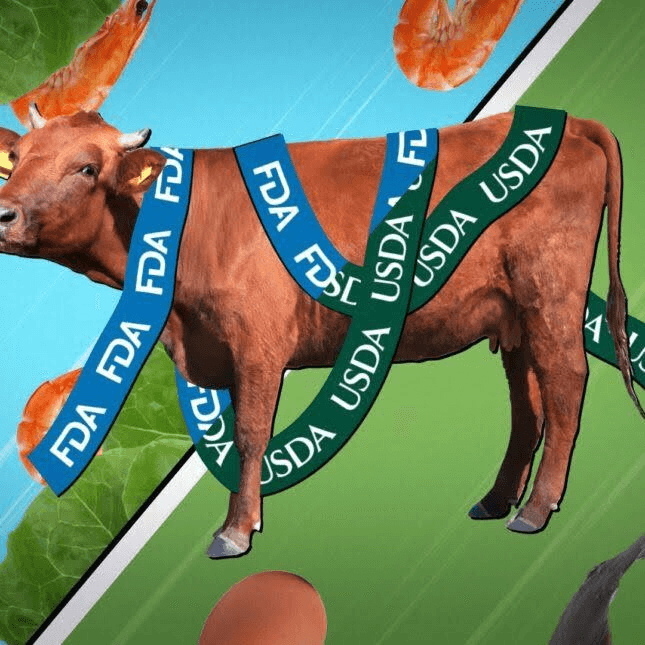

While the White House pushed for a response focused on public health, the USDA and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which share jurisdiction over the production, transportation, and storage of eggs, seemed more concerned with protecting the interests of the dairy industry. Dairy representatives worried that the virus and subsequent restrictions could cripple their business.

According to a former USDA official, dairy industry insiders were alarmed that White House staff were contacting them directly, bypassing the usual channels through the USDA. State veterinarians reported they were told to discontinue routine calls with the USDA's veterinary services. This exacerbated the communication rift between the White House and the USDA.

The USDA had historically relied on the cooperation of farmers and industry stakeholders, and the bureaucrats feared losing that trust. In contrast, the White House's OPPR and its public health allies grew increasingly frustrated as the USDA dragged its feet and adopted an approach that seemed to be, "If you don't test, you don't know." This tension and communication failures have come to define the fractured nature of the government's response to the H5N1 outbreak.

While the OPPR and the USDA were locked in a bureaucratic standoff, the virus was spreading. The response was mostly left to individual states to manage the fallout. Often, they were not up to it.

In late March, Texas state veterinarian Lewis "Bud" Dinges faced a critical decision: whether to halt the interstate movement of dairy cows to prevent further transmission of the virus. It was a straightforward public health measure — if you stop the cows from moving, you stop, or at least slow, the spread of disease.

Yet, for unexplained reasons, Dinges declined to act. Soon after, infected cows from Texas carried the virus to other states, worsening the outbreak. That appears to be clear malfeasance by Dinges, raising the question of whether he bent to industry pressure.

This was not the only instance of ignorance and irresponsibility in the state government in Texas. Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller, a vocal advocate for the dairy industry, dismissed the threat, downplaying the outbreak and claiming that it affected only a small fraction of cows in the state. He claimed that he didn't know anyone who had lost livestock. Miller's refusal to allow the CDC to test farmworkers for exposure reflected a broader resistance to federal intervention, further complicating efforts to contain the virus — yet another example of flagrant malfeasance in Texas's government. The USDA sat on its hands as Texas refused to act.

The conflict of interest between the agricultural industry and public health is built into the structure of the USDA. It is analogous to the department's dual but also incompatible roles in overseeing organic agriculture. It is charged with both promoting organic farming and setting industry standards and permissible practices. In recent years, as it became increasingly apparent that organic farmers were financially hard-pressed to follow the standards they had helped draft, they appealed repeatedly to bureaucrats to loosen the rules, and the USDA often complied.

Farmers, fear, and gaming the system

The USDA eventually issued a federal order requiring limited interstate testing of cows, but the response from farmers was lukewarm at best. Despite the growing number of infections, dairy farmers across the country hesitated to embrace testing and containment measures. Herds that moved between states often contained hundreds of cows, but the new testing mandate required only testing of a small sample: 30 cows. Even worse, rumors spread that some farmers were gaming the system by prescreening cows in private labs, ensuring that only healthy animals were tested before official samples were sent to the USDA. If true, that was deplorable, if not criminal, behavior.

The lack of comprehensive testing allowed the virus to continue circulating largely unchecked. In states that mandated testing of milk in bulk tanks, the outbreak was far more visible. In Colorado, for example, more than half of the state's dairy herds showed signs of infection. Other states, however, lagged in their vigilance.

California, the nation's largest dairy producer, became the next major battleground when cows transported from Idaho imported the virus. By October, 124 of California's 1,100 dairy herds had been infected, and the virus showed no signs of slowing.

As the virus continued to spread, farmers were reluctant to test their herds, fearful that a quarantine could destroy their businesses.

Veterinarians felt the stress of the outbreak. They found themselves buffeted by conflicting pressures from public health officials, farmers, and industry stakeholders. Fred Gingrich, executive director of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners, acknowledged their difficult position, with some veterinarians forced to choose between their professional ethics and the demands of the farmers they served.

The Fractured US food regulatory system

As the H5N1 outbreak has ravaged the dairy industry, public health officials, veterinarians, and farmers have been left grappling with the consequences of a fractured response. Researchers relied on data-sharing platforms like GISAID (the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data), a science initiative that is supposed to provide access to genomic data of influenza viruses -- in order to obtain timely warning of the appearance of new variants of concern -- but the USDA's submissions were often delayed and lacking in critical details. This failure to provide timely, actionable information hindered efforts to control the outbreak.

The USDA has defended its indolent approach, emphasizing the need for accuracy and thoroughness in its data collection. But critics within the public health community — of whom I am one — argue that the virus could have been contained early on. Instead, it continued to spread, fueled by inaction resulting from wrongheaded priorities at the USDA and a lack of unified leadership.

As the virus continues to evolve and spread (see Part 1 of this series), the consequences of this disjointed response may yet escalate, both for the dairy industry and for public health. As Part 1 ended:

The proximate question is whether this delayed and bungled response will lead to policy oversight reforms or whether we'll continue to play a dangerous game of catch-up.

A new development has made that game of catch-up both more difficult and more dangerous, as this October 31 headline and sub-headline in Scientific American make clear:

Bird Flu Is One Step Closer to Mixing with Seasonal Flu Virus and Becoming a Pandemic

Humans and pigs could both serve as mixing vessels for a bird flu–seasonal flu hybrid, posing a risk of wider spread

As the article explains, coinfection of an animal such as a pig with different flu viruses can lead to "reassortment" of pieces of the flu genome, which is comprised of eight RNA segments:

When multiple viruses infect the same cell and replicate, they can swap these segments, producing one of 256 possible combinations. This reassortment can create a virus that contains features of both parent viruses, which could make it more transmissible and virulent. The process is thought to have produced the 2009 H1N1 swine flu from a mix of U.S. and European strains of pig flu virus, launching a (thankfully mild) pandemic.

That frightening scenario becomes more likely as the virus spreads. On November 12th, British Columbia health officials announced that a previously healthy teenager was hospitalized in critical condition with the H5N1 flu. It was Canada's first locally acquired H5N1 infection.

The long-term question is whether U.S. government agencies and the officials who manage them will be permitted to operate under conditions that present a clear conflict of interest – that is, whether their first allegiance is to society's well-being or a narrow, commercial constituency. Congress needs to act before a virus reshapes the world's public health landscape.

An earlier version of this article was published by the Genetic Literacy Project.

Note: Much of the information herein was first disclosed by the excellent investigative reporting of Katherine Eban.