As Fox Sports reported in 2016, the average weight of a starting NFL linesman was 315 pounds, aggregating to over 25 tons for the 160 players – arguably, they are all fit. Of course, BMI is a particularly poor measure of fitness in these individuals as it cannot differentiate muscle weight from fat, and each tissue has a different impact on fitness. The scientific consensus has at least agreed that cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) has a stronger association with mortality risk than BMI. A new meta-analysis updates that data to be more inclusive of women.

The researchers considered studies since 1980

- That were prospective.

- CRF was assessed using VO2, the maximum oxygen a person can utilize during intense exercise. It is the gold standard for measuring cardiovascular fitness, reflecting the efficiency of muscle oxygen use and heart function during aerobic exercise - higher levels mean the body can use more oxygen to produce energy during exertion. [1]

- BMI was directly measured and reported.

- The joint impact of CRF and BMI was analyzed with a reference group of normal-weight, fit individuals. [2]

Of the 2279 articles identified, 20 met these criteria and formed the dataset that included 398,000 observations, 67% in males. The studies were deemed good “quality.” BMI was categorized as normal, overweight, or obese; CRF as fit or unfit. [3] This resulted in a reference group, normal weight-fit, and five comparison groups: normal weight-unfit, overweight-unfit, obese-unfit, overweight-fit, obese-fit

Results

- All-cause mortality - The study found that being overweight or obese but fit did not significantly increase the risk of all-cause mortality compared to being normal weight and fit. However, unfit individuals showed a higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to their fit counterparts. Moderation by sex, age, chronic disease status, and length of follow-up did not alter these findings.

-

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality – Being overweight or obese but fit did not significantly increase risk compared to being normal weight and fit. However, unfit individuals, whether of normal weight, overweight, or obese, had a substantially higher risk of CVD mortality. In this instance, the analysis had some important caveats in those categorized as obese-unfit, where the results covered a wide range. The results for obese-unfit individuals lost significance when one study was excluded.

Overweight and unfit individuals without chronic disease showed higher cardiovascular mortality compared to those with chronic disease, but all chronic disease data came from a single cohort, raising concerns about selection bias. Additionally, shorter follow-up studies indicated higher mortality risks than longer-term studies, suggesting follow-up duration may influence results and highlight limitations in the existing research. The researchers suggest that while fitness plays an important role in the short-term, given long enough time spans, “CRF is less protective due to general aging.”

The bottom line is that fitness plays a critical role in reducing all-cause and CVD mortality risk regardless of weight. However, there is a silver lining in the researchers’ cloud for those clinging to a belief in fat and fit. In a study using our old friend, the

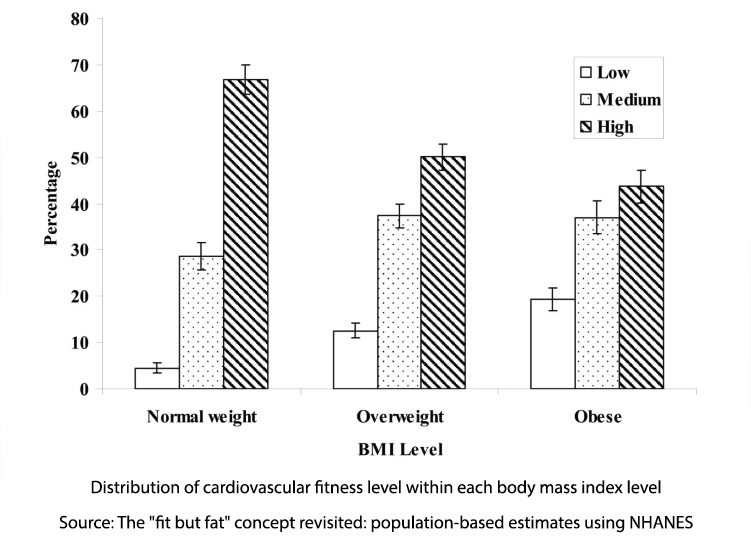

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), utilizing VO2 and BMI, it turns out that the “individuals at risk” reflected small numbers of the overweight, 12.5%, and 20% for the obese. These researchers sound a more positive note,

“These findings are somewhat encouraging because they demonstrate that overweight and obese individuals can achieve a medium to high cardiovascular fitness level, which could potentially mitigate some of the deleterious effects of excess body weight on health.”

Being unfit increased all-cause mortality 2-fold, and there was a greater increase for CVD. But, by the numbers, “individuals only needed to exceed the CRF of the study population’s 20th percentile in order to be considered fit.”

Exercise resulting in improved “fitness” can mitigate but not eliminate some of the harmful impacts of weight.

With the introduction of GLP-1s, weight loss has become much easier. Maintenance of weight loss has proven difficult. A meta-analysis done before GLP-1s indicated that 80% of individuals regained weight within 5 years. The early analysis of individuals stopping tirzepatide and semaglutide indicates that they regain weight, although the degree to which they do so remains unknown. Because of this, the researchers suggest that while not discouraging weight loss, solely weight-centric interventions are inadequate and that our health would benefit from a more CRF-centric approach. Of course, that ignores the “recidivism” rate from gym memberships, which is approximately 50% at six months

The findings suggest that it is possible to be fit and overweight or obese while mitigating some of the associated health risks, particularly cardiovascular disease. However, fitness alone cannot entirely eliminate the health impacts of excess weight. The research highlights the importance of focusing on both fitness and weight management.

[1] The predictive value of VO2 measurements can vary when weight is expressed as BMI, as is the case here, or as in fat-free mass, where the value will be higher. That is why those NFL players are more fit than might be suspected, looking solely at the numbers.

[2] Participants included individuals with “CVD, diabetes, renal disease, asthma, hormone replacement therapy, smokers, and chronic respiratory diseases.”

[3] The highest CRF in each study was categorized as fit, and the lowest was unfit.

Source: Cardiorespiratory fitness, body mass index and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis British Journal of Sports Medicine DOI: 0.1136/bjsports-2024-108748