Dr. Jeff Singer, a practicing surgeon and Senior Fellow at Cato Institute, and I have written about the Iron Law of Prohibition: As enforcement of drug prohibition increases, the potency of prohibited substances tends to increase. For the most part, the analogy has been dead on, as we've seen increasing overdose deaths beginning with the crackdown on prescription opioids then progressing to heroin, and around 2014, to fentanyl, which is still the primary culprit. More recently, we've seen new, scary drugs such as xylazine and nitazenes make inroads into the supply of illicit fentanyl.

Will the Iron Law reverse the modest decline (1) in drug deaths seen between 2023-4? History tells us, yes, and if a new trend – the addition of carfentanil to illicit fentanyl – catches on, things could get a whole lot worse. Why? The Iron Law plus a little biochemistry. Only this time it could be a double hit: a far deadlier drug and the real possibility that the only opioid antidote, naloxone, may no longer work.

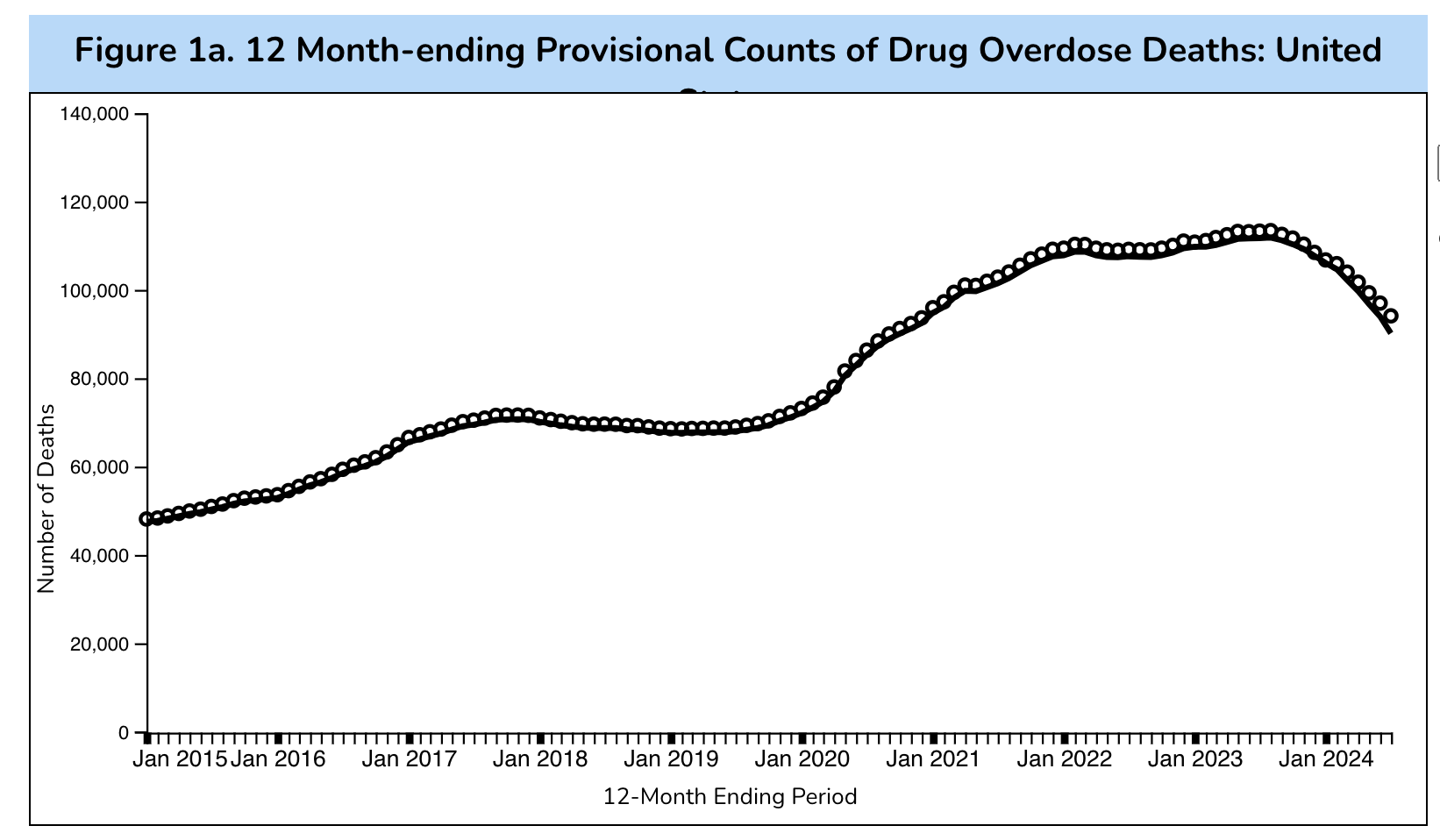

Figure 1. The decline in drug overdose deaths between mid-2023 and 2024. Based on data collected on 12/1/24. Source: CDC Provisional Overdose Death Counts

Fentanyl is bad, but "manageable"

One of the reasons given for the reduction in the number of deaths is the increased use of naloxone (Narcan), an opioid overdose antidote that works by blocking the opioid receptors in the brain where opioids reside (2). It does so because naloxone has a higher binding affinity than morphine, which gives it the ability to rapidly displace the drug from the receptor. Between 2020-22 there was a 43% increase in the administration of naloxone by laypersons. While naloxone use is undoubtedly part of the reason for the decline, it is not the only reason.

China has (finally) agreed to crack down on fentanyl precursor chemicals and there have been huge seizures of the drug by law enforcement, for example, in California, creating what could be perversely called a "fentanyl shortage." Supplies have gotten so tight that Mexican cartels have been recruiting chemistry students from colleges (with mixed success) to synthesize some of the precursors that are now difficult to obtain. The poor-quality fentanyl that is found in certain regions of the US may sound like "good news," but the opposite is true. This is because of what is added to make it stronger.

Carfentanil: The anesthetized elephant in the room

It's one thing to "cut" fentanyl with xylazine. Although the veterinary drug causes "severe necrotic skin ulcerations" and cannot be neutralized by naloxone (2) it's not as deadly as fentanyl itself. The same cannot be said for carfentanil – an elephant tranquilizer, which is now being found in fentanyl samples.

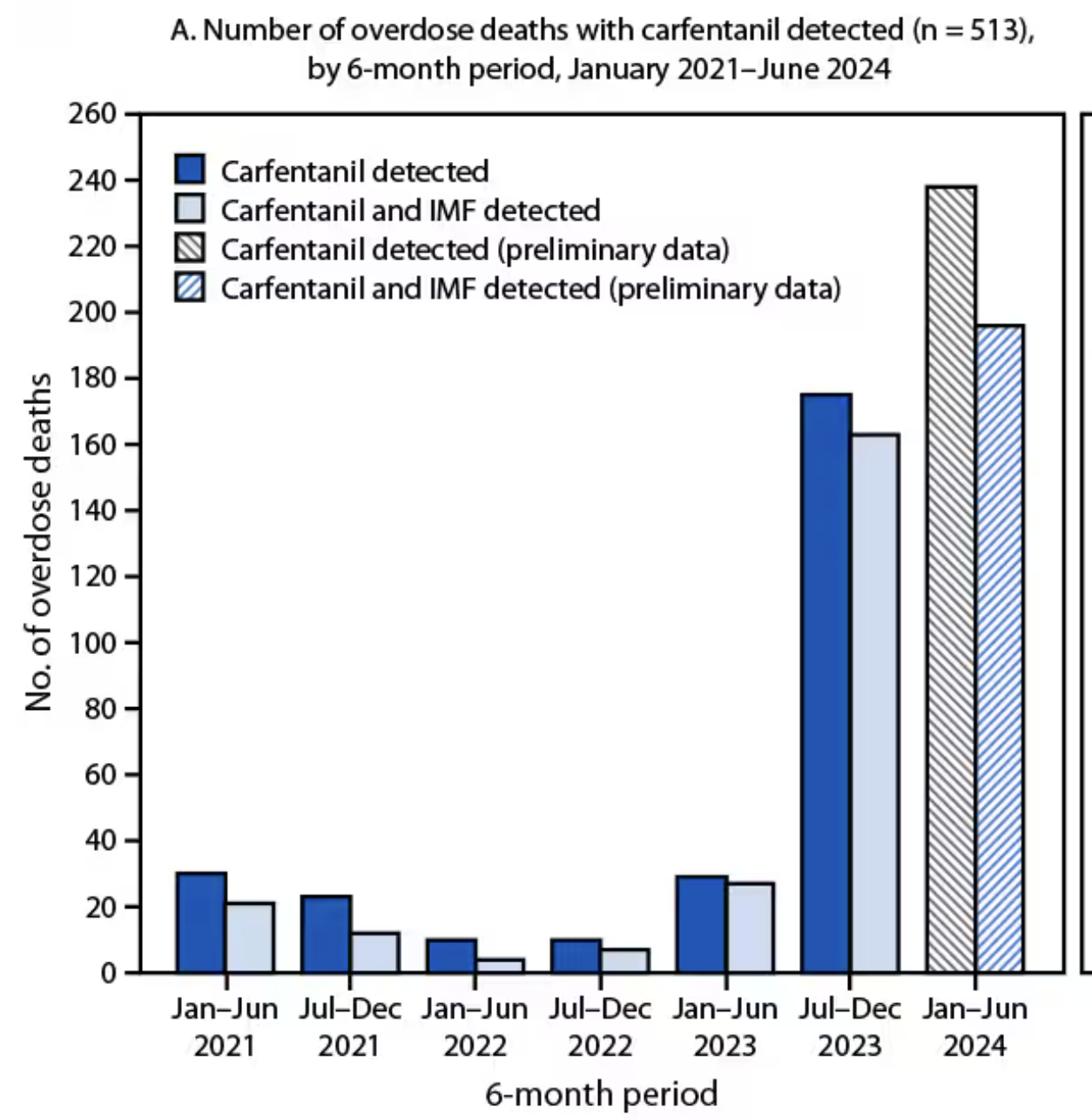

Figure 2. Although the number of deaths involving fentanyl samples that contain carfentanil is still small, the 720% increase in a short time is alarming. Source: MMWR, Detection of Illegally Manufactured Fentanyls and Carfentanil in Drug Overdose Deaths — United States, 2021–2024

Why carfentanil is so scary

To understand this we need to take a quick (and hopefully painless) look at binding constants. Please don't run away; it's not too bad.

A binding constant, also called an inhibition constant (abbreviated Ki), is a measure of the "stickiness" of a molecule to a receptor. The number represents the concentration to inhibit binding, the lower the Ki the more powerful the binding. For example, the Ki of morphine for the μ-opioid receptor is about 10 nanomolar (nM) while that of fentanyl is about 0.1 nM, roughly 100 times lower (stronger) that of morphine (3).

Using known Ki values we can construct a table that gives a rough idea of the relative strength of binding of four drugs to μ-opioid receptors:

Relative strength of drug binding to μ-opioid receptors

Morphine - 1 (weakest)

Fentanyl - 100

Naloxone - 100 (antagonist)

Carfentanil - 10,000 (strongest)

The problem with carfentanil should become obvious by comparing the binding strengths of the two. A dose of naloxone that will reverse the effects of morphine may not do so for fentanyl; a larger dose of naloxone is often needed. But with carfentanil, even the large doses required for fentanyl rescue are not sufficient. To make matters worse, the half-life of carfentanil is about 6 hours compared to about 1 hour for naloxone, meaning that the carfentanil will remain long after the naloxone is eliminated. So, large doses of naloxone must be given, as well as repeated doses. While this may sound "fine" in a hospital setting the problems in dealing with overdoses in other places should be obvious.

Bottom line

It is impossible to predict when and where the next, worse drug will emerge, the addition of carfentanil to fentanyl, should it become widespread, will become an instant, deadly problem. It's a truly evil drug and it is unlikely that we are prepared to deal with it. The Iron Law continues to reign.

NOTES:

(1) While opioid overdose deaths did decline other drugs like methamphetamine and cocaine continued to increase.

(2) Another reason is harm reduction in the form of fentanyl test strips.

(3) I use morphine as an example rather than heroin because heroin is metabolized before it reaches the brain, forming 6-monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM) and morphine, both active species. The metabolism complicates matters.