Alcohol has once again made headlines, this time with a warning that is likely giving industry executives sleepless nights. Dr. Vivek Murthy, the U.S. Surgeon General, has released an advisory titled Alcohol and Cancer Risk. In this article, we’ll examine the evidence supporting Murthy's findings and explore the chemistry behind alcohol's link to cancer.

Does alcohol cause cancer? Yes, it does.

The evidence that alcohol causes cancer is convincing. It has been linked to cancers of the oral cavity, throat, esophagus, liver, breast, colon, pancreas, and others in a dose-dependent manner. The Surgeon General's report estimates that alcohol consumption contributes to 100,000 cancer cases and 20,000 deaths annually, which represents about 3.5% of total cancer deaths – far less than deaths from smoking and obesity but still significant. (See a companion piece by Chuck Dinerstein for further insights.)

What makes alcohol carcinogenic?

It is not alcohol, but rather its primary metabolite acetaldehyde which is the carcinogen. The precise mechanisms of acetaldehyde's carcinogenicity (or that of any other chemical) are highly complex and well beyond the scope of this article. Here’s a simplified explanation.

Cancer typically begins with DNA damage, which involves chemically altering DNA, resulting in the disruption of cellular repair systems, and the formation of mutations. There are different types of DNA damage. Acetaldehyde is a potent electrophile [3] that reacts with nitrogen atoms of DNA nucleobase resulting in double-strand DNA breaks, the most severe form of DNA damage. (It also induces other forms of DNA damage.) Given the chemical nature of acetaldehyde as well as the documented DNA damage, the biochemistry of this interaction strongly supports acetaldehyde carcinogenicity.

Cancer warnings should make sense

In contrast, consider aspartame—a common artificial sweetener and a perpetual, but false cancer scare. In a 2022 article, Worrying About the Wrong Carcinogen: Alcohol vs. Aspartame, I concluded that aspartame poses essentially no carcinogenic risk whatsoever, especially compared to alcohol. Due to misguided public fears, the trace amounts of formaldehyde formed from aspartame’s breakdown are negligible compared to everyday exposures of the chemical from other sources [1] . Coke, either diet or sugared, is safer to drink than the rum that often accompanies it. But at least the aspartame scare makes some sense because of the small but insignificant amount of formaldehyde that is formed. The same cannot be said for the system that California came up with

Real, fake, and absurd cancer scares

Of the approximately 2,000 known or suspected carcinogenic chemicals [4], acetaldehyde belongs on the list due to its clear and well-documented effects [5]. Depending on the regulatory agency involved, acetaldehyde is classified either as a probable carcinogen or a known carcinogen.

The disconnect between the conclusions of (mostly) legitimate agencies and those listed those spelled out in California's insane Proposition 65 clearly illustrates this.

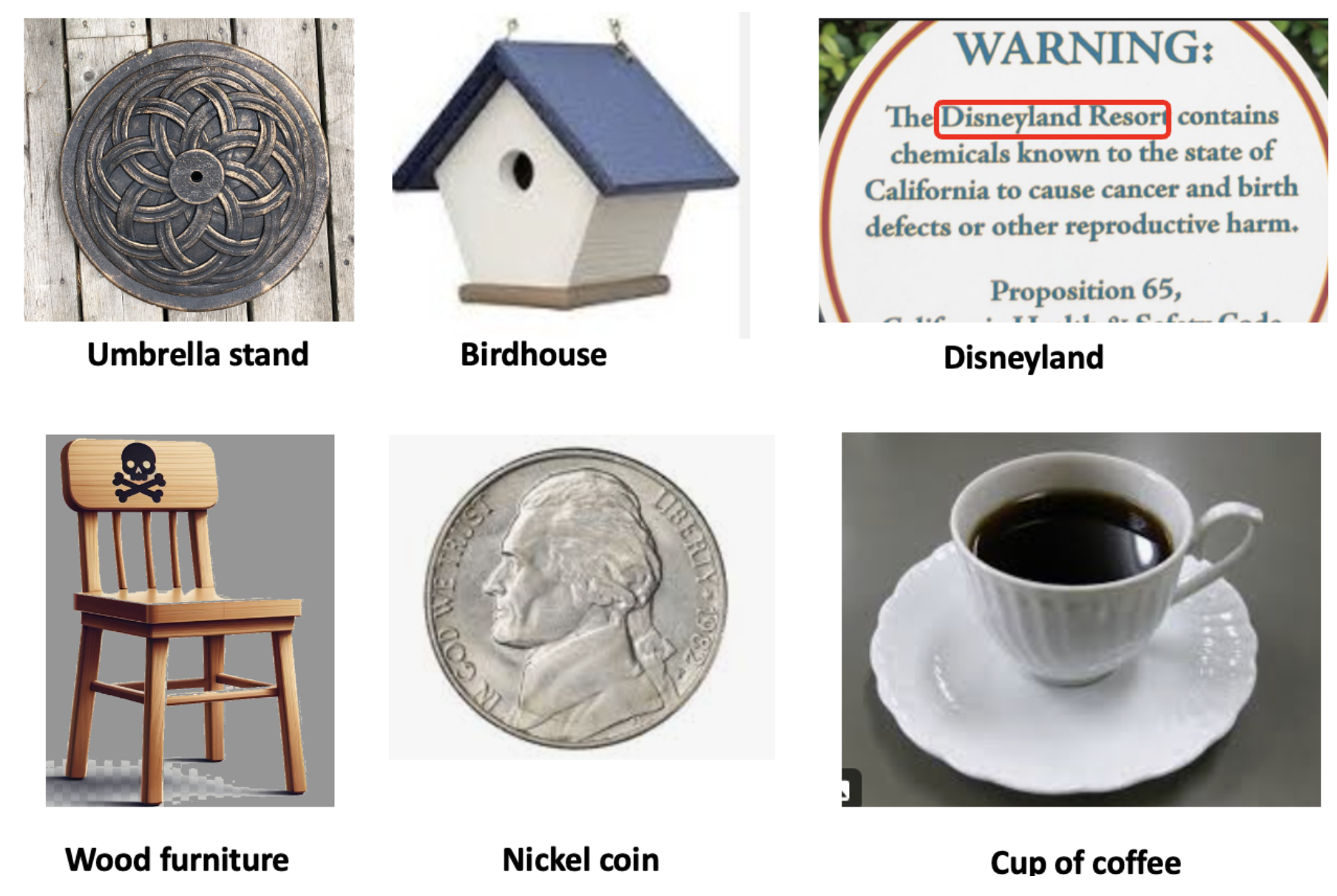

While the science-based classification of carcinogens should depend on data and logic, the same cannot be said for the mess that California has come up with, something I've written about recently. (See: In California, Coffee Both Causes and Prevents Cancer.) Here are a few examples of products in Prop 65 that must be labeled as carcinogens. I'm not kidding.

All of these items are carcinogenic, according to California's Proposition 65, and must therefore have warning stickers. The overarching message? Don't go to Disneyland. but if you must, don't bring any spare change, sit on a chair, or drink coffee. And make sure you leave your birdhouse and umbrella stand at home. And there are many more, for example, hotel rooms, airports, dental offices, playgrounds, and beaches. Madness.

Unlike the nonsense from California, the carcinogenicity of alcohol is real. But when "everything" causes cancer the message that the public "hears" is that nothing does. This is why it is important to have a sensible system that considers real risks, not hazards [6].

Bottom line: What will win? Science, silliness, or something else?

I apologize in advance for some supercharged cynicism. In my opinion, it will be something else: Money. In a perfect world alcohol absolutely should be held to the same standard as tobacco. Its ability to cause cancer has been proven by epidemiological studies and very detailed biochemical studies. Alcohol should carry a cancer warning label, much like cigarettes.

But don't bet on it. The debate over alcohol warning labels isn’t about science—it’s about money The alcohol industry is fighting this tooth, nail, and swizzle stick. It spent about $540 million on lobbying in the past two decades. How much of this went into politicians' pockets? You tell me.

It’s time for a sensible system that communicates real risks. Alcohol, like tobacco, should carry a clear cancer warning label. Or neither of them. Until then, the old saying “everything causes cancer” will continue to obscure the truth, leaving Americans uncertain about what to believe.

NOTES:

- These include tobacco smoke, fruits and vegetables, indoor air, cosmetics, plants, and microbes...

- Acetaldehyde is a bit less toxic and carcinogenic than formaldehyde, but the dose is important. When people drink their bodies are exposed to a constant, high level of the chemical.

- An electrophile is a molecule that reacts with atoms like nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen. Most electrophiles do this non-selectively, going after proteins and DNA. Most of them are toxic, some (nerve gases) extremely so.

- This number is probably meaningless because it includes both nonsense "carcinogens" and real ones.

- There are far worse carcinogens than acetaldehyde. It's merely bad, not hellacious.

- Hazard is the intrinsic potential of something (e.g., a chemical or activity) to cause harm, regardless of exposure, while risk is the likelihood that harm will occur based on the level and context of exposure. For example, acetaldehyde is hazardous because it is carcinogenic, but its risk depends on how much and how often someone is exposed.