Advancements in cancer treatments are neither frequent nor easy to acheive.

The movement over the last year that pushed immunotherapies into the realm of treatments for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and large B-cell lymphoma have marked a new future for the treatment of those cancers.

But, other cancers remain with far fewer treatment options.

New research published in Science Translational Medicine this week introduced a new potential treatment for some of the most difficult to treat cancers - brain and triple negative breast cancer (TNBC).

The research, published in two side by side papers, shows that viruses enhance the use of checkpoint therapy in cancer treatment. But, to understand how viruses help in treatment utilizing immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), we need first to understand what ICIs are.

Our immune system relies on its ability to distinguish self from non-self. This way, it can attack invaders (say, a bacterial cell that is causing strep throat) without attacking our own body (the cells in the throat.) This process relies on “checkpoints” which are molecules on some of our immune cells that need to be activated (or inactivated) to start an immune response.

The process of making this distinction becomes difficult for immune cells because cancer cells lie in a gray area of self and non-self. In addition, cancer cells can manipulate checkpoints to avoid being attacked by the immune system. One hot field of cancer research is to tweak this system so that cancer cells are more visible or recognizable to the immune system. In doing so, the immune system can be harnessed to target cancer cells and kill them. Drugs that target these checkpoints have held a lot of promise as cancer treatments.

And, anything that can help with this type of therapy is a welcome discovery - in addition to making this therapy applicable to types of cancers that it previously wasn't. It turns out that viruses may do this.

In both studies, the authors found that virus treatment given early, before surgical removal of the mass, alters the immune response and increases the effects of treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Bourgeois-Daigneault et al. discovered this for TNBC and Samson et al. for brain tumors.

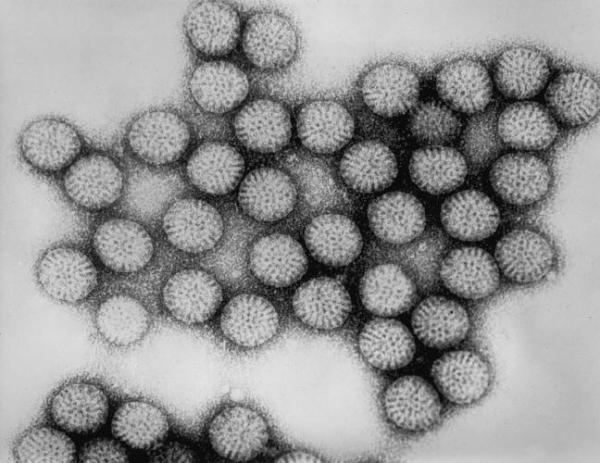

For TNBC, Maraba virus was used to promote antitumor immunity. For the brain, it was intravenous infusion of reovirus. The immune effects are different in each paper, but, the overarching finding is that viruses plus ICI did a better job than ICI alone.

It is important to mention that neither breast nor brain tumors are usually treatable with these drugs. So, in essence, these findings may have opened up an entirely new treatment option for these otherwise intractable cancers. For the people with TNBC (15% of all breast cancer patients) and brain cancer, it may be a lifesaver.