Mission creep occurs when there is continue growth in a project’s goals; often involving additional features adding cost and complexity. In New York City, school lunches are free to all students irrespective of income because, “hunger is the foe to education.” Similar programs are at work in Boston, Detroit, Chicago and Dallas. And when school ends for the summer, those New York City food programs continue year-round.

Schools are effective, convenient sites to help hungry children; but with an 80% graduation rate, albeit only 4% less than the national average, is feeding hungry children the role of the schools? Healthcare’s version of mission creep involves a similarly entangled problem, the socioeconomic determinants of health; and like the school food programs that are about to enter the mainstream.

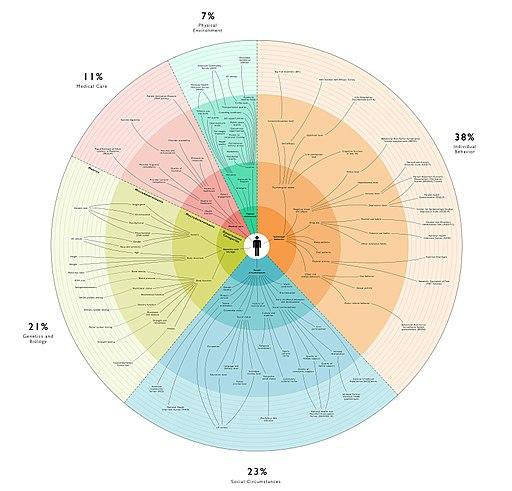

There are any number of epidemiologic studies that confirm the common sense view, that problems of education, employment, housing, transportation, our family and extended family support system, as well as environmental factors influence our health and ability to access care. In one study of veterans [1], homeless veterans had a 40% greater chance of being readmitted after inpatient surgery. Their inpatient stays were longer, more were sent to nursing homes and seen in the emergency rooms after surgery than veterans who had homes, even though this latter group had more medical problems. And you can find similar findings for transportation, health literacy, and family/friend support.

In the changing world of healthcare payments, more money is provided to cover the greater cost of caring for patients at bigger risk, for example Medicare Advantage programs receive more monies from the federal government for those with more physical ailments, comorbidities, than those who are healthy. Again, it seems perfectly obvious.

This medicalization of socioeconomic determinants of health is highlighted by an announcement last week that the American Hospital Association, the American Medical Association, and United Healthcare all are promoting the standardizing the documentation of these conditions through the use of ICD-10 codes.

The codes [2] have existed for some time, languishing in disuse because physicians, who are the only “providers” able to document, e.g. to certify diagnostic information are more involved with a patients direct health concerns, leaving finances, homes, transportation, and literacy all factors influencing outcomes to those on the team focusing on discharge care – nurses and social workers. The American Hospital Association has changed their rules and now these codes for socioeconomic determinants can be documented by them.

United Healthcare has begun using these codes for its Medicare Advantage beneficiaries and in 2017 through 2018 made over 500,000 social service referrals for additional care based upon those codes. [3] In partnership with Mom’s Meals [4], they provided 2.5 million meals. Like the schools, insurance companies and hospitals may well be efficient sites to identify need, but are they the ones to resolve the problem?

A cynic would argue that all three of these endorsers have conflicted interest. The American Hospital Association and United Healthcare are paid more for patients at risk, so coding these socioeconomic risks not only recognizes their roles in our health, but in the health of their bottom lines. In the words of one of United Healthcare’s executives, “We know there is a business case to be made…” The American Medical Association continues to earn most of its income from the development and promulgation of diagnostic and procedural codes.

Socioeconomic determinants are important and many health encounters, not just hospitalization, present opportunities to identify these issues and make appropriate referrals for additional supportive services. Adding these risks into healthcare’s primary bucket of concerns continues the process of moving healthcare from treating disease to prevention and wellness. Integrating services is a two-edged sword, it does create one-stop shopping but it does risk diluting the focus. Do you want multi-tasking or mindfulness?

[1] Homeless Status, Postdischarge Health Care Utilization, and Readmission After Surgery Medical Care DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000915

[3] Why UnitedHealthcare wants to expand diagnostic codes to social determinants of health Fiercehealthcare