Roughly two dozen elements are named after people or places. You know some of them... curium, einsteinium, livermorium, nobelium, etc. Most of these elements are "ghosts" – they don't really exist. You can't wander into Macy's and buy a livermorium tie pin for Father's Day. It is a synthetic element – one that is found nowhere in nature. These elements are created by putting something-or-other in a particle accelerator the size of Newark and blasting it with a whole bunch of high-energy whatchamacallits.

This particle storage ring at the Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research in Germany helped scientists make a minuscule amount of tennessine, which stayed around for a small fraction of a second. Every kitchen should have one. Photo credit: J. Mai/GSI/Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research/Discovery Magazine

Unlike synthetic elements, minerals are real. You can dig 'em up and put 'em in your pocket. But minerals have a very different naming system from the elements and also chemical compounds, which have their share of bizarre names as well. The names of most minerals end in -ite, from the Greek word lithos (from its adjective form -ites), meaning rock or stone. In order to add some semblance of consistency to mineral names, "ite" was added, e.g., azule became azurite.

This is Where the Fun Starts

1. (Cu,Zn)16(TeO3)2(AsO4)3Cl(OH)18 · 7H2O

This beautiful mineral was discovered at a dump at a mine in Eureka, Utah. It is unclear whether the discoverer was suffering from any gastrointestinal issues at the time. But you can't blame anyone for making this assumption. Eurekadumpite does evoke – except perhaps in the purest of minds – an image of some guy who is gleefully celebrating his accomplishment having not dropped a bomb in two weeks.

.

.

Eurekadumpite. Photo credit: Wikipedia

2, 3. Cu(C2O4) · 0.4H2O and Ca[Al2Si6O16] · 5H2O

Although these are neither juvenile nor obscene, the following minerals get props, if only for the odd names. Moolooite (left) was discovered at Mooloo Downs Station in Australia. And goosecreekite (right) was named after the New Goose Creek Quarry in Virginia, which makes me wonder what happened to Old Goose Creek Quarry.

(Right) Moolooite. (Left) Goosecreekite. Photo credits: Wikidata, Wikipedia

4. Al2Si2O5(OH)4

This particular mineral was named after its discoverer rather than its location. In 1888 a metallurgist with the rather unfortunate name Allan Brugh Dick discovered a new clay mineral. Years later, scientists would name it after Mr. Dick. (Like it's not bad enough to have the last name "Dick," let alone have dickite be your legacy?) I shall not comment on the relative hardness of dickite; that would be unprofessional.

Dickite. Photo: Wikimedia

5. Ca4Si2O6(CO3)(OH)F

While the mineral below may look rather ordinary, the same cannot be said of its name. Anything discovered in the Fuka Mine in Japan has the potential to stir up trouble, but the actual pronunciation of fukasite is Foo-kah-site. The name is first reported in 1999 in an article titled "New Mineral Names" in the journal American Mineralogist. Interesting factoid: Collecting this stuff is prohibited, except for researchers associated with Okayama University.

Fukasite. Photo: Flickr

Saving the best for last...

6. (Mg,Fe2+)2(Mg,Fe2+)5Si8O22(OH)2

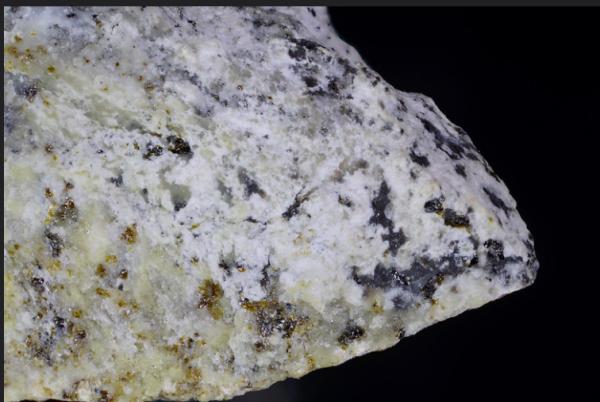

It was 1824, and our language had not yet devolved into its present form. So, you can probably forgive the name of a mineral discovered in the town of Cummington, Massachusetts (which itself is bad enough):

Cummingtonite. Its name is golden, just like the mineral. Photo: Wikipedia

I've had enough, so let's just call this a happy ending.

NOTE:

In case any of you need more idiocy in your life there is a site that has even more crazy-sounding minerals.