Debates regarding healthcare policy in America inevitably lead to discussions over exorbitant costs, and discussions over exorbitant costs inevitably lead to blame. The problem is that nobody in the healthcare ecosystem takes the blame; it’s always somebody else’s fault.

This blame game was on full display in an op-ed published in the Journal of the American Medical Association titled, “Salve Lucrum: The Existential Threat of Greed in U.S. Health Care.” Who is excessively greedy? According to the author, drug companies, insurance companies, hospitals, and healthcare executives. In other words:

Credit: ACSH / imgflip

Absent from the op-ed was the fact that American doctors earn far more than their colleagues in peer countries. A recent survey found that doctors in the U.S. earn 220% more than the French, 129% more than the British, and 73% more than the Germans. The same survey found that the average physician in the U.S. had a net worth of $1.7 million, higher than the French (310%), Germans (295%), and Brits (165%).

A study from Stanford corroborated these findings. It found that “more than 25% of physicians in 2017 earned above $425,000 annually, and the top 1% of physicians averaged $4 million in annual earnings.” The average doctor made $350,000. And a report by the Commonwealth Fund, which investigated how excess healthcare dollars are spent, blamed (among several other things) doctor’s salaries:

“More than half of excess U.S. health spending was associated with factors likely reflected in higher prices, including more spending on administrative costs of insurance (~15% of the excess), administrative costs borne by providers (~15%), prescription drugs (~10%), wages for physicians (~10%) and registered nurses (~5%), and medical machinery and equipment (less than 5%).”

In response, doctors usually say, “Don’t blame us,” and point to other causes. (See meme above.) Indeed, a press release for the aforementioned Stanford study said that doctors’ earnings are responsible for “only” 8.6% of healthcare spending. Only? To put that number into perspective, prescription drugs — which everybody blames for high healthcare costs — are responsible for “only” about 10% of healthcare spending in America. So, yes, doctors’ salaries are very much a part of the problem.

The reason for high salaries

But why are they so high? I asked one of my best friends from childhood, who became a doctor, and she provided some crucial insights:

- Medical school (and education in general) is more expensive in the U.S., so American doctors have gigantic loans to repay.

- American lawyers can strike it rich by suing doctors, so malpractice insurance is expensive.

- There are higher expectations of doctors in the U.S., such as seeing more patients (when a nurse would have been sufficient) and being on call 24/7.

- Many doctors are leaving the practice due to burnout.

- There are too few medical schools and residency programs.

Those latter two points have conspired to create a doctor shortage. But this is really strange. Though it can indeed be a grueling job, why can't a profession that commands $350,000 salaries entice enough people to join it?

Is the doctor shortage intentional?

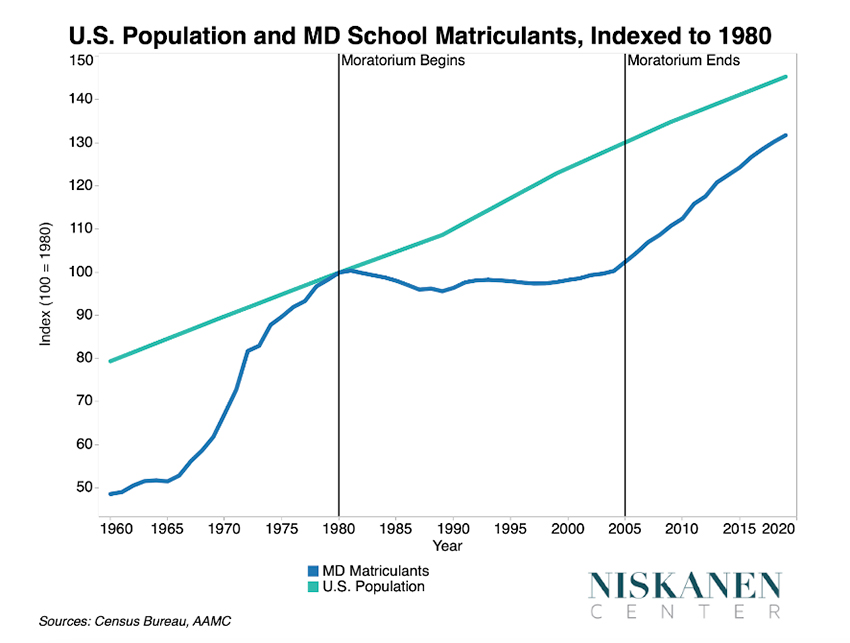

An analysis from the Niskanen Center sheds light on the issue. From 1980 to 2005, there was a widespread (and, as it turned out, false) belief based on an influential government report that a looming doctor surplus was on the horizon. Instead of letting the free market take care of the (as it turned out, non-existent) problem, the government and academia intervened. Federal financial support for training doctors decreased, residency requirements increased, and medical schools implemented a moratorium on increasing enrollment. Thus, as the American population grew, the number of new doctors flatlined.

Credit: Niskanen Center

Today, the same medical organizations that fretted over a (fake) doctor surplus are now sounding the alarm over a (real) shortage and denouncing inequality in access to healthcare — an inequality they helped create by artificially capping the number of students who could be trained as doctors.

Worse, as the Niskanen report details, the U.S. opened very few new medical schools from 1980 to 2005, meaning we lack the infrastructure to ramp up education to the level we need. And the U.S. government, specifically Medicare, continues to underfund the residency programs required to fully train doctors.

What about importing foreign doctors? We make that artificially complicated, too, so that a well-trained doctor from another country has to start all over again as a resident. As Vox explains, “The chief of surgery at the fanciest hospital in India would still have to repeat residency in order to practice in the U.S.”

To summarize: (1) The U.S. capped medical school enrollments from 1980 to 2005; (2) Medicare continues to this day to limit the number of residency slots available; and (3) We refuse to make it easier for foreign doctors to practice in the U.S. As The Economist concluded, “This looks a lot like a labor market that has been rigged in favor of the insiders.”