In other words:

“Do we need diet books and programs that instruct us to eat fruits and vegetables, moderate refined sugar and alcohol, or nutritional coaches who scare their audiences on social media with lists of allowed and prohibited foods?”

Obviously, the answer to both questions is a resounding no. However, this doesn’t stop an increasing number of self-proclaimed health experts from pointing the way—often with a link to purchase their consultancy or products—toward healthy eating.

In recent years, especially on social media, we’ve seen claims such as the low-carb diet is ideal for weight loss, intermittent fasting is the best for longevity, the carnivore diet can cure psychiatric disorders, and the vegan diet can save the planet, and even alleviate migraines.

While I would love to delve into the details behind each of these claims, the main focus of this article is a not-so-new industry trend: diets based on your genetics derived from DNA testing. In a word, nutrigenetics

How are these tests supposed to work?

Typically, the consumer orders the test online, collects a saliva sample and sends it to the company. The company extracts DNA from the sample and analyzes it for genetic variants linked to an increased risk of disease, regulation of specific traits, or health conditions. Among the services most commonly offered by these companies are genetic kits related to physical fitness (such as sports performance and injury risk), pharmacogenetics (personalized medication treatment), and nutrigenetics (weight control, food intolerances, and sensitivities).

According to a review published in 2020, nutrigenetic tests aim to act as a compass, guiding users to make more informed and healthier decisions.

“Standard nutritionon guidelines are based on the average population and are used to prevent deficiencies, not to optimise personal fitness levels, health and wellbeing. You are unique, your nutrition (diet) should be too.”

However, this assertion blurs the line between science and marketing.

For example, Nutri Genetix, a company that markets these tests and develops personalized food shakes based on the genetic results—what I would call a double win—claims its tests are grounded in nutrigenetics. This emerging field explores how genetics influence the processing and metabolism of various nutrients.

They promise that their test results can:

- Reveal, based on your genetic variations, your ability to use, process, and absorb different nutrients (such as caffeine and sodium).

- Indicate your specific needs for various micronutrients (vitamins and minerals).

- Assess the amount of endogenous antioxidants you can produce.

- Identify which macronutrient (fat, protein, or carbohydrate) is most likely to cause weight gain.

- Detect food allergies.

There is some truth to these claims, at least for caffeine, whose metabolism is primarily influenced by an enzyme called cytochrome P-450. Genetic variations in this enzyme can alter its activity, accelerating or slowing metabolism. A systematic review published in Nutrients investigated how single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [2] impact habitual caffeine use and the ergogenic and anxiogenic effects of caffeine. The review found strong evidence that SNPs in the three genes are associated with habitual caffeine consumption.

Although there is substantial evidence on how genetic variability impacts caffeine metabolism, this doesn’t necessarily mean other substances will be similarly affected by genetic polymorphisms related to their metabolism. By assuming genetics is the foundation for personalized nutrition, these nutrigenetic testing often fails to distinguish between well-established research and preliminary studies requiring replication and quality evaluation. Selling nutrigenetic testing frequently makes hasty generalizations, drawing a conclusion from a small or unrepresentative sample and false analogy where two situations share superficial similarities but have significant and relevant differences.

What is the evidence for weight loss?

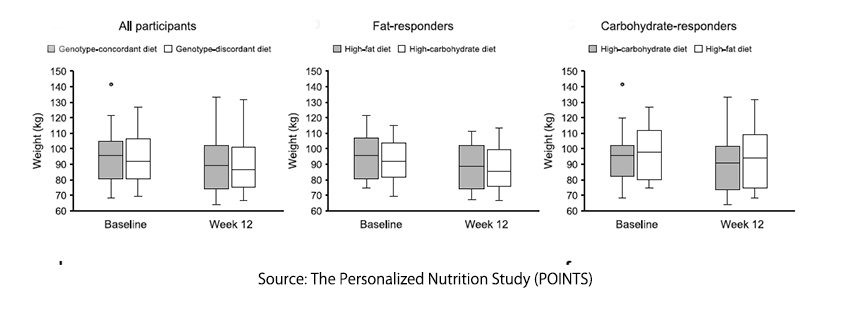

To address this question, a randomized clinical trial published in Nature Communications tested the following hypothesis: Would participants assigned to a diet tailored to their genotype (responders to fat or carbohydrates) lose more weight over 12 weeks than those assigned to a diet not aligned with their genotype?

Participants were aged between 18 and 75 years, non-smokers, overweight (BMI between 27 and 45 kg/m²), and no conditions or medications impacting body weight or metabolism. They were stratified by a genetic predisposition based upon the characterization of 10 SNPs, favoring diets rich in carbohydrates or fats.

Out of 145 recruited and randomized participants, 16 were lost to follow-up, and 7 were excluded due to genotyping errors or missing weight data. Therefore, the final analysis included 122 participants, who were randomly assigned to either a high-fat or high-carbohydrate diet and divided into four analysis groups:

- Fat responders receiving a high-fat diet

- Fat responders receiving a high-carbohydrate diet

- Carbohydrate responders receiving a high-fat diet

- Carbohydrate responders receiving a high-carbohydrate diet

The average age was 54.4, with a BMI of 34.9, classified as Grade 1 obesity, predominantly female and Caucasian, with a higher prevalence of a fat-responding genotype. Both diets were designed to create a caloric deficit of 750 kcal, reducing weight by about a little more than a pound weekly. The only difference between the diets was their nutritional composition; the high-carbohydrate diet got 20% more calories from carbs, and the high-fat diet got 20% more from fat.

During the 12 weeks of intervention, volunteers participated in weekly group sessions covering various food-related topics, from meal planning to behavioral changes. Participants were instructed to weigh themselves daily and send photos of their weight to the interventionists before each session. Although the sessions were initially planned to be held in person, most were conducted remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

- Weight loss did not differ between diets aligned with the genotype and those not. Fat responders' weight change was similar on both the high-fat and high-carbohydrate diets. The same pattern was observed among carbohydrate responders.

- There were no significant differences in body fat and anthropometric measurements, such as hip and waist circumference, between genotype-concordant and genotype-discordant diets.

- Changes in hunger, satisfaction with the intervention, and food desires and preferences did not differ between concordant and discordant diets.

Based on these findings, the authors wrote

“We found no difference in WL [weight loss] between individuals on the genotype-concordant vs. genotype-discordant diet.”

Among the most evident limitations of the study are three key issues:

- There were challenges in participant adherence. 39% in the high-carbohydrate diet and 66% in the high-fat diet followed the recipe and diet preparation they were asked to follow.

- The sample size was small, limiting the detection of small but significant clinical differences, i.e., body fat.

- The authors acknowledge that the genetic algorithm used to classify individuals as fat or carbohydrate responders was based on retrospective and modest-size studies that might result in false positive stratification.

Finally, there are two points to consider, although they do not alter the results found. First, the “high-fat” diet contained more carbohydrates than fat, which suggests that participants with a fat-responsive genotype did not receive an adequately tailored intervention. Second, there is a potential conflict of interest. Two authors are shareholders and employees of Weight Watchers, which does not currently offer or believe in the value of genetic testing for weight loss.

Does this mean the findings are unreliable? Not necessarily. However, these factors underscore the need for caution in interpreting the results and highlight the importance of awaiting future trials to confirm—or refute—the validity of these findings.

The bottom line is that although nutrigenetic companies present themselves as scientific, their aggressive marketing is filled with anecdotal consumer experiences. We currently lack robust evidence supporting the efficacy of nutrigenetic testing for weight loss. Until new evidence emerges, I recommend avoiding spending your hard-earned money on these products that, at best, promote weight loss, not by offering tailored ‘foods’ to help lose or prevent weight gain but by simply imposing a calorie-restricted diet.

[1] This insight is described by the authors, microbiologist Natália Pasternak and journalist Carlos Orsi.

[2] SNP are genetic variations in a single base-pair in the DNA sequence.

Sources: The Personalized Nutrition Study (POINTS): evaluation of a genetically informed weight loss approach, a Randomized Clinical Trial. Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-41969-1.

Genetics of caffeine consumption and responses to caffeine. Psychopharmacology. DOI: 10.1007/s00213-010-1900-1.