A review article in Circulation has forecasted an ever-increasing burden of cardiovascular disease in the U.S. for the next 25 years. The American Heart Association’s (AHA) goal, set in 2010, to

“By 2020, to improve the cardiovascular health of all Americans by 20% while reducing deaths from cardiovascular diseases and stroke by 20%.”

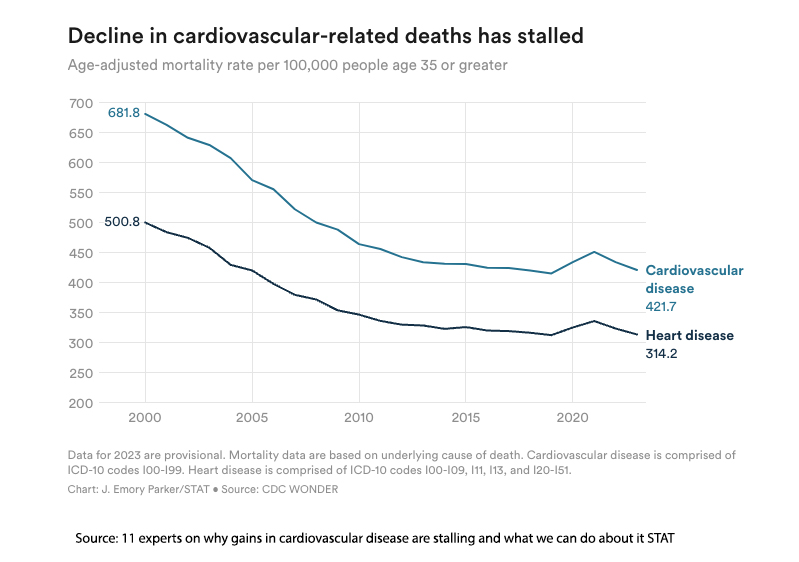

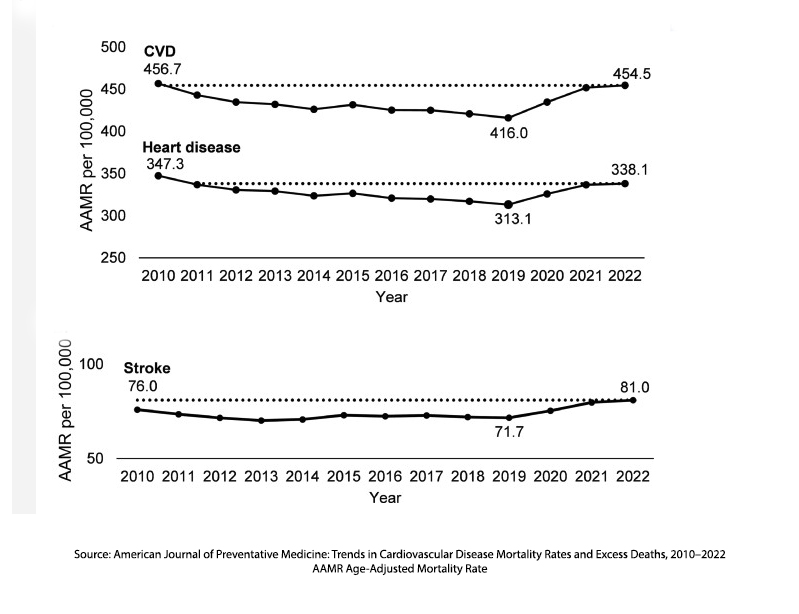

As STAT notes in their special report, that goal has not been fulfilled.

While the declines over time have been considerable, the trend seems to have flattened, stalled in STAT’s description, ever since the AHA’s  proclamation. Part of that is an “accounting” error, in that more individuals are surviving cardiovascular disease (CVD) and adding numbers to CVD’s longer-term sequelae, like heart failure. STAT’s experts offered a range of explanations, beginning with the fact that there is no single solution. [1]

proclamation. Part of that is an “accounting” error, in that more individuals are surviving cardiovascular disease (CVD) and adding numbers to CVD’s longer-term sequelae, like heart failure. STAT’s experts offered a range of explanations, beginning with the fact that there is no single solution. [1]

- Prevention is critical and starts with better access to healthcare, especially through primary care.

- Instilling healthy habits is difficult. “Patients themselves know that obesity is bad. Patients themselves know that high blood pressure, high cholesterol is bad, but they just don’t take on active participation until they’re sick.” - Clyde Yancy, chief of cardiology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

- GLP-1 drugs show promise beyond diabetes and weight loss but are expensive and have unequal access. Cheaper alternatives include a daily "polypill" combining multiple generic drugs for heart health and dietary reductions in trans fats and salt.

- Structural barriers, especially in African American communities, contribute to worse health outcomes. “A lot of my patients don’t live in neighborhoods that have sidewalks, or they don’t live in neighborhoods where there is a park or a recreation center for people to be out at safely,” she said. “If we don’t give people access to the kind of spaces that they need to do the physical activity that we recommend, then I think we can’t be surprised when we don’t get those types of results.” - Ann Marie Navar, a preventive cardiologist at UT Southwestern.

- Systematic lack of investment in primary care and incentives for acute care over prevention worsens the problem.

- To improve heart health, collaboration among all stakeholders, including patients, families, doctors, insurance companies, and hospitals, and incentive programs are needed.

Of course, all of these have been mentioned in the past and will be raised again in the future.

“We really do need to discover more about preventing disease earlier on. We’re still using fairly crude measures, targeting high blood pressure, targeting diabetes. It’s got to be something even more central.” [emphasis added]

- Clyde Yancy, chief of cardiology at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine

"When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure" - Goodhart's law

Goodhart’s law comes from economics and today is most often employed in the discussion of modeling. In healthcare, the AHA guidelines have included a range of measures, but cholesterol levels have been embraced by physicians, health organizations, and, importantly, payers. They are easily measured, and there is little doubt that lowering cholesterol levels has improved CVD. However, cholesterol levels are a proxy object for the outcome we are trying to optimize: reductions in CVD.

As with all modeling, as we optimize the proxy object, in this case, continuing to emphasize and lower cholesterol levels, we see initial improvements as demonstrated in those reductions in CVD mortality from 2000 to 2010. But at some point, Goodhart’s Law kicks in, an overfitting occurs. Overfitting is when a model works quite well with its training data, but fares poorly with new data, like cholesterol working well as a crucial marker in the past, but not so well today. The AHA guidelines, when updated in 2013, tried to be more holistic, setting aside using cholesterol levels and instead identifying risk groups.

But the payers, including both the government and the private sector, find numbers easy to capture and use in enforcing their goals with incentives and penalties. They fail to know or remember another version of Goodhart’s law.

“Any statistical relationship will break down when used for policy purposes.”

Modeling researchers have identified several means to reduce the effect of overfitting, which causes declining performance. Several stand out as germane in healthcare.

- Better align proxy goals with desired outcome: The AHA has tried combining LDL levels with other factors, such as diabetes or age, to create risk groups with more specific LDL goals. The difficulty lies with measuring those more complex proxies.

- Increase capabilities or capacity: These are the concerns captured in those experts’ comments on structural barriers, access, and promoting primary care and prevention.

As we wait for our institutions to recalibrate, we can follow the AHA's simple advice, as stated by STAT.

“Exercise, eat a healthy diet. Don’t smoke. Get plenty of sleep, get your weight under better control. Control your cholesterol, control your blood pressure so that you don’t get a heart attack or a stroke or kidney failure. And control your glucose.”

What’s the grand takeaway after years of optimizing our cholesterol? Maybe cholesterol isn’t the only number we should be chasing.

[1] You can find more of the expert’s views here in STAT’s, Heart disease experts in their own words

Sources: 11 experts on why gains in cardiovascular disease are stalling and what we can do about it STAT