“The indigenous peoples of North America, including New England, had a rich history of gambling long before European colonization. European settlers also brought their own gambling traditions, …In colonial America, lotteries were used to fund public works…”

So begins SEIGMA, the Social and Economic Impacts of Gambling in Massachusetts study, commissioned by the State to investigate the impact of casinos on the state’s economy and culture. Massachusetts has a long history of gambling:

- Horse and dog racing were legalized in 1934 to boost agriculture and generate revenue. Simulcast wagering began in 1983, allowing bets on out-of-state races.

- “Beano” (bingo) was legalized in 1934 to support charities, banned in 1943 due to crime, and re-legalized in 1971. Bingo participation peaked in 1984 with spending of $180 million; in 2016, residents spent $59.5 million on charitable gambling.

- The Massachusetts lottery was reestablished in 1971 to fund local cities and towns. By 2017, residents had spent over $5 billion, making it the highest per capita lottery in the US, with a payback rate of over 75%.

- Massachusetts legalized fantasy sports in 2016, followed by sports betting in 2022. As of January 2024, in-person betting is available at three casinos and ten online sites offer mobile betting.

Neighboring states offered casino games and electronic gaming machines; however, in 2011, Massachusetts legalized casinos, providing a before and after dataset underlying the SEIGMA study.

The Good

One of the usual selling points for casinos are economic growth and employment. There are the initial, transient economic boosts from casino construction and the longer-term boosts from casino operations.

- Casino Construction created significant benefits primarily for Massachusetts residents and host communities. There was $2.8 billion for construction jobs and an additional $2.2 billion in net new activity from casino construction.

- Casino Operations support 4,400-5,000 jobs, with $270.5 million in annual wages. However, those numbers come with two significant caveats. 75% of those employees went to the casinos from “other full-time roles,” and the number of jobs created rather than shifted is significantly lower. More critically, only 39% of those employees earn a living wage for their area. Sociodemographic changes varied between the three casino sites without any consistency. For example, there were increases in business along with declines in the food and beverage sector as the casinos cannibalized their customers, overall job growth, and some population growth.

In addition to more jobs, there is the increase in revenue to the State through taxation, specifically on the Gross Gaming Revenue (GGR). The casino’s GGR totaled around $1.1-1.2 billion annually, supplemented by non-gaming revenue of approximately $321 million annually. [1] Casino tax on GGR provided $78 million in FY2016, growing to around $330 million in FY2023, with funds benefiting cities, towns, and state programs. Lastly, the report mentions that casinos have the additional benefit of providing additional entertainment options for residents.

The Bad

As the history of gambling in Massachusetts has shown, there are strong societal forces opposed to gambling that have held sway at times, prohibiting the practice, although it appears that the tide of history is not on their side. A rise in crime is a salient concern; after all, bingo was prohibited at one point because of how it attracted a criminal element.

Statewide crime rates were stable, although illegal gambling offenses rose slightly. Specific types of criminal behavior, e.g., theft, fraud, and prostitution, rose around casinos, although in the host communities, property and violent crime followed the statewide trends downward. Traffic increased in all casino towns, leading to more accidents, impaired driving, and noise complaints.

Another concern is the impact of casinos on gambling behavior. Illegality is an ineffective hurdle, but a hurdle nonetheless, to gambling. Legalization removes that hurdle entirely. The argument around the legalization of gambling also holds for the discussion of the legalization of drugs, particularly marijuana, and the age restrictions we put on vaping, drinking, and, yes, gambling.

As hoped for, casino patronage increased within Massachusetts, while out-of-state casino visits declined, especially in areas near new casinos. Participation in most other gambling types remained steady, with minor declines in lottery and traditional forms but an uptick in online gambling. [2]

The Ugly, F63.0

F63.0 was the medical code for pathological gambling, what we might call a gambling addiction, and what the SEIGMA report refers to as “problem gambling.” Interestingly, pathological gambling was not lumped in with substance use disorders, although they share the same behavioral characteristics, because there was no physically addictive component. The most recent version of the Diagnostic & Statistics Manual reclassified F63.0 as gambling disorder (GD), altering the criteria to make it more inclusive. [3]

By whatever name you choose to use, GD has a very low prevalence, at around 3%, but those with the disorder frequently have problems with alcohol (41%) or other substances, including nicotine (21%). Interestingly, according to one study, the heritability of GD is equivalent to the heritability of opioid use disorder, although our societal response to the two conditions is quite different. At-risk gamblers, with a prevalence of about 5%, do not meet all the current criteria.

SEIGMA reports that problem gambling rates and demographics largely stayed the same, though gamblers seeking treatment decreased. Personal bankruptcy filings and adverse family impacts did not rise, nor did suicide rates. However, the share of casino revenue from at-risk/problem gamblers grew significantly. A significant portion of casino revenue (90%) comes from at-risk and problem gamblers, a concerning reliance.

The Indifferent

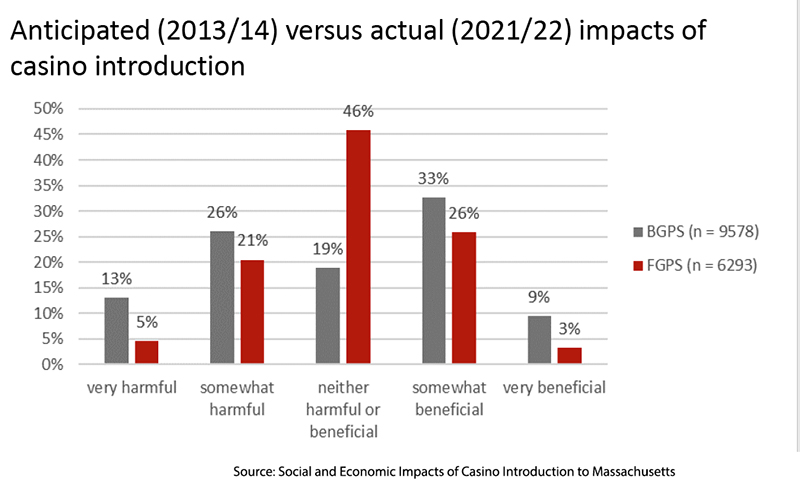

This graph, taken from the SEIGMA report, shows how the citizens in Massachusetts viewed the introduction of casino gambling before, in grey, and afterward, in red. It was a regression to the mean, with the extremes moving towards neither harmful nor beneficial.

The SEIGMA report shines a rather bleak spotlight on the reality of Massachusetts' casino experiment. Sure, there’s some tax revenue and a few jobs. Still, those benefits pale next to the unsettling reality that casinos bank on problem gamblers, who shoulder a staggering 90% of casino revenue. And yet, despite all this, Massachusetts residents have collectively shrugged, settling somewhere in the comfortable zone of indifference. Casinos, it seems, are neither our salvation nor our ruin—just another vice to tolerate, so long as the state can cash in.

[1] The report laments that about $360 million in Massachusetts’s citizens' gambling is spent in out-of-state venues.

[2] In Massachusetts, online sports betting is taxed at 20%, with the bulk going to the State’s general fund. According to one survey, “39% of men and 20% of women aged 18 to 49 bet on sporting events. Among young men, 38% say they’re betting more than they should, 19% have lied about the extent of their betting, and 18% have bet and lost money meant for meeting their financial obligations.”

[3] You need only to meet 4 of nine criteria: need to gamble more, unsuccessful attempts to control gambling, restlessness when cutting down, gambling as a way to escape, chasing losses, lying about gambling, jeopardizing or losing a job or relationship, reliance on others for money. You no longer have to commit illegal acts to qualify for the diagnosis.

Source: Social and Economic Impacts of Casino Introduction to Massachusetts Report to the Massachusetts Gaming Commission

A review of gambling disorder and substance use disorders Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation DOI: 10.2147/SAR.S83460