The FDA’s assault on vaping has yielded devastating consequences. Not only have millions of adults been denied legal access to low-risk vaping products they rely on to stay smoke-free, federal regulations are rapidly destroying thousands of jobs and billions of dollars worth of income, depriving ordinary Americans of their livelihoods.

The manifold problems begin with the FDA’s authorization process for e-cigarettes. Known as the Premarket Tobacco Application (PMTA) pathway, the agency’s regulatory approach is designed to ensure that a product appeals to adult smokers without enticing non-smokers, especially children.

It seems like a reasonable standard, but the PMTA pathway is a nightmare for applicants. Submitting an application to the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) can take years and cost millions of dollars; earning the agency’s authorization is nearly impossible. To date, manufacturers have submitted PMTAs for nearly seven million vaping products, and the FDA has authorized just 23 tobacco-flavored e-cigarette liquids and devices.

Evidence has emerged that FDA set artificially high standards after millions of PMTAs were submitted in 2020. Internal agency documents also revealed that CTP leadership overruled its scientific reviewers who were prepared to grant marketing authorization to some flavored vaping products.

Two federal appeals courts have chastised CTP for its flawed regulatory efforts on multiple occasions. “When courts look carefully at how the FDA has been considering these applications,” legal scholar Jonathan Adler has noted, “they discover an agency acting in an arbitrary and procedurally deficient fashion.” The US House Oversight Committee, which is currently investigating CTP, observes that the center’s erratic policies have “resulted in confusion, inefficiency, litigation, and suspicions of political interference.”

FDA crushes US small businesses

To get a ground-level view of how the FDA’s vaping prohibition has harmed American businesses and their employees, the American Vapor Manufacturers (AVM), of which I am vice president, recently interviewed Darrell Suriff, CEO of Pastel Cartel, a Texas-based company that sells the popular Esco Bar brand of disposable vapes.

Associated Press reporter Matthew Perrone featured a truncated version of Suriff’s story in a June article about the FDA’s attempted crackdown on illegally imported disposable vapes. Conspicuously missing from the AP report was any awareness of the FDA’s role in creating the black market it’s now desperately trying and failing to control. Perrone also paid no attention to the harm FDA has done to the independent vaping industry and its customers.

The anti-flavor crusade

In 2019, the Trump Administration announced plans to ban all flavored vaping products, excluding some disposables. This decision, Perrone wrote, enabled “under-the-radar importers and distributors” to begin flooding the US market with Chinese-made devices that are rapidly used and discarded by consumers. “Entrepreneurs can launch a new product by simply sending their logo and flavor requests to Chinese manufacturers, who promise to deliver tens of thousands of devices within weeks.”

The situation is much more complicated, however. The real problem wasn’t the disposable exemption but the flavor ban itself, which was orchestrated earlier by Mitch Zeller, the now-retired director of CTP. Zeller also presided over FDA’s scheme to ban more than six million vaping products in 2021.

CTP reported internally in March 2020 that 75 percent of adult users vape flavored products. Banning the myriad flavors these millions of people rely on guaranteed that a black market would sprout up to meet the demand. Perrone quoted an anti-nicotine activist who claimed the mass migration to disposables was proof that the vaping industry will innovate “around efforts to remove its youth-appealing products from the market.”

But that’s just false. Many disposable manufacturers were operating long before the FDA began blaming them for teen vaping. Suriff has been in business since 2011. Over those 12 years, his company has steadily opened additional retail locations, now totaling 30 stores sprawled across three states that have sold $400 million worth of disposables. However, his customers are adult smokers.

“We have the [sales] data from our retail stores. Customers have to give us their information and show an ID to buy a vape,” Suriff said. He’s never sold vaping products to children, and his employees know he has a zero-tolerance policy. “I don’t care how long you’ve worked for me. If you sell to a minor, you’re terminated immediately.”

It’s clear that these policies are working across the vaping industry. E-cigarette sales have exploded since 2014, but youth vaping in the US has halved since 2019; just 2.6 percent of American teens vape daily, and more than 90 percent have never tried vaping, according to the CDC. That necessarily means the widespread popularity of disposable vapes is driven by adult consumers.

Confiscated products

None of this seems to matter to the FDA. In May, the agency placed an import alert on several popular brands of disposable vapes, including Esco Bar. The order allows inspectors to confiscate the branded products as illegal tobacco imports until the shippers or manufacturers can prove they are lawfully in the US.

US Customs seized almost $14 million worth of products Suriff imported from his factory in China, then fined him $1.4 million for violating the ban. The only problem? The products were shipped before the import alert took effect. “We didn’t ship anything after the ban,” Suriff told AVM. “It was already in the air.”

A portion of the shipment was destined for an independent lab Suriff hired to perform some of the testing the FDA requires as part of a PMTA. Because of the import alert, the research firm rejected the shipment. Suriff expects to be charged an estimated $60,000 in storage fees for the confiscated product. The lab also charged him an additional $50,000 for delaying the study he hired them to conduct. The shipments were finally released after Suriff hired lawyers to navigate the Customs hurdles.

“They’re hitting us from every angle.”

The import confiscation was caused by another FDA misstep. In December 2022, the agency refused to accept (RTA) Suriff’s PMTA primarily because it lacked an updated form FDA began requiring just eight days earlier. The company Suriff hired to help file the application didn’t know about the change. “They rejected the application because the form was wrong,” Suriff said. “It contained the same data, but it was in a slightly different format.”

The FDA allows manufacturers to sell their products while regulators review their PMTAs. But the moment the agency issued an RTA, Suriff didn’t technically have an application on file at the FDA, which made shipping and selling Esco Bars illegal. “We’d been working to get everything done with a fine-tooth comb since December,” he explained. “We were two or three weeks away from [re-]submitting the full application, then FDA hit us with this [import ban].”

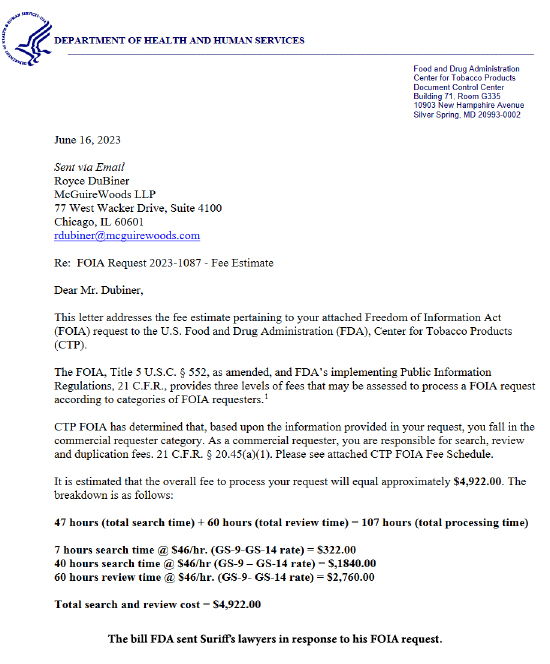

Suriff wanted more information about why the FDA rejected his first application, so he filed a Freedom of Information request (FOIA) to acquire any agency documents related to his PMTA. FDA agreed to send him the paperwork, but they wanted $5,000 to cover the cost of gathering the documents he asked for.

The expense of battling a giant federal bureaucracy has been staggering. Beyond all the fines and fees he’s paid thus far, Suriff estimates that he’s spent $1 million on lawyers this year alone to help him navigate all the regulatory pitfalls. Then there’s the severe damage to his company. As AVM reported recently, the import ban forced Pastel Cartel to close a 30,000-square-foot factory and lay off 500 of its 600 employees in China and 30 percent of its US workforce. “They’re hitting us from every angle,” Suriff said.

Black market flourishes

The most absurd part of the story, as Perrone reported, is that “Thousands of unauthorized vapes are pouring into the US” despite the FDA’s crackdown. The agency continues to boast that it “has taken swift action to curb the sale of illegal disposable e-cigarette products,” but the reality is that it targets Pastel Cartel and other compliant companies because they voluntarily submitted all the details about their operations as part of the PMTA process.

A factory employee in China samples illegal vaping products before they’re shipped to the US.Credit: Lindsey Stroud on Twitter.

The tobacco regulator hasn’t taken what may be the only sensible step. It could stop all imported vaping products at the border and then release the shipments that belong to companies that are submitting PMTAs.

Suriff has offered to help federal regulators with this task. He’s reported a dozen examples of websites illegally selling disposables through the FDA’s online portal; he’s called the agency 20 times asking to speak to someone involved in its enforcement and compliance efforts. At one point, Suriff tipped off the FDA about the location of illegal products that were imported as “USB chargers,” which allowed the manufacturer to avoid the 27.5% vape import tax.

After the agency ignored the tip, Suriff shared the same information with the FBI. The official he spoke with thanked him but said they weren’t sure who had jurisdiction to investigate the illegal shipments. “I never heard another word,” Suriff added.

Suriff’s experience illustrates what a mess the FDA has made of the US vaping market. Because the agency is systematically crushing manufacturers that tried to follow the rules, millions of Americans who rely on flavored disposables to remain smoke-free have been incentivized to take their chances with black-market vapes or just go back to smoking combustible cigarettes.

“They’re not going after companies that haven’t filed a PMTA,” Suriff concluded. “They’re making it harder for people like us who are spending millions trying to get this right.”

Editors Note: The American Council on Science and Health has been outspoken in our belief that vaping in the context of smoking is a helpful form of harm reduction. This article was written by Alli Boughner, vice president of the American Vapor Manufacturers, a trade group “formed to organize and represent small manufacturers as they navigate the federal regulatory process.” Publishing an article from “Industry” raises the same concerns about bias as placing industry representatives on government committees making regulatory decisions. But the problem for those committees is often that industry experts have the practical knowledge necessary to make effective policy. As we read this piece, it was clear that Ms. Boughner “brings to the table” information about regulatory actions that are not widely known. We bring this article to our readership in the spirit of full transparency, both to the author and her implicit bias and to how government agencies work “on our behalf.”