Everyone makes mistakes. Sometimes, it is easy to make the same mistake twice.

But, eight times? That's a different story.

A group of researchers have been caught publishing the same image in multiple papers and the retractions are starting to pile up.

According to a new story by the website retractionwatch.com, a retraction notice was published earlier this year in Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention (APJCP), that cites "duplicated contents" as the reason for the retraction.

So, how exactly does this happen? Scientists are not supposed to publish the same image twice. Scientific literature is designed to present new findings, in an effort to push the field forward. But, people do reuse figures, frequently with no incidence. Sometimes, it's a seemingly harmless control or model and someone could make an argument for the reasons why it should be allowed in certain circumstances. But, it is a slippery slope - like telling your child that they can skip their homework just this one time.

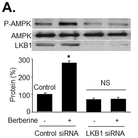

In the case of the APJCP paper, it was a Western blot - a technique done to measure the amount of protein expression. (1)

In this case, the problems with the paper were not limited to the images. Repeated text was found in the papers, as well. In fact, some of the papers have been found to be "almost identical."

With all of the times that this happens, why did this one get caught? It happened because journals want to uphold the scientific integrity of their own journal and the literature as a whole. And, they use email.

The papers were all published in the last few years. One of them, published in Korean Journal of Physiology (KJPP)—had been retracted in March of 2017. The editors-in-chief of KJPP emailed PLOS ONE and two other journals (Brain Injury and Experimental and Molecular Pathology) informing them of the misconduct with the images. When PLOS ONE started its retraction process for the paper submitted to them, they emailed APJCP. The retraction notice published by APJCP is, essentially, a copy of the email sent from PLOS ONE to their office.

But, it didn't actually start in the editors' offices. The first set of editors had been notified of the misconduct by a reader. And, it seems that this is where data policing needs to start. It is the scientists in the field who read every paper that is published on their topic. They know when they have seen something once or twice or eight times. In the absence of more advanced methods, it is up to the scientists to blow the whistle and elevate the quality of the scientific literature.

As an added layer of protection, more journals are implementing the use of software to check for reproduced text. For example, Elsevier has implemented the CrossCheck system where "All new submissions to many Elsevier journals are automatically screened using CrossCheck within the editorial system." However, because it only cross checks journals within that particular system, it has limitations. What is really needed for the scientific community as a whole is a universal system that could check the text (and images) across the board.

It is encouraging to know that the journals involved in this story, including PLOS ONE, the largest journal in the world which publishes between 20,000 - 30,000 articles each year, and handles many many more submissions, are going through the extra work to pursue these cases. They deserve a pat on the back, or eight, for the extra work that it took to pursue this case and retract the research from the literature. But, we also need more supports in place for identifying and dealing with these cases.

Notes:

(1) The duplicated figure.

Source: http://retractionwatch.com/2017/12/26/one-image-duplicated-eight-papers-...