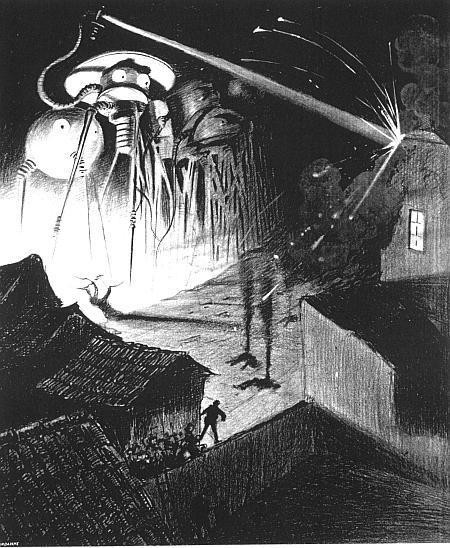

Some 80 years ago, the Mercury Radio Theater performed the War of the Worlds on the radio. The broadcast will be remembered for how it caused concern and even perhaps panic in Americans who thought they were tuning in to live radio rather than Orson Well’s radio drama. This episode is iconic of the power of stories and the engagement of radio; so remarkable that the same script was used again at least twice, in Ecuador and Buffalo, resulting in mobilization of Canada’s border protection services, the police, and in the case of Ecuador rioting and six deaths.

The performance has a backstory; there always is at least one to be found. The actors created verisimilitude for their play by drawing from the current cultural memes. The Hindenburg crash was a year earlier, and Mercury’s live on-scene reporter listened carefully to that other iconic radio broadcast to capture the cadence and tone of an eyewitness to a disaster – “Oh, the humanity!” Just over a month earlier Edward R. Murrow began radio reports of Europe’s growing crisis, introducing two new features to the radio. First, the idea of breaking in, “We interrupt this broadcast…” with “just can’t wait” news - an idea that proved so successful that it was immediately copied by many radio stations with interruptions piling one on top of another. Second, Murrow described disaster and chaos, not in the emotional tones of the Hindenburg's Herbert Morrison, but in a calm, controlled manner – more like FDR’s fireside chats.

Radio was then a new media, like Internet-driven social media is today. Orson Wells, a pioneer pushing the limits, an earlier version of social media “influencer.” Newspapers were losing the attention of their readers to radio, and some evidence suggests that the newspaper accounts of War of the World’s effect on the citizenry were to demonstrate radio’s danger, capable of causing untoward restlessness, anxiety and perhaps panic. Many years later, Orson Welles would suggest that the broadcast’s hidden message was a warning, to be careful of radio, it could fool you with “fake news.”

That warning might have been lost, but the tone of Edward R. Murrow, the cadence of Herbert Morrison, and the crabbing attention by “interrupting this broadcast” were not. They have been passed down, to another and another generation. We remain suckers for being fearful, even when there are little fears. Fear attracts our attention, and the resulting adrenaline rush is powerful. It is ironic that an 80-year old radio broadcast of a story of science fiction, itself now 120 years old, should be responsible for the science fiction that is often passed along as health and science news.

The mainstream reporting of health and science doesn’t give us an accurate picture, because science is more the daily grind of tiny steps than the "breakthroughs" we are shown. Fears, delivered in calm, soothing tones, are more effective in getting your attention. That is why there are so many crises, of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, internet addiction, lack of sleep. It is why one day you are told that salt is bad, and then it is good, and then it is “we don’t know.” Because fear sells and not just in media. It sells in the land of corporate influencers, like Big Pharma medicalizing small problems or Big Nature telling you of the latest Frankenfood, the work of greedy faceless others, tampering with genetics, and accelerating the apocalypse.

Source: I have shamelessly stolen the story and the concerns of a recent Radiolab podcast, War of the Worlds, by Jad Abumrad and Robert Krulwich. They are gems. If you are commuting to work, as 85% of the workforce does for an average of nearly 30 minutes a day, turn off live radio and turn on the podcasts. There are sports, politics, economics, science, advice to the love-lorn, everything you might desire presented with depth, not as sound bites. It contains the type of context, that Edward R. Murrow sought to provide, not infotainment and infomercials that have crowded out public conversation.