Doctors and scientists are throwing every conceivable size, shape, and color of the kitchen sink at COVID (as well they should) but there is little to show for it so far. Vaccines, antibodies, and convalescent plasma are still big unknowns. There is only one approved (1) direct-acting antiviral drug (remdesivir) and it has been thoroughly unimpressive in every trial. Other antivirals are still in the clinic, and while some of them should work, gambling on a drug without solid Phase 3 data behind it is reserved for suckers only.

A major portion of COVID research is aimed at finding drugs that would tame the immune system meltdown that makes this virus so deadly. Antiinflammatory steroids like dexamethasone seem to help. Last week Roche announced that Actemra, a drug for rheumatoid arthritis, seems to have some benefit in keeping very sick people off of ventilators. But the unvarnished truth is that we are only marginally better off than we were six months ago, even though potential treatments hit the news regularly.

Tinkering with the immune system is tricky; it's not difficult to go too far – wiping out its ability to fight the virus – or not far enough to impact the morbidity and mortality of the disease, as well as the body's ability to fight off other infections. Sort of like choosing between a fly swatter and a nuclear device to get rid of cockroaches.

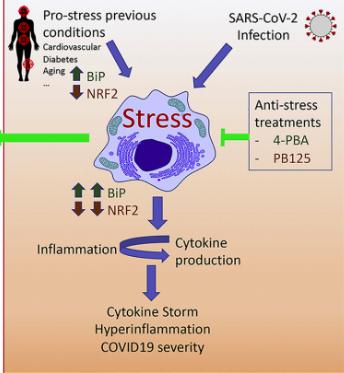

Ivan Duran, Ph.D., a professor at the University of Malaga, and colleagues suggest the possibility of something in between a fly swatter and a nuke in the latest issue of the journal Cytokine Growth Factor. He and his colleagues are focused on reducing cell stress. Duran, et. al., ask the question "Should we unstress SARS-CoV-2 infected cells?" (Emphasis mine)

"A possible solution to this impasse could be the use of precision medicine approaches searching for modulation of upstream regulators of the inflammatory response, as modulation would not mean a complete disruption of the inflammatory pathway but only control of the thresholds that lead to over-activation.

The one-million-dollar question is: what triggers the hyperinflammatory process during the virus infection? Cellular stress (including Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) stress, Oxidative Stress and mitochondrial stress) is a group of pathways that connects infection and inflammation and a potential candidate for such approach."

Duran, et. al., Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews, Volume 54, August 2020, Pages 3-5

A graphic of the cell biology behind the group's approach is shown in Figure 1(below).

Source: Duran, et. al., Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews, Volume 54, August 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.06.011

PHENYLBUTYRIC ACID AS A POTENTIAL TREATMENT - THE GOOD NEWS

The group is studying a common, inexpensive, and low toxicity repurposed drug called phenylbutyric aka PBA – a drug (brand name Buphenyl) that is already approved in the US for several rather obscure conditions. The drug has a lot going for it:

- Inexpensive (Sigma-Aldrich sells 100 grams for $161)

- Easy to make. Unlike remdesivir, which, according to ACSH advisor Dr. Katherine-Seley Radtke is "a bitch to make," PBA can be made in high yield/purity in one synthetic step from a wide variety of readily available chemicals.

- PBA is a pro-drug, not the active species. It is well-absorbed and readily metabolized to give phenylacetic acid, which does the work.

- PBA has been used in the US since the 1980s and has a pretty good side effect profile. The exception: about one-quarter of women who are menstruating develop menstrual dysfunction from the drug.

THE NOT-SO-GOOD NEWS

The evidence PBA might be effective against COVID is scant:

- The drug is effective in reducing inflammation associated with cardiovascular and lung disease, pancreatitis, liver failure... others.

- In a mouse model of respiratory deficiency, PBA protects fetal mice from death, although it is not known whether the protection is due to the reduction of inflammation. But this mouse model may or may not anything to do with the damage done by COVID. It is a very long stretch to assume that the authors have anything close to a validated animal model.

- The mechanism by which the 2002 SARS virus causes inflammation is consistent with that of the "new and improved" coronavirus, but this is little more than a theory. "Our results suggest that 4-PBA treatment could be used to prevent respiratory failure in COVID19 patients if the ER [Endoplasmic Reticulum] stress is confirmed to be part of the mechanism."

BOTTOM LINE

- The paper contains some nifty science, but much of it is based on little more than speculation and suggestion.

- If the authors' assumptions are correct, PBA could represent a major advance in COVID therapy. It would make a "good drug," based on its safety record, properties, and ease of obtaining material.

- But right now it's no more than a clever long shot. Perhaps a very long shot.

NOTE:

(1) Remdesivir isn't technically approved. It has been granted emergency use authorization by the FDA.