“Our goal was to estimate the effect of household exposure to handguns on nonowners' risk for dying by homicide.”

To answer that question, the researchers combined all of the registered voters in California, all registered gun owners, and the states’ mortality data from 2004 to 2016. They identified almost 600,000 individuals just starting to reside with a gun owner – 66% of these “cohabitants” were female, and 72% White, more lived in the suburbs or rural areas.

- 53% of the homicides occurred away from the victim's home, 38% in the home

- The spouse or intimate partner was responsible for 37% of those deaths, another family member 26%, a friend or acquaintance 21%, a stranger 16%, and the relationship was unknown for the remaining 26%.

- Firearms were used in half those at-home homicides, 77% of those away from home.

- Cohabitants had no difference in all-cause mortality whether their companion was a handgun owner or not.

“Cohabitants of handgun owners were more than twice as likely to die by homicide as neighbors living in gun-free homes. This elevated risk was chiefly attributable to higher rates of homicide by firearm. Cohabitants of handgun owners, two thirds of whom were women, faced especially high risks for homicide at home at the hands of spouses and intimate partners. A small minority of homicides involved victims killed by strangers at home; cohabitants of handgun owners did not experience such fatal attacks at lower rates than their neighbors in gun-free homes.”

Two of the study’s limitations are worth noting. First, they could not attribute these deaths to the actual handgun owner or the owned gun. Second, these cohabitants had a higher non-firearm homicide rate, but it was not statistically significant. But as the writer of the accompanying editorial wrote, “these findings suggest that living with a handgun owner does not seem to offer protection from homicide for adults.”

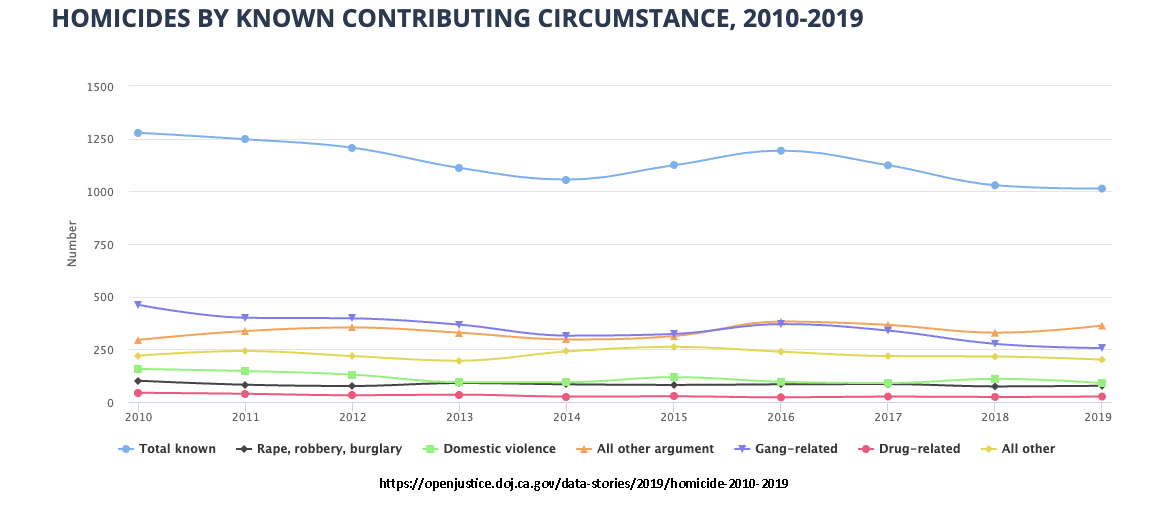

Let's begin with some more data on California’s homicides to bring context.

Firearms are the weapon of choice in homicides

Homicides more frequently involve people we know

The homicide of a cohabitant in their home is arguably a form of extreme domestic violence. Domestic violence resulting in homicide is real and remained relatively constant until the pandemic

The study gets at a fundamental problem in gun research – you will understand the problem from the memes. Do guns kill people, or do people kill people? Put in more academic terms,

“[Does] the presence of firearms independently [make] violent situations more lethal, known as an instrumentality effect, or [will] determined offenders ... simply substitute other weapons to affect fatalities in the absence of guns?”

Could it be that we should be saying, “People without guns injure people; guns kill them?”

Prior research on intimate and family assaults suggested that firearms were three-fold more likely to end in death than the use of knives; and 23 times more likely to result in death than the use of other weapons – bodily force. In a study from California’s Department of Justice of 1.6 million 911 calls for domestic violence incidents in a similar time frame, 57% involved no weapons, 34% involved physical force. Only a tiny fraction, 0.7%, involved firearms.

To use an epidemiologic term, the case-fatality rate with firearms is roughly 20%, and it is far lower, 7-fold for knives and even less so for beating on someone. As this second group of researchers concludes,

“the dangerousness of the instrument used in violent attacks plays a critical role in producing fatal outcomes.”

As they are for suicides, firearms are very effective at taking lives. Reducing the number of guns available remains problematic. Given these two studies, it now makes sense, at least for me, to ask for consent from a spouse or cohabitant to have a gun in the home.

Source: Homicide Deaths Among Adult Cohabitants of Handgun Owners in California, 2004 to 2016 - A Cohort Study Annals of Internal Medicine DOI: 10.7326/M21-3762

Firearm Instrumentality: Do Guns Make Violent Situations More Lethal? Annual Review of Criminology DOI: 10.1146/annurev-criminol-061020-021528