A decade or so ago, I got to take a tour of one of the Federal Reserve banks; in the vault, there was a massive brass balance that our guide told us could weigh up to 600 pounds of gold (or anything else) to a precision of the weight of a single dollar bill (about 1 gram). We were dubious – until they demonstrated by putting a single dollar bill on one side of the empty balance, and we watched the needle deflect. Under the right conditions, a single gram could tip the balance on 600 pounds of gold; under the right conditions, a slight nudge can cause a disproportionate movement.

The latest issue of the prestigious scientific journal Science contains a fascinating paper by Emily Judd, a scientist at the Smithsonian Institution, and six coauthors; what they report is the result of their efforts to determine how the Earth’s average temperature has changed over nearly a half-billion years – virtually the entire history of complex life on our planet – using scientific and calculational techniques that are more robust and that rely on more hard data than previous efforts. First, let me tell you what they found and then some of what I think some of it might mean.

- One of the more surprising things is that, over this entire period, the average global temperature today (about 57° F) is unusually low; there have only been two times when temperatures have been lower than today, and one of those intervals was relatively brief.

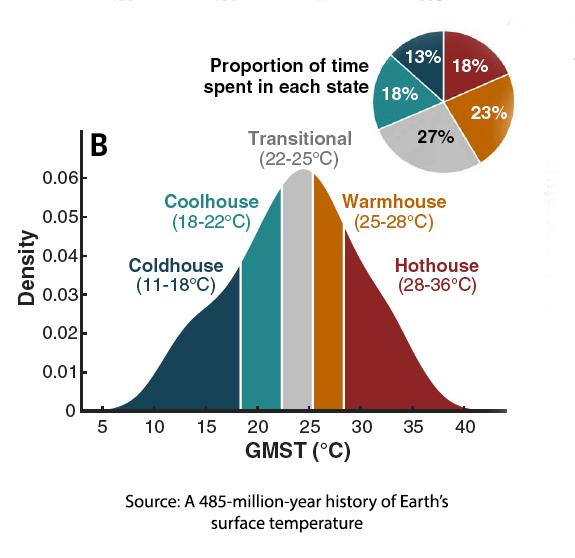

- Over this time, the average global temperature has varied from about 52-97° F, with 31% of that interval spent in cold (52-46°F) and cool (46-72°F) conditions, 41% of the time, and 41% of the time in warm (77-82°F) or hot (82-97°F) conditions. The remaining 27% of the time was spent transitioning between warm/hot and cool/cold or back (72-77°F).

Thus, today’s average temperature puts Earth squarely in the cold category

The authors note that there are at least two mass extinctions associated with dramatic short-term changes in global temperatures:

- At the end of the Ordovician (about 440 million years ago), temperatures plunged by 7° C in just a few million years, launching a brief ice age [1]

- At the end of the Permian, 250 million years ago, global temperatures spiked by about 12° C in less than a million years, possibly contributing to the worst mass extinction in Earth’s history.

- The other three mass extinctions are only loosely correlated with lesser temperature changes. Two other large and abrupt temperature increases don’t appear to correlate with mass extinction.

Two things jump out to me. First, our planet is usually significantly warmer than even the worst-case global warming scenarios (a 3°C increase in global temperatures will bring us to about 62 °F, still in this paper’s “cold” category). This suggests our planet can end up far warmer than our current projections indicate.

Second, at least four times, the temperature turned on a dime, shooting up or down substantially in a short period of time. Just as a single dollar bill can tip the scales on 600 pounds of gold, so, too, might a relatively minor change in any of several parameters – the amount of greenhouse gas in our atmosphere, the Sun’s energy output, the amount of ice in the Arctic Ocean, the amount of water flowing through the Gulf Stream, or any of many other things – might take us just past that tipping point, launching Earth into a hothouse that would make the hot summers of the last few years seem like a brisk Autumn day, or that could trigger a new ice age.

Here’s the thing – we don’t know which parameter(s) might be the trigger or how close to the tipping point we might be. To me, that’s the take-home message, and that’s what ought to give us all pause.

[1] As a side note, just to make things more interesting, an astrophysicist named Adrian Melott has found evidence that a nearby gamma-ray burst might have triggered the Ordovician extinction

Source: A 485-million-year history of Earth’s surface temperature Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adk3705