There is a LOT of misinformation when it comes to our foods, especially how our foods are grown and the farming technologies used. Ironically, much of it is spread by people who claim they want healthy food yet propagate harmful lies about our food supply, especially organic and conventional farming. Unfortunately, anti-science activists, including the Environmental Working Group, Greenpeace, Consumer Reports, RFK Jr., and Vani Hari (“Food Babe”), have made a lot of money demonizing perfectly safe, nutritious, and beneficial food crops for their personal benefit.

This rhetoric has been deeply entrenched in society for decades, which means people of ALL ideologies have fallen prey to misinformation about pesticides and “chemicals.” Let’s do some fact-checking.

Chemophobia And The “Appeal To Nature Fallacy”

Almost every time anyone with expertise tries to discuss the nuance between organic and conventional foods - topics get conflated. Organic and conventional describe agricultural practices, such as farming methods and technologies, but not in this context, different chemistries.

The organic farming industry grew legs as chemophobia spread among the public because of conflation with legitimate chemical issues, like the Love Canal incident, with “chemicals” as broadly defined. What grew from these instances was fear and demonization of synthetic chemicals, facilitated by the appeal to nature fallacy, when someone assumes something is good because it's natural or bad because it's unnatural. This coincided with the “medical freedom” movement (a way to wrap up the anti-vaccine and wellness movement in a less offensive bow) and the removal of FDA oversight on dietary supplements.

There is a major difference between large-scale exposures to various chemicals, including industrial spills, and trace exposures when the same chemicals are not misused. This is a persistent misconception, and it has been leveraged to spread fear and disinformation.

Organic Certifications And The National Organic Program Are Ideological, Not Scientific.

The National Organic Program (NOP), established by the passage of the US Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 (OFPA), is a program managed by the USDA that sets standards for what qualifies as organic farming, the rules and criteria for what farming and growing practices qualify a farm for the USDA Organic certification. That’s it. It does not mean practices are better, safer, more eco-friendly, more nutritious, or pesticide-free. (There is an extensive list of permitted pesticides and fertilizers for organic farming.)

The 1990 OFPA and NOP were lobbied for by farmers and organizations, like the Rodale Institute and the Organic Trade Association (OTA), who wanted to legitimize their farming methods, promote them to the public, and increase profits. Remember, organic farming practices are only 5-13% more expensive but are 22-35% more profitable than conventional farming. It is lucrative, but it is also not driven by scientific evidence.

Organic certification has criteria for:

- Allowed and prohibited substances (e.g., pesticides and fertilizers).

- Farming practices (e.g., tilling methods)

- Livestock management (e.g., organic feed, no antibiotics for sick animals, no synthetic hormones) must be provided.

- Processing (e.g., GMOs are prohibited in organic farming)

However, Organic certification has NO criteria for safety or nutrition.

The NOP centers around personal beliefs and perceived values, often focusing on “natural” substances perceived by consumers as “clean,” which mislead consumers using clever marketing ploys. As a result, people believe that organic is superior, uses fewer chemicals, leads to improved products, and is safer.

Unfortunately, that isn’t true. Many modern synthetic pesticides have taken natural chemicals (that are used as organic pesticides) and improved upon them using science to reduce environmental harm, off-target effects, and overall safety.

Organic pesticides are not as rigorously monitored and regulated as conventional pesticides

The NOP is a certification that grants farms the "USDA Organic" label but also creates a false perception that organic is "pesticide-free" or safer. But all it means is that organic-approved pesticides are “natural” chemicals - yet the source of a chemical has no bearing on its potential harm or safety. There are plenty of natural chemicals that can be harmful at low exposures (read about fungicides used in organic versus conventional farming for a key example here).

In contrast, pesticides used in conventional farming that are synthetic chemicals are regulated by the EPA and require extensive data on toxicity, environmental impact, and efficacy before approval. The USDA also manages the Pesticide Data Program (PDP), which publishes an annual residue report. The PDP is a monitoring program that assesses trace residuals of synthetic pesticides used in conventional farming. It was created in 1991 because of public outcry and misinformation about synthetic versus natural pesticides.

The false belief that “natural chemicals” are inherently safe and chemophobia aimed at synthetic chemicals means the USDA PDP residue report only includes synthetic pesticide residues used in conventional farming; organic pesticides are excluded from this regulatory oversight. Weird, right?

Residual Synthetic Pesticides On Food Items

Residue levels are monitored and reported, and every year, the report demonstrates the safety of conventionally-grown produce. The residue levels tested for and reported are not levels that should concern you. If anything, the USDA’s annual Pesticide Data Program (PDP) report should give you confidence that not only are farmers using as little pesticide application as possible to grow your foods and post-harvest processing of crops reduces any trace levels to minuscule quantities. Every year, over 99% of tested samples are below safety thresholds for each pesticide in question. Last year’s report demonstrates the same. Not only did over 99% of samples tested meet all safety criteria, but 38.8% of the thousands of samples monitored had no detectable pesticide residues.

Consider this example.

Malathion is a broad-spectrum insecticide used to control many crop pests and insects that can cause vector-borne diseases in animals and humans (like mosquitoes, flies, and ticks).

In farming, it is primarily used to control pests like aphids, thrips, leafhoppers, whiteflies, cucumber beetles, and grasshoppers. It also controls stored grain pests like weevils and grain beetles. Not only do these insects directly damage food crops, but many of them are vectors for plant diseases - they can also transmit viruses that can harm plants or facilitate the growth of fungal pathogens that harm plants.

Obviously, it is important to control these insects that threaten our food supplies.

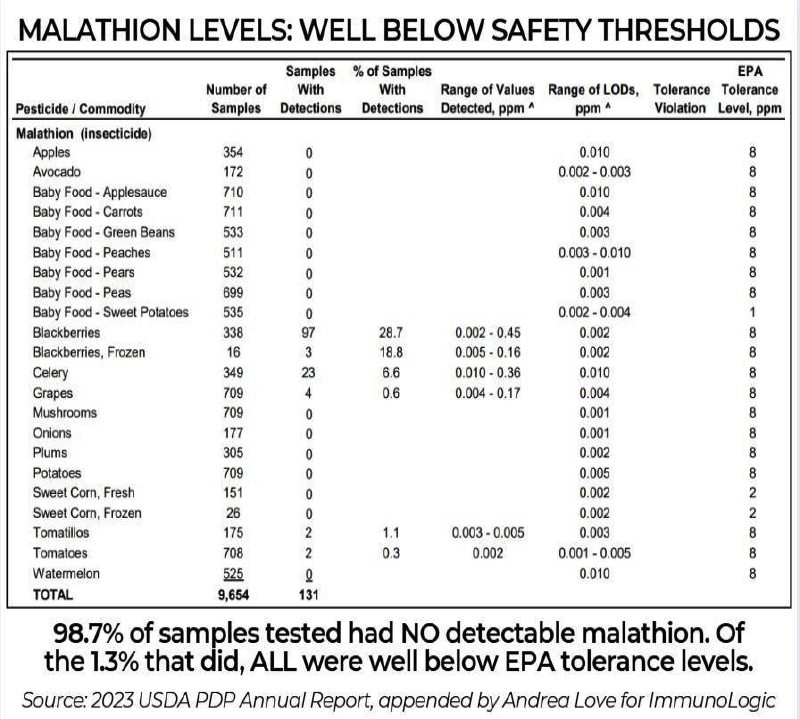

In last year’s PDP, using highly sensitive analytical chemistry methods assessing levels in the parts per million to parts per trillion [1], malathion was detected in 1.3% of all samples. (Detection doesn’t equal relevance, but we will get to that.) Of the samples with detected malathion levels, all were below the EPA tolerance level for that food (for the ones in question, the tolerance is 8 ppm). In fact, the maximum level of malathion detected in ANY sample was 0.45 ppm, which is nearly 18 times lower than the tolerance threshold.

Do you need to be concerned about these detections?

NO.

Consider a hypothetical. Say you see the EWG’s Dirty Dozen list and their claim blackberries are “dirty” according to their wildly misleading and anti-science methods. How many blackberries would you need to eat to even pose a risk?

In this instance, you have to convert the pesticide tolerance level to the acceptable daily intake (ADI), the amount of a substance that a human could ingest every day for their entire life and experience no adverse effects. The ADI level for malathion, set by the World Health Organization is 0.3 mg/kg/day. [2]

A person weighing 70 kg (154 lbs) would have to ingest 21 milligrams of malathion daily to reach the ADI. If we eat blackberries with the highest level detected at 0.45 ppm (0.45 milligrams of malathion per 1,000 grams (kg) of blackberries), that 70 kg individual would need to eat 46.7 kilograms, over 90 pounds of blackberries daily to reach malathion’s ADI.

Can you see why this is not a concern?

Detection Doesn’t Equal Harm.

Every chemical has a toxicity threshold dependent on dose, even water.

Pesticides might be detected in food, but that means the most sensitive analytical chemistry tools can find them. We can detect levels of substances that are irrelevant to our health, measured in units like parts per million, parts per billion, or parts per trillion. We have to compare those detected levels to their potential risk and your potential exposure.

This is a fundamental challenge when discussing pesticides or, really, any chemical (even though everything is chemicals).

The challenge is made worse when groups like the EWG take these minuscule quantities of detected pesticides and manipulate them to scare people from perfectly safe and more affordable conventional foods (read their methods here).

Of course, EWG is funded by large organic farming industry partners, so they have an obvious profit motive to drive consumers to spend more money on products that are less regulated and offer no benefit. That doesn’t even mention that many organic pesticides can be more damaging to the environment than conventional options, as organic farming has a lower yield per area of land. Organic is a marketing-related certification more than anything.

What’s particularly funny about the EWG’s Dirty Dozen list is their schtick aims to undermine safety agencies yet they use (misuse actually) USDA data to scare people! So, I guess you can’t trust the safety agencies unless you manipulate their data to spread disinformation.

The TL;DR?

- Conventionally grown food items are safe and nutritious, and their farming methods and pest control practices are regulated, monitored, and reported to the public.

- Demonizing affordable and nutritious conventional produce is the harmful thing, not the trace levels of pesticides on them.

The false dichotomy between conventional and organic isn't just misleading; it's dangerous. Our constant attention to natural versus synthetic creates fear and distrust when, in actuality, our food has never been safer.

We should be more concerned about ensuring everyone, including those of lower income, are assured of the nutrition and safety of all fresh foods. Only about 12% of Americans follow our national fruit and vegetable consumption guidelines. Negative messaging about the purported harms of “pesticides” on foods causes lower-income individuals to purchase and consume fewer fruits and vegetables. Underconsumption of produce items high in nutrients and fiber poses a legitimate risk to many aspects of our health. While much of that results from food equity and social determinants of health, a major exacerbating factor is harmful disinformation about the safety of more affordable produce.

If you want to improve access to and consumption of healthy foods, stop spreading lies about conventional farming.

[1] For context, a part per million is like 1 second in 11.6 days, a part per billion is 1 second in 31.7 years, and a part per trillion is 1 second in 31,700 years.

[2] The WHO level uses a “fudge factor” of 100 based on the No-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level (NOAEL) determined by toxicology studies to set their ADI – making the ADI level 100 times lower than any level that led to any adverse effect in a comprehensive array of studies.