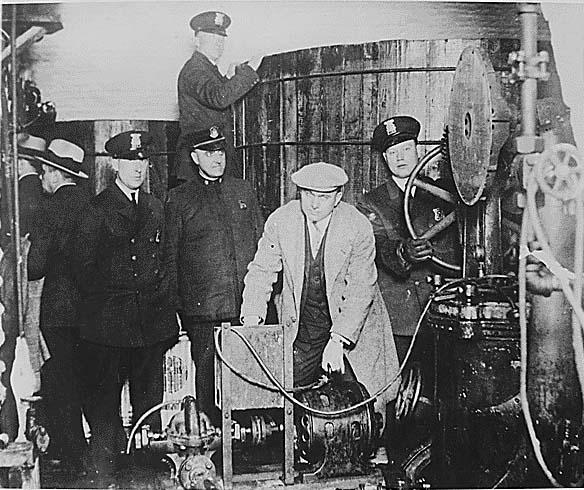

If you remember your high-school US history class, you know that prohibition was an abject failure. Alcohol consumption declined sharply in the early 1920s only to spike over the next several years, accompanied by a massive black market and increasing gang violence. The takeaway from this lesson is pretty clear: laws are not magic spells; writing words on a piece of paper doesn't necessarily incentivize people to change their behavior.

The same phenomenon is at work in several countries that restrict farmer access to genetically engineered (GE) crops. Fortunately, no Al Capone copycats are killing rival gangsters over the right to sell biotech seeds today, but there is a black market for the technology, and many farmers openly take advantage of it.

Breaking the law should always be frowned upon, of course, but these rebellious growers are powerful witnesses to the fact that opposition to crop biotechnology is almost always political—literally, it's politicians and lobbyists who keep the restrictions in place. Scientific evidence and the interests of farmers are rarely the motivating factors in these cases. Let's look at a few examples.

Indian cotton farmers: let them arrest us!

We begin our world tour in India. Strictly speaking, growing GE crops isn't illegal there; over 95% of the country's cotton is grown from insect-resistant (Bt) plants. Indian researchers have developed other engineered crops that benefit farmers and consumers, notably high-yield mustard and Bt eggplant. And India's cotton farmers are eager to grow varieties that are both insect- and herbicide-resistant. Crops with these “stacked” traits are enormously useful to growers who are up against yield-killing pests, but regulators who have the authority to approve these and other GE crops simply won't.

According to a recent study, India is stuck at this impasse largely because the institutions that develop and promote biotech crops aren't “appropriately linked” with those that regulate said crops. The result, the researchers noted, is that.

even after extensive debate and creation of new institutions, there is a persisting situation of antagonism and low public trust in GM technology as a viable solution for India’s agricultural problems. This has impeded the innovation and translation process despite successful field trials of many indigenous GM crop.

Many farmers in the country have reacted to this situation with predictable frustration. Beginning in 2019, for example, a group of cotton growers organized protests during which they very publicly planted the herbicide-tolerant, insect-resistant varieties they've been denied legal access to. When the state ordered them to stop, they doubled down: “Let the government arrest us!”

“Our borders are porous:” GE crops from Kenya find their way to Uganda.

Uganda has spent years and many millions of dollars developing crop biotech expertise. Despite this substantial public investment, the country has failed multiple times since 2004 to enact regulations that would allow farmers to cultivate GE crops. Recognizing the need for a law, the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) is drafting a “stop-gap measure” to give farmers guidance until the country's parliament passes permanent legislation.

NEMA's effort is motivated by a simple observation: “Our borders are porous, what is in Kenya, will find its way into Uganda.” Dr. James Kasigwa, director of biosafety at the Ministry of Science Technology and Innovations, observed last July. Farmers have said the same thing. One anonymous Cassava grower told the Genetic Literacy Project in June 2020:

Farmers living in border districts of these countries have no problem sharing seed; we have been doing this over time. I am aware that the GM cassava varieties are resistant to [cassava brown streak virus], which is a challenge to a number of farmers growing the plant. Usually when I plant resistant varieties, I am able to harvest two tons per hectare. But when the disease causes rotting, I can hardly harvest anything from the farm.

Peru's not-so-effective moratorium

Although America's anti-GMO movement has lost significant influence in recent years, the same can't be said of activist groups in other countries. In Peru, the local science community was engaged in a ferocious PR battle with organic food lobbyists who want to maintain the country's status as an “ancestral homeland to organic food produced from native seeds." In January, the country extended its ban on GE crop cultivation for 15 years.

Peru as an ancestral homeland to organic food is little more than a marketing myth, though. The country has avidly imported GE corn and soy for many years. In 2018 and 2019 alone, Peru imported 3.7 million metric tons of corn from the US, the vast majority of which is genetically engineered. Going back to at least 2009, farmers across Peru have repurposed imported, insect-resistant corn by crossing it with a local variety known as “Pato,” typically used as animal feed. How and why this began is unclear, but growers noticed pretty quickly that their crops were less vulnerable to pest attack, so they kept growing this souped-up corn. [1]

The most interesting part of the story: biotech companies, regulators, and anti-GMO groups all know this goes on and nobody wants to address it. The firms don't want to be associated with anything illegal; Peruvian regulators don't want to deal with incendiary political issues, and the anti-biotech movement doesn't want to give up their marketing narrative.

What better evidence could there be for the safety and efficacy of GE crops?

[1] The corn actually contains an older insect-resistance trait Monsanto released in the 1990s. If given access to newer crop varieties, farmers would probably see even greater results.